Guardians of the Nation’s Glory: The Civil War Memorials of Northwest Washington, D.C.

ECW welcomes guest author Kyle R. Hallowell

Introduction

When most people think of the location of Civil War memorials, they are likely to think of places such as Gettysburg or Antietam, not Washington, D.C., which is famous for its memorials to Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln. However, many may be surprised to learn that Washington and Northwest Washington, especially, are densely landscaped with memorials commemorating the Civil War. In President James A. Garfield’s words, these memorials are “permanent guardians of the nation’s glory” and must be a stop on any Civil War enthusiast’s travel itinerary. Below is a list of memorials I recommend visiting and some interesting facts about them. This list is in no way exhaustive and only highlights a few of the more noteworthy statues in Washington.

Memorials

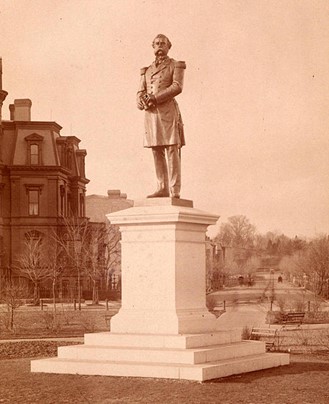

Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, Scott Circle

Winfield Scott was the first Civil War general memorialized with a bronze statue in postwar Washington. In 1867, Congress allocated $35,000 to erect a memorial to Scott. The commission went to New York sculptor Henry Kirke Brown, who was widely praised for his 1856 statue of George Washington. Brown’s sculpture was complete by 1872, and when it came time for casting, the federal government contributed cannons used during the Mexican-American War. The statue’s base was carved from a single piece of granite, which at the time was the largest stone ever successfully quarried in America.[1] Scott’s memorial was unveiled without a ceremony in 1874 and immediately drew criticism. Many observers thought Scott was depicted as too fat, old, and stiff, with one critic saying that Scott looked like an old sack of flour. Scott’s horse drew even worse criticism, with many observers saying it looked light, delicate, thin, timid, and dreadfully proportioned. Philip Sheridan, who lived a few blocks away from the memorial, is said to have begged his wife never to let him be immortalized on such a dreadful animal.[2]

Brigadier General James B. McPherson, McPherson Square

James B. McPherson was beloved by his soldiers and his superiors alike. His death outside Atlanta on July 22, 1864 made McPherson a martyr to the Union cause and endowed the soldiers of the Army of the Tennessee with a desire to commemorate him. In one of their first post-war meetings, the men of the Society of the Army of the Tennessee voted to honor McPherson with a statue in Washington. It would be the first of the many bronze Civil War statues commissioned by a veterans’ group.[3] The society raised $23,500 for the statue, and Congress donated cannons captured in the Atlanta campaign to be melted down.[4] After an aborted first attempt by another artist, the society chose Cincinnati sculptor Louis Rebisso to produce the McPherson statue. Initially, the design for the memorial included a vault for McPherson’s body, but before it could be exhumed, a group in McPherson’s birthplace, Clyde, Ohio, filed an injunction to prevent the exhumation. McPherson’s statue was unveiled on October 18, 1876. The ceremony was presided over by William T. Sherman, and John A. Logan gave the chief address. The unveiling ceremony was preceded by a parade of Union veterans and political dignitaries, establishing the precedent for more than a dozen future ceremonies.

Major General George H. Thomas, Thomas Circle

Soon after Thomas died in 1870, the Society of the Army of the Cumberland decided to memorialize their former commander. By 1873, they had raised $10,000 and asked Congress for additional funds and the necessary cannons to make the statue. Congress provided 88 cannons captured during the Atlanta campaign and appropriated $25,000 for the statue’s pedestal. John Quincy Adams Ward was awarded the commission for the statue and, in close consultation with Mrs. Thomas, had the plaster cast finished by 1879. On November 19, 1879, the memorial to Thomas was dedicated in an imposing ceremony that, according to Harper’s Weekly, was “the grandest ever witnessed at the national capitol since the grand review of the victorious Union Armies in 1865.”[5] The ceremony was so well attended that the parade, consisting of G.A.R. members, veterans, soldiers, and various bands, stretched for two miles. General Don Carlos Buell did the unveiling, and President Rutherford B. Hayes accepted the statue on behalf of the American people.[6] Critics consider the Thomas Memorial one of the finest equestrian statues in Washington.

Admiral David Farragut, Farragut Square

A mere two blocks from the White House, in the square named for him, stands the twenty-foot-tall memorial to the U.S. Navy’s first admiral, David G. Farragut. He was the first American naval officer to be honored this way.[7] Farragut’s memorial is unique because, unlike statues of famous generals that are typically cast in bronze from captured cannons, Farragut’s is cast from the propeller of his flagship, the USS Hartford.[8] The effort to memorialize Farragut began shortly after his death in August 1870. That winter, another notable Union veteran, Nathaniel P. Banks, serving as a congressman, introduced a resolution calling for a public monument to Farragut. The resolution passed, and by January187 3, thirteen models had been submitted for consideration. After much behind-the-scenes wrangling, a three-person committee, consisting of Farragut’s widow, William T. Sherman, and Secretary of the Navy George Robeson, was appointed to make the final selection. The committee chose the sculpture submitted by Ms. Vinnie Ream, who was already famous for being the first female artist to receive a government commission at age 19.[9] Ream was awarded the $20,000 commission and produced a plaster sculpture for casting over the next two years. The memorial’s unveiling was initially scheduled on President Garfield’s inauguration day, but fate intervened, and the ceremony had to be postponed to April 25, 1881, coinciding with the anniversary of Farragut’s victory at New Orleans. At the unveiling, two former members of Hartford’s crew and veterans of the battle of Mobile Bay, Quartermaster Knowles and Boatswain James Wiley, hoisted the flag that covered the statue, drawing immense applause.[10] President Garfield then made a brief speech and accepted the statue on behalf of the American people.

Major General John A. Logan, Logan Circle

The Logan Statue was the second equestrian monument in Washington commissioned by the Army of the Tennessee. Logan was perhaps the most successful of the “political generals” during the war and was highly regarded by his soldiers and superiors. After the war, he served in Congress for two decades and was the Republican vice-presidential candidate in 1884. In office, Logan was an outspoken advocate for soldiers and founded the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). Following his death in 1886, the G.A.R., in partnership with Logan’s widow and the Society of the Army of Tennessee, persuaded Congress to appoint a commission to select a sculptor and site for a statue of Logan. Years later, the commission members had made their selection. They chose the Rome-based American artist Franklin Simmons, to whom they paid $65,000 for the work.[11] Simmons completed the statue and pedestal in 1901, whereupon it was shipped to America. The Logan statue was erected in Iowa Circle, later renamed Logan Circle, and was dedicated on April 9, 1901, with President William McKinley accepting the statue. A parade preceded the ceremony, and the unveiling was performed by one of Logan’s grandsons. While the statue of Logan has been well regarded, the pedestal, containing relief panels of his life, has met with criticism since it depicts events that never occurred. Specifically, it depicts Logan being sworn into the Senate in 1879 by Vice President Chester A. Arthur, who did not enter the vice presidency until 1881. Mrs. Logan inspired this depiction, who later stated that the scene was “patriotic and moving” and that reproducing the real scene would have been “absurd.”[12]

Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont Memorial Fountain, Du Pont Circle

In 1865, two years after being relieved of command due to his failure to take Charleston, Samuel F. Du Pont died. His widow, Sophie, who was also his first cousin, sought to repair the admiral’s tarnished reputation by having a memorial of him erected. She lobbied Congress, which authorized $20,000 for a memorial. The sculptor Launt Thompson was chosen, and the statue was finished in seven months. The Du Pont statue was dedicated in December 1884 and was almost immediately criticized for its bland depiction of Du Pont. By 1909, the pedestal had started to crumble, causing Du Pont to list, which prompted many jokes about his sobriety. Embarrassed at the disrepair, the Du Pont family, in conjunction with Congress, had the statue removed. They then hired Daniel C. French, the sculptor of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial, to design a fountain for the admiral. At the cost of $77,521, French began work in 1918 and had the fountain dedicated in 1921.[13]

Memorial Locations

Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, Scott Circle

Admiral David Farragut, Farragut Square

Brigadier General James Birdseye McPherson, McPherson Square

Major General George H. Thomas, Thomas Circle

Admiral David Farragut, Farragut Square

Major General John A. Logan, Logan Circle

Rear Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont Memorial Fountain, Du Pont Circle

Kyle R. Hallowell is an active-duty US Army Strategist currently studying International Policy at Texas A&M University. He has a BA in History from Norwich University and has been passionate about the Civil War since childhood. He lives in Northern Virginia with his wife and son.

Bibliography

“Farragut.” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), April 25, 1881 1881, 1,5,8. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83045462/1881-04-25/ed-1/?sp=1&st=text&r=0.452,-0.006,0.501,0.436,0.

Jacob, Kathryn Allamong. Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

“The Statue of General Thomas.” Harper’s Weekly, December 6, 1879, 959. https://archive.org/details/sim_harpers-weekly_harpers-weekly_1879-12-06_23_1197/page/958/mode/2up.

[1] Kathryn Allamong Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C. (Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 100.

[2] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 101.

[3] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 89.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “The Statue of General Thomas,” Harper’s Weekly, December 6, 1879, https://archive.org/details/sim_harpers-weekly_harpers-weekly_1879-12-06_23_1197/page/958/mode/2up.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Farragut,” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), April 25, 1881 1881, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83045462/1881-04-25/ed-1/?sp=1&st=text&r=0.452,-0.006,0.501,0.436,0.

[8] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 107-09.

[9] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 102.

[10] “Farragut.”

[11] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 83.

[12] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 84.

[13] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 130.

What a fun read! Thanks for sharing

Thanks Evan! I am glad that you enjoyed it.

thanks Kyle for this great post — had no idea that Du Pont circle once had a Du Pont statue … poor RADM Du Pont can’t get a break: gets fired over Charleston, then his statue gets fired … and i thought General Scott looked positively svelte given his 300 lb. girth in 1861.

I am glad that you enjoyed it Sir!

Kyle — Thanks for a very interesting post. Now you will have to do part 2 for northwest to include McClellan on Ct. Ave., Sheridan on Mass. Ave., Nuns of the Battlefield on Rhode Island Ave., and GAR Memorial.

Thanks John! I am glad that you enjoyed it. A part II will be in the works soon. However, it will include those memorials and some other interesting sights, such as the National Building Museum.

Nice post, my favorites are

Hancock the Superb – Pennsylvania & 7th by the Navy Archives metro station.

Meade Memorial – 300ish Constitution Ave

And if someone is traveling to see these, budget time for visiting Arlington Cemetery

Thank you Henry! My favorites are the memorials of Thomas and Farragut.