Weaponizing Children’s Education During the U.S. Civil War

There has been significant political discourse in recent years regarding using education as a political weapon. This is not new, as even during the U.S. Civil War, battles were waged in government halls and classrooms over curriculum and education of youths.

Confederate schools suffered for want of wartime teachers, as rebel armies mobilized virtually all Anglo men within their borders. Initial Confederate conscription policies exempted teachers. Because of this, schools “sprung up in abundance” led by men wishing to avoid military service who were often “no more fit for teachers than they are for Generals.”[1] Newspapers demanded women fill positions, with one boasting “ladies can teach, and will do it, if they can thereby relieve able-bodied men and let them go into the army.”[2] In 1863, North Carolina estimated 139 men would have been conscripted if not for their teaching position.[3] Because of wartime needs, by 1864 teacher exemptions disappeared, and schools turned to women or men who were “not subject to conscription” to lead classrooms.[4]

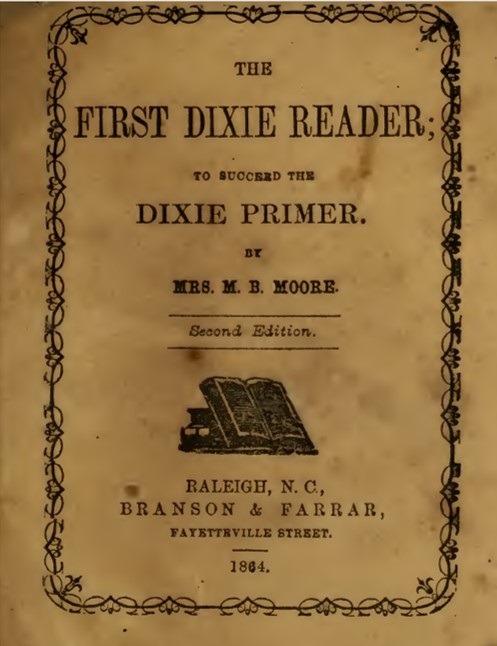

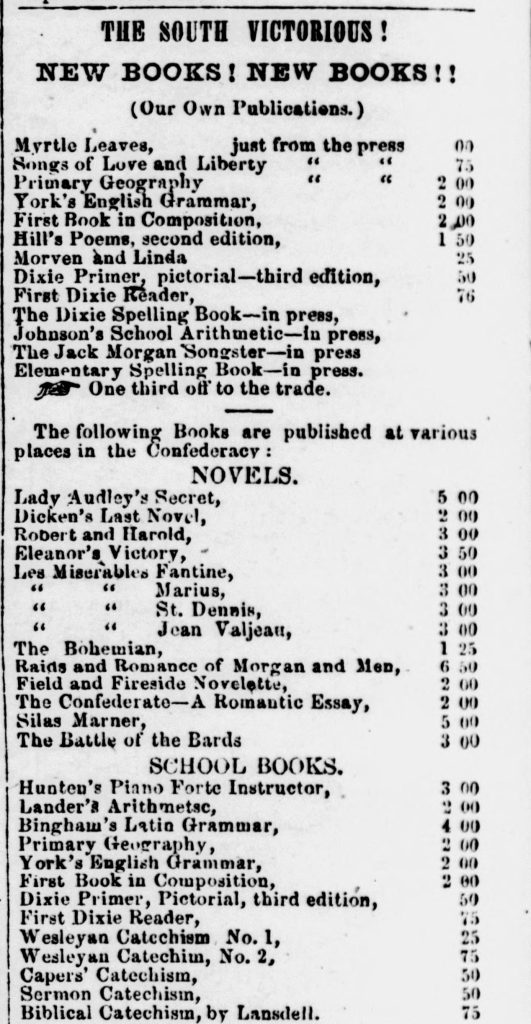

Schools in rebelling states were inundated with pro-Confederate curriculum. Some textbooks focused on Confederate nationalism, while others highlighted Southern institutions. Many were written by Miranda B. Moore, a wartime teacher at Glen Anna Female Seminary in Thomasville, North Carolina.[5]

Moore wrote readers, as well as geography textbooks, instilling Confederate nationalism in students. In her Primary Geography, Moore wrote “In the year 1860 the Abolitionists became strong enough to elect one of their men for President. Abraham Lincoln was a weak man, and the South believed he would allow laws to be made, which would deprive them of their rights. So the Southern states seceded.” While not referencing enslavement’s expansion in that passage directly, the paragraph before it clearly highlighted the issue, with Moore explaining how “the northern people began to preach, to lecture, and to write about the sin of slavery. … And when the territories were settled they were not willing for any of them to become slaveholding. This would soon have made the North much stronger than the South; and many of the men said they would vote for a law to free all the negroes in the country.”[6]

Moore’s geography book described the Confederacy as “a great country! The Yankees thought to starve us out when they sent their ships to guard our seaport towns. But we have learned to make many things; to do without many things; and above all to trust in the smiles of the God of battles.” It also listed Kentucky and Missouri as Confederate states and showed West Virginia still linked to Virginia.[7]

Another geography textbook from 1862 declared, “The most desirable country in North America is the Confederate States. The people are the freest, most enlightened and prosperous in the world;” it also listed Kentucky, Missouri, and the Indian, Arizona, and New Mexico territories as part of the Confederacy, while adding that Maryland “will ally herself with them so soon as free from the shackels [sic] of despotism with which she is now bound.” In keeping with common pro-slavery rhetoric of the time, this System of Modern Geography declared, “Slavery is expressly recognized in the Constitution, as it is in the Word of God, and practiced in all the States, and universally approved of by the people.”[8]

A third Confederate geography textbook omitted Abraham Lincoln in its list of U.S. presidents, while simultaneously including Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware when describing the Confederacy. It also, in hindsight, rather hastily declared that “the Southern States have fought their own way to political independence and the respect and amity of the great nations of the world.”[9]

The appearance of pro-Confederate textbooks and teaching material was not ad-hoc. The Educational Association of the Confederate States of America was formed at a convention in April 1863, adopting a resolution to “publish suitable text books for our schools” while simultaneously calling for educators to “discountenance and disown all persons who, without necessity, resort to reprints of foreign importations.”[10] Professor Edward Boynes of the College of William and Mary, writing a letter supporting the convention, agreed that foreign textbooks, especially from the United States, were packed with “superficial clap-trap, of effect and show.”[11]

The United States, and the loyal states within, also took actions to influence wartime education. Just as within the Confederacy, a primary focus centered around curriculum, with wartime textbooks printed in loyal states hardly mentioning the Civil War at all! The 1862 printing of Johnson’s Family Atlas, the geography textbook approved by the New York City Board of Education, makes no mention of internal conflict, and shows rebellious states as part of the United States.[12] The 1862 printing of First Lessons in Geography did not mention the Civil War at all, instead dividing rebelling states into different regions rather than classifying them together. It did however, mention the state of West Virginia and incorrectly identified Nevada and Colorado as states instead of territories.[13]

The United States also took action to ensure loyalty of its educators, largely via compelling teachers to take oaths of allegiance. Confederate locales under occupation by United States forces often implemented oath requirements or other restrictions. In immigrant-packed New Orleans, Col. Henry C. Deming, acting mayor appointed by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, issued requirements that all New Orleans teachers “must be citizens of the United States.”[14] Military Governor Andrew Johnson directed in occupied Nashville that “all teachers must take the oath of allegiance or resign their position.”[15] In 1864, it was reported that teachers in the areas occupied by United States forces near Nachez, Mississippi, have all “taken the oath.”[16]

Border states required similar oaths. In Baltimore, an oath was required by all public educators, and “all who failed or refused to subscribe” would “vacate their positions.”[17] In Louisville, the school superintendent required an oath of allegiance for all teachers, issued personally by the mayor.[18] Efforts to remove the requirement of such oaths were defeated in the Kentucky Legislature in 1863.[19] As the war ended, Missouri Governor Thomas Fletcher required “teachers to take an oath of loyalty” enforceable by “the entire military strength of the state.”[20] Even far off California required loyalty oaths from educators.[21]

Both sides took steps to regulate education during the Civil War, with loyal states working to guarantee loyal sentiments while rebellious states instilled Confederate nationalism into their youth. The weaponization of Civil War education systems showcases how the conflict impacted society contemporaneously, as well as how the U.S. education system has often become a political weapon throughout U.S. history.

Endnotes:

[1] “Conscription and Exemption,” Southern Confederacy, Atlanta, GA, September 24, 1862.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Exempts in North Carolina,” Semi-Weekly Standard, Raleigh, North Carolina, November 20, 1863.

[4] “Wanted, A Teacher,” Daily Telegraph, Macon, GA, January 1, 1864.

[5] Samuel A’Court Ashe, History of North Carolina, (Raliegh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1925), Vol. 2, 1192.

[6] M.B. Moore, Primary Geography Reader (Raleigh, NC: Branson & Farrier, 1864), Second Edition, 13.

[7] Ibid, 9, 14, 26-28.

[8] John H. Rice, A System of Modern Geography (Atlanta: Franklin Printing House, 1862), 15, 20-21.

[9] K.J. Stewart, A Geography for Beginners (Richmond, VA: J.W. Randolph, 1864), 42-43, 200.

[10] “Teachers Convention,” Enquirer, Yorkville, SC, May 6, 1863.

[11] Edward S. Joynes, Education After the War: A Letter Addressed to a Member of the Southern Education Convention (Richmond, VA: MacFarlane & Ferguson, 1863), 12.

[12] J.H. Colton and A.J. Johnson, Johnson’s New Illustrated Family Atlas (New York: Johnson and Ward, 1862), 40-47; Documents of the Board of Education of the City of New-York, for the Year Ending December 31, 1861 (New York: C.S. Westcott & Co., 1862), 144.

[13] James Monteith, First Lessons in Geography on the Plan of Object Teaching (New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1862), 31.

[14] “Manual of the Bureau of Education,” The Daily Delta, New Orleans, LA, December 4, 1862.

[15] “Accounts from Nashville,” Walton’s Daily Journal, Montpelier, VT, May 8, 1862.

[16] “From the Trans-Mississippi Department,” The Daily Conservative, Raleigh, NC, April 29, 1864.

[17] “Public School Teachers and the Oath,” The Sun, Baltimore, MD, August 28, 1862.

[18] “The Teachers’ Oath,” Daily Journal, Louisville, KY, August 29, 1862.

[19] “From Frankfort,” Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, February 2, 1863.

[20] “Governor Fletcher, of Missouri,” Mirror, Olathe, KS, September 21, 1865.

[21] Maurice H. Newmark and Marco R. Newmark, eds. Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853-1913 (New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1916), 308.

Excellent overview of the opposing views found in the North and South schoolbooks during the war. I was especially surprised at M. Moore’s geography book which depicted Lincoln as a “weak man”.which suggested that radial members of the Republican Party were the real instigators trampling on Southern rights, not Lincoln himself. I think today the Confederate view of many is much the opposite, wherein current southern thought suggests Lincoln was more of an abolitionist, tyrant and clever politician who manipulated Congress and military leaders resulting in downfall of the Confederacy. Once again, “Who was the real Lincoln?”, is still subject to much debate after 160 or so years.

You have not justified use of the horrendous, heavy handed and totally inappropriate term “weaponization.”

One would call this propaganda at best.

You have not told us how many of these books were published, how many were actually used, how many students were involved and provided absolutely no data to substantiate the impact of this material in the classroom and most of all the long term influence and impact on the children.

And as a side comment refer to politicalization of the US public

school system is propaganda itself without substantiating facts and data.

To understand and correctly employ the term weaponization of a school system one must study the German school system from 1933-1945. Weaponization is a legitimate term for: removal of all Jewish teachers, removal of all Jewish students, introduction of bankrupt and unsubstantiated pseudoscience as doctrine to justify discrimination, ostracism and disposal of whole peoples. And the teaching of corrupted biology and genetics to support the false concept of a master race.

And the post educational data is available to confirm the insidious impact of real weaponization of an education system, millions of innocent people murdered by the children educated under a real, weaponized education system.

You must provide much more research and data to even come close to the term weaponization of a school system.

You have only described a pitiful effort to influence a people whose politicians and economic system thrust into war.

Confederate Conscription and the Struggle for Southern Soldiers, by John M. Sacher from LSU Press contains some good anecdotes on what people thought of teachers avoiding conscription and how some soldiers sought out teaching jobs to avoid conscription. If I remember correctly, one soldier wrote his wife multiple times about her getting him a teaching job in his home area of north Louisiana.

Thanks Neil, another great article.

Unfortunately, sore loser Confederates continued this anti-historical trend in public education well into the 20th century with the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) taking the lead. To ensure that history books got the “facts” right, in 1919 the UDC authored and United Confederate Veterans (UCV) published a 32-page pamphlet called A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges, and Libraries. The purpose of the pamphlet was “to inaugurate a movement to disseminate the truths of Confederate history.”

It directed school boards to reject books which did not conform to any one of ten criteria. For example, there is the standard holy scripture of the Lost Cause: The war was not caused by slavery; slavery was really a benevolent institution; the Constitution was a severable compact between sovereign states, and neither perpetual nor national, blah, blah. Some of the other rejection criteria were downright weird. For example, the Federal gov’t was responsible for “the horrors of Andersonville;” and, the South earnestly desired peace and “made every effort to obtain it.” The UDC’s little book even had a solution for volumes already in public libraries. They were to be given the truth test as well. Those that didn’t pass were to have their title pages boldly marked — “Unjust to the South.”

To the modern historian, these criteria sound ridiculous. In 1919, however, these organizations had outsize political power and considerable cultural influence. Thus, by the mid to late 20th century, Lost Cause orthodoxy was in text books throughout the country. Much of the narrative remains in vogue today as we see continued veneration of Confederate luminaries and heraldry and spirited discussion over school names, standards of learning, and textbooks. So, while the muscular UDC and UCV of the last century are long gone, the Lost Cause has had remarkable staying power as evidenced by the overheated discussions we have on ECW.

Here’s the reference and the link for the pamphlet. It is a remarkable and well-written work of “scholarship” as the author, the “illustrious Southern Historian, Miss Mildred Rutherford,” harvested, out of context of course, just the right quote to support her case — some of slickest propaganda I’ve read.

Rutherford, Mildred Lewis. A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges and Libraries. (Athens Georgia: United Confederate Veterans) 1919. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/measuringrodtote00ruth

Thanks Neil, another interesting article.

Unfortunately, unreconstructed Confederates continued this anti-historical trend in public education well into the 20th century with the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) taking the lead. To ensure that history books got the “facts” right, in 1919 the UDC authored and the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) published a 32-page pamphlet called A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges, and Libraries. The pamphlet’s stated purpose was “to inaugurate a movement to disseminate the truths of Confederate history.”

It directed school boards to reject books which did not conform to ten specific criteria. For example, there’s the standard holy scripture of the Lost Cause: the war was not caused by slavery; slavery was really a benevolent institution; the Constitution was a severable compact between sovereign states, blah, blah.

The UDC also included a recommendation for volumes already in libraries — they were also subject to the southern truth test. For those books not passing muster, southern librarians were requested to boldly mark their title pages with the statement “Unjust to the South.” Finally, the UDC promised a forthcoming list of books, both condemned and commended, for use by educators and librarians.

To the modern historian, this UDC pamphlet and the idea of “southern truths” sounds ridiculous. In 1919, however, these organizations had outsize political clout and considerable cultural influence. Thus, by the mid to late 20th century the Lost Cause narrative was in text books throughout the country. Much of this narrative remains in vogue today as we see continued veneration of Confederate luminaries and heraldry and contentious discussions over school names, standards of learning, and textbooks. Closer to home, we all see these overheated discussions frequently right here on ECW. So, while the muscular UDC/UCV organizations of the 19th and 20th centuries are long gone, the Lost Cause has had remarkable staying power.

PS – Here’s the reference and the link for the pamphlet. It is a remarkable piece of “scholarship” as the author has harvested, out of context of course, just the right quote or unverifiable fact to support her case. It’s the slickest piece of propaganda I’ve ever read.

Rutherford, Mildred Lewis. A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges and Libraries. (Athens Georgia: United Confederate Veterans) 1919. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/measuringrodtote00ruth

I find it a little ironical to complain about books which “showed West Virginia still linked to Virginia” while at the same time showing a photograph of Bethany College, West Virginia, as “Antebellum imagine [sic] of students from Bethany College, Virginia”, which is a type of historical “deadnaming”. I find that this practice is usually confined to West Virginia and not, say, Maine, which had been part of Massachusetts. Its prestate notables and places are not usually denoted as “Massachusetts”.