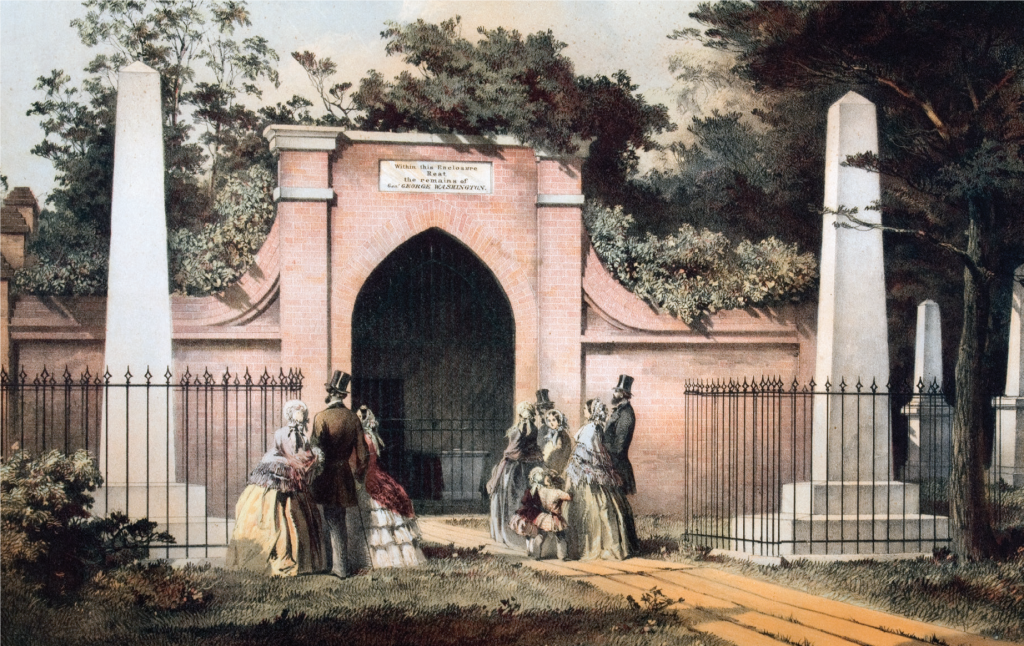

A Confederate Buried at Mount Vernon?

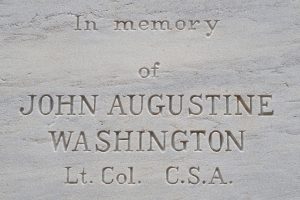

Visitors to George Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon might be surprised to see that the “Father of the Nation” shares his final resting place with a memorial commemorating a Confederate soldier. Lieutenant Colonel John Augustine Washington III, the general’s great grandnephew, lies adjacent to George Washington’s remains in the Mount Vernon family plot. Or at least, that’s how it appears. A small obelisk bears the following inscription:

In memory of

John Augustine Washington III

Lt. Col. C.S.A.

1820-1861

And his wife

Eleanor Love Sheldon

1824-1860

Last Private Owners of

Mount Vernon

Buried at

Charles Town, West Virginia

So why was Washington buried 57 miles away from Mount Vernon, despite being the last member of the Washington family to own the estate? And why does a monument appear to mark his grave in the Washington family tomb? These questions point to Washington’s premature death at the outset of the Civil War.

John Augustine Washington III was born in 1821 on his father’s Blakely plantation in Jefferson County, Virginia (now West Virginia). Washington held strong familial connections to America’s founding, with ties to the Revolution on both his mother’s and father’s sides. However, all pale in comparison to his lineage as the great grandnephew of the nation’s first president. In 1829, Washington’s father inherited Mount Vernon. When his father died of heart disease three years later, ownership of the ancestral Washington estate passed to his mother.

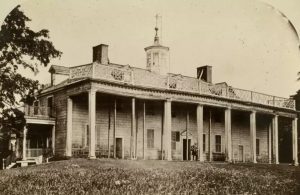

As an adolescent, Washington spent a great deal of time away from home to receive an education. Despite his desire to lead an aristocratic life, his mother encouraged him to attend the University of Virginia, where he graduated in 1840. When he returned home to Mount Vernon, Washington proposed to manage daily operation of the estate in return for an annual stipend of $500 and ownership of 22 slaves. His mother agreed, and Washington assumed leadership of what would one day be his plantation. However, the young man quickly became disillusioned with the property, for he had not only inherited George Washington’s mansion, but also the president’s legacy. Tourists flocked to the house and grounds by the thousands. Washington struggled to share Mount Vernon with visitors while also keeping it as his private residence. Not to mention, the mansion had fallen into disrepair, and its land (which provided a large source of the estate’s revenue) had been carved up by the president’s many descendants.[1]

Washington’s mother died in 1855, and Mount Vernon officially passed to him. For years, Washington rebuked offers from land speculators to purchase the property. And after his mother’s death, he redoubled his efforts to maintain the home. However, the young man struggled to balance his resolve to provide for his growing family as well as meet the demanding needs of preserving the mansion. He continued to reject offers to buy the property until he spoke with an unlikely visitor: Ann Pamela Cunningham. Cunningham had recently traveled up the Potomac River and noticed the dilapidated state of Mount Vernon. Then and there, she decided to launch a crusade to preserve it. A few months later, Cunningham offered to purchase the mansion and 202 acres of land and restore it, and Washington heartily accepted. (Cunningham’s ownership of Mount Vernon and her subsequent founding of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association is considered the beginning of the historic preservation movement in America.)[2]

Free from the financial burden of Mount Vernon (and $200,000 richer), Washington moved his family to another estate in Fauquier County, Virginia called Waveland. There, he and his family prepared to settle down. Their tranquility was short lived, though. His wife Nelly died from childbirth in 1860, leaving Washington a widower with seven children between the ages of one and 16. However, this did not dissuade him from volunteering in the Confederate army the following year. He departed Waveland on April 30, 1861, just 17 days after Federal troops abandoned Fort Sumter. On May 13, the Provisional Army of Virginia appointed him to the staff of General Robert E. Lee, commanding Confederate forces in western Virginia. Washington was commissioned a lieutenant colonel and served alongside Lt. Walter H. Taylor as one of Lee’s aide-de-camps.[3]

Many throughout the South viewed Washington’s appointment in the Confederate army as an omen for success in their “second war of independence.” The Richmond Dispatch praised Washington for defending the “liberty secured to the whole country by [. . .] his distinguished relative.” While Confederate newspapers heralded Washington as a hero, Northern newspapers condemned him as a traitor. Rumors swirled about that Col. Washington had stolen the body of his great granduncle and smuggled it to the Confederacy. “If it be true the American people will not be apt to rest long until summary vengeance having been visited upon his dastardly carcass,” trumpeted The Morning Democrat in Davenport, Iowa.[4] Nevertheless, Washington felt called to serve the Confederacy. Perhaps the revolutionary spirit of his forebearer inspired him to aid the fledgling rebellion—a decision for which he paid a high price.

On September 12, 1861, Union forces in western Virginia engaged and defeated Lee’s men at the battle of Cheat Mountain. The following day, Lee ordered his son, Capt. William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee, and two cavalrymen to conduct a reconnaissance on the Union right flank. Hearing of the party’s need for another man, Col. Washington volunteered to accompany the mission. As the four riders rounded a hairpin turn on a mountain road, three Union pickets from the 17th Indiana Infantry Regiment ambushed them. The soldiers stood from their concealed position and fired a volley into the horsemen. Three bullets struck Washington in the chest. As the colonel fell from his horse, Rooney Lee and the two troopers galloped off to safety, leaving Washington mortally wounded in the road. The Union pickets quickly captured him and called for a stretcher to transport him back to their camp at Elkwater. Washington allegedly asked for a drink of water, but he died before a Union soldier could fetch his canteen.[5]

When Rooney Lee returned to headquarters, he recounted the mission to his father. General Lee sent a messenger under a flag of truce to the Union commander, Brig. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds, to inquire about Washington’s condition. If he had died, Lee requested that Reynolds return the body to the Confederates. Reynolds abided and ordered that Washington’s body be transported back to Rebel lines. A small Confederate force, commanded by Lt. Col. William Edwin Starke, received the ambulance containing the corpse. “Col. Washington’s temerity killed him,” Starke remarked coldly when he saw the body. “He was advised not to go where he did, but was on his first expedition and extremely anxious to distinguish himself.”[6]

Much like his decision to join the Confederate army, Washington’s death inspired a hailstorm of praise and criticism. Richmond newspapers mourned him as one of the first martyrs in their war for independence. Lieutenant Walter Taylor remembered that the death of his friend and comrade served as a reckoning of sorts. “As I looked upon his inanimate form as it lay there on the side of Valley Mountain, I thought of that other valley, of the shadow of death, through which he had just passed, never to return; I thought of those dear little girls of his and of the utter desolation that had so suddenly come to their happy home; and I began to realize something of the horrors of war,” the young officer wrote.[7]

While Southerners grieved for Washington, Northerners maligned him as a traitor who received a just retribution for his crimes. “Thus has gone the name of Washington; the last inheritor, a traitor to the Government, the great ‘Father of his Country’ labored to construct; in open rebellion against it; dodging the valiant men who are endeavoring to perpetuate it,” recalled the Union quartermaster who oversaw transportation of Washington’s body. One Northern correspondent wrote to his readers, “I have the pleasure, and it is indeed a pleasure, to send you the news of the death of John A. Washington,” and continued his scathing assessment of the colonel’s character by stating “very few tears will be shed at [his] death.”[8] A Wisconsin reporter felt similarly. “My wish is that the memory of the great immortal Washington will not be insulted by laying the bones of the wretched namesake upon any portion of Mt. Vernon,” he argued. “The distance between the burial places should be continents.”[9] Though Washington’s grave does not lie “continents” away from his ancestor, he was not buried at Mount Vernon. Instead, he and his wife were laid to rest in the Zion Episcopal Churchyard in Charles Town, West Virginia—not far from his birthplace at Blakely plantation.

But as Northerners and Southerners claimed Washington as a traitor and martyr, a touching story emerged from such vitriolic rhetoric. On September 14, 1861, Gen. Lee wrote to Washington’s 17-year-old daughter, Louisa, to inform her of her father’s death. “With a heart filled with grief, I have to communicate the saddest feeling you have ever heard,” he began. “May our Father who is in Heaven enable you to bear it, for in his inscrutable Providence, abounding in mercy, & omnipotent in power, He has made you fatherless on earth.” The general’s letter reveals his great respect for Washington, who Lee believed had fallen “in the cause [to] which he had devoted all his energies, and in which his noble heart was earnestly enlisted.” Lee continued: “We have shared the same tent, and morning and evening has his earnest devotion to Almighty God elicited my grateful admiration. He is now safely in Heaven, I trust, with her he loved on earth. We ought not to wish him back. May God in his mercy, my dear child, sustain you.” [10]

Lee maintained a frequent correspondence with Louisa both during and after the Civil War. In August 1865, he gifted her Washington’s final dispatch, written just moments before he died. “You know how I have sorrowed at his loss,” Lee professed, “but you cannot know what great love I feel towards you, your sisters, and brothers.”[11] And three years later, the general advised Louisa on an appropriate inscription for her father’s cenotaph at Mount Vernon. “It might not be out of place to add to the inscription on the face, ‘the last proprietor of Mount Vernon of the family of Washington,'” he suggested, adding that “in the present state of affairs, it would not be wise, I think, to state more particularly his devotion and sacrifice to his state.”[12] It seems Louisa generally heeded Lee’s advice, for the only mention of Washington’s service in the Confederate army on his cenotaph is “Lt. Col. C.S.A.”.

John A. Washington’s lineage and legacy serve as a reminder of the nation’s complicated past. He quickly found himself caught up in a conflict in which both sides claimed his ancestor as a founding figure, while his death and subsequent burial—far from his ancestral home—illustrate the polarizing climate of the American Civil War. Even now, visitors to Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon are subtly reminded of the national divisions of the 1860s by Washington’s cenotaph at the grave of America’s first president, traditionally a symbol of the nation’s unity.

[1] Whitney Martinko, Historic Real Estate: Market Morality and the Politics of Preservation in the Early United States, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 199.

[2] Robert F. Dalzell, Lee Baldwin Dalzell, George Washington’s Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 226-227.

[3] Ronald S. Coddington, “Blessed Martyr, Vile Traitor,” Military Images, vol. 42, no. 1 (Winter 2024), 57-58.

[4] Coddington, “Blessed Martyr, Vile Traitor,” 58.

[5] Walter Herron Taylor, General Lee: His Campaigns in Virginia, 1861-1865, With Personal Reminiscences, (Norfolk, VA: Nusbaum Book and News Company, 1906), 30; “Death of John A. Washington,” The Manitowoc Pilot, October 4, 1861, Newspapers.com, (accessed May 24, 2024).

[6] Coddington, “Blessed Martyr, Vile Traitor,” 61.

[7] Taylor, General Lee, 30.

[8] “Death of John A. Washington,” The Manitowoc Pilot, October 4, 1861, Newspapers.com, (accessed May 24, 2024).

[9] Coddington, “Blessed Martyr, Vile Traitor,” 61.

[10] Robert E. Lee to Louisa Washington Letters, WLU-Coll-0669, Special Collections and Archives, James G. Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University.

[11] Robert E. Lee to Louisa Washington Letters, WLU-Coll-0669, Special Collections and Archives, James G. Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University.

[12] Robert E. Lee to Louisa Washington Letters, WLU-Coll-0669, Special Collections and Archives, James G. Leyburn Library, Washington and Lee University.

Excellent article. Robert Lee was married to George and Martha Washington’s great-granddaughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee.

Thanks! Yes, the Lee-Washington family tree is an interesting one to study.

A very good article, factual and useful in explaining the complexity of the War. Oddly, there’s no Wikipedia entry for JAWIII, but there is a good article on Waveland, and JAWIII’s involvement with it, on historicprincewilliam.org/county-history/structures/waveland-estate.html. He hired a manager, James Thomas Ford, whose son Robert Ford moved West and shot Jesse James. Who knew? JAWIII’s many children were cared for by his brother; the estate eventually passed to Mr. George R. Thompson Jr. who has restored it. For the record, George Washington freed the Washington slaves at Mt. Vernon in his 1799 will; other family members on did not (GW had nine siblings; three full brothers and three half-brothers). The Custis slaves were held in trust for Martha Custis Washington and her heirs; her son died before she did, and her grandson George Washington Parke Custis, who built Arlington, freed them in his 1857 will (his wife, Mary Fitzhugh Custis was an Abolitionist).

Thanks for sharing; I did not know about the Jesse James connection!

Thanks for the article! You had to feel for the young Washington, if you visit the Mansion you can see pictures of the dilapidated condition! He had to be over whelmed. From the front porch he owned the land as far as you could see in every direction! GW wanted it that way and road his horse around managing his vast estate! Today all you see are lines of tour buses! One interesting thing that happened during the Civil War was both sides treated the estate with reverence and didn’t disturb the estate because of the relationship to GW! Unlike Lee’s Mansion in Arlington! If you look at your picture showing the tomb, on both side of the doorway are masonry walls that Civil War soldiers etched their names in when they visited the tomb during the war! GW freed his personal slave (he’s buried on the estate) and freed the rest in his will to be released after Martha died so she could run the estate! Just like he was supposed to be buried under the rotunda in the Capitol, he didn’t want to be buried there and Martha complied with that too! We can never thank The Mount Vernon Women Association enough for saving this national treasure! There’s nothing like the view and historical moment sitting in the high back rocking chairs on the rear veranda overlooking the Potomac River!