Guardians of the Nation’s Glory: The Civil War Memorials of Northwest Washington, D.C., part II

ECW welcomes back guest author Kyle R. Hallowell

Introduction

This post continues my previous one, discussing Civil War memorials’ construction, funding, and dedication in northwest Washington, D.C. Below is a list of memorials I recommend visiting and some interesting facts about them. This list is in no way exhaustive and only highlights a few of the more noteworthy statues in Washington. I have intentionally omitted the Nuns of the Battlefield Memorial, which is featured in another post, and the Winfield Scott Hancock Memorial, the construction of which is straightforward and less colorful than the ones listed below.

Memorials

Major General George Gordon Meade Memorial

Like the man himself, the memorial to George Meade was overlooked and subordinated to the memorials of other more noteworthy and popular Union generals. Meade was the last senior Union officer to be memorialized in the capitol, with the dedication occurring on October 19, 1927.[1] Meade’s memorial was a gift from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and was initially erected in front and to the north of the Ulysses S. Grant memorial in front of the Capitol.

Because six decades had passed between the end of the war and the dedication, the ceremony drew a small crowd, and the ceremony’s featured speaker, President Calvin Coolidge, was born the same year that Meade died. Why did it take so long for Meade, the victor of Gettysburg, to be memorialized in the nation’s capital? The primary reason is the bitter infighting between the Commission of Fine Arts and the Meade Memorial Commission.

On June 14, 1911, the Pennsylvania State Legislature provided for the establishment of a Meade Memorial Commission. Four years later, Congress did the same, with the stipulation that the Meade Memorial meet the approval of the Commission of Fine Arts.[2] The chairman of the Meade Memorial Commission, John W. Frazier, was a former subordinate of Meade’s who had a self-professed disdain for “culture.”[3] Frazier was a rude, stubborn, politically well-connected curmudgeon who refused to compromise with the Commission of Fine Arts. His obstinance resulted in twelve years of gridlock, which only broke with his death in 1918. That same year, a Philadelphia-based sculptor named Charles Grafly was given the commission to create the Meade memorial. Grafly produced a monument that art critics hailed as a triumph.[4] In 1969, Meade’s statue was dismantled and moved to permit highway construction under the National Mall. Meade’s memorial then spent fourteen years in storage and was subsequently re-erected in 1983, where it currently overlooks the spot where Meade rode at the head of his victorious Army during the Grand Review in May 1865.

Major General John A. Rawlins

John Rawlins was nine years Ulysses Grant’s junior. Yet, these two men became incredibly close friends during the war, with Rawlins serving as Grant’s aide-de-camp, staff officer, secretary of war, and moral conscience. Rawlins, whose own father was an alcoholic, ensured that Grant remained sober during the war. In 1864, Rawlins contracted tuberculosis, from which he died on September 6, 1869. Grant could not see his friend and confidant before his passing and subsequently sought to memorialize him with a statue in the capitol.

That same year, Congress authorized bronze cannons to be melted down for the statue. After that, little happened until Grant personally wrote to Secretary of War William Belknap, calling attention to the matter. Soon after, Illinois Senator and Union veteran John A. Logan introduced a bill appropriating $10,000 for a Rawlins memorial.[5] The bill passed and was signed into law by Grant.

A call for model submissions was put out in 1872, and the commission responsible for selecting a sculptor chose Joseph Bailly, who had previously sculpted models of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia. The statue of Rawlins was placed in Rawlins Park in 1874, which was unkempt and remote. After complaints were received about the statue’s surroundings, Rawlins’ statue was moved to a new location and then subsequently moved to another location to make way for a newspaper factory. In 1931, the construction of the National Archives building forced the Rawlins’ statue to be moved again, this time back to its original location where it stands today. In 1963, a Wyoming congressman unsuccessfully tried to have the statue moved to Rawlins, Wyoming.[6]

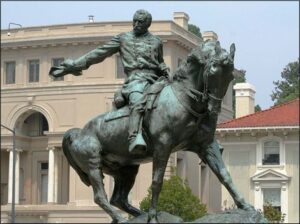

Major General George B. McClellan

Creating a memorial for Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan involved all the drama, ego, and political conflict that one should expect from anything involving “The Young Napoleon.” McClellan’s statue was the first erected in the capitol by the Society of the Army of the Potomac and had to overcome multiple delays and indecision imposed by the society and McClellan’s widow, Ellen Marcy McClellan.

Shortly after he died in 1885, the society received a $50,000 appropriation from Congress to create a McClellan memorial. Sixteen years later, the McClellan Statue Commission, composed of well-known sculptors and advised by Mrs. McClellan, requested that artists submit models for consideration. They received thirty models and then narrowed their selection down to four. These four were exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in the spring of 1903, but all four received severe criticism, causing the commission to deem all four models unsatisfactory.

One month later, the commission invited other sculptors to submit a model for the McClellan equestrian statue. One of the commissioners, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, wanted his pupil, Frederick MacMonnies, who previously gained notoriety for designing the central fountain at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, to be awarded the commission and took steps to ensure he received it. In February 1905, MacMonnies was awarded the commission and soon after sent photographs of his sculpture to Mrs. McClellan and her son, George, who was then serving as the mayor of New York City. [7] Both were critical of the sculpture and said that the horse’s body was too long, his tail too “lively,” and that McClellan’s sword was improperly hitched.[8] Despite these criticisms, MacMonnies changed little in his model.

The selection of the memorial’s location proceeded similarly. Because the society, perhaps embodying the deliberate manner of their former chieftain, took so long to fundraise and award a commission, all of the prime locations for statues in D.C. were occupied. The society finally found an unoccupied lot in Kalorama Heights that had previously been a Union army camp in 1861.[9] With a site selected and the sculpture decided upon, the society, in close consultation with Mrs. McClellan, began planning the dedication ceremony, which was initially scheduled for May 15, 1907. After the invitations had been sent, Mrs. McClellan suddenly “changed her base” by leaving for Europe and wrote to the society president, Horatio King, requesting that the ceremony be rescheduled for November.[10] Mrs. McClellan also wrote to then Secretary of War William Howard Taft with her request, which Taft rebuffed, citing concerns for the veterans’ health in the November weather. King and Taft drew the ire of the old widow. They commiserated with each other in a private letter written by Taft to King, “By the way, I am in disgrace for not too consenting to murder the old Vets by having open air exercises in November.” [11] The dedication ceremony occurred on May 2, 1907. Major generals Oliver O. Howard and Grenville Dodge spoke, and President Theodore Roosevelt accepted the statue on behalf of the American people.

General Phillip H. Sheridan, Sheridan Circle

According to legend, shortly before his death, Philip Sheridan walked past the Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott Memorial a few blocks from his home. He remarked to his wife, “Whatever you do after I am gone, don’t put me on a horse like that.” 12 Sheridan emerged from the war as the Union’s preeminent cavalry hero. He and his mount, Rienzi, gained lasting fame for their heroic actions at the battle of Cedar Creek. Sheridan arrived on the field after the battle had already begun and found his troops being routed. He rode amongst them, swinging his hat and shouting, “Turn back, men! Turn back! Face the other way!”[12]

This was the scene that Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor of Mount Rushmore and, ironically, the Confederate memorial at Stone Mountain, would try to capture in his memorial of Sheridan. The commission for the monument was initially awarded to John Quincy Adams Ward, but after six years, he produced nothing but a life-size study of Sheridan’s head. Ward was fired in 1905, and Borglum used his charm and knowledge of Sheridan to influence Mrs. Sheridan’s decision to award him the commission. Sheridan’s son, Phillip Sheridan Jr., then an Army lieutenant who greatly resembled his father, was given leave to pose for Borglum. Borglum’s sculpture tremendously pleased the Sheridan family, and the dedication ceremony on November 25, 1908, drew a bigger crowd than the dedication of the George McClellan statue. President Theodore Roosevelt, a cavalryman himself, spoke highly of Sheridan at the ceremony, lauding him as “brilliant” and “original” and praising his service on the Western plains after the war.[13]

General William Tecumseh Sherman Monument

Next to the Ulysses Grant Memorial, the Sherman Monument is the largest and most complex of the capitol’s Civil War memorials. Dedicated on October 15, 1903, the Sherman Monument consists of an equestrian statue adorned with bas-relief panels, portrait medallions, sculpture groups, life-size soldiers, and lengthy inscriptions. Sherman’s Civil War service made him a household name, and his postbellum service as commanding general of the United States Army cemented his place in history as one of America’s great heroes.

After he died in 1891, the Society of the Army of the Tennessee undertook an effort to memorialize Sherman by lobbying Congress for $50,000 and establishing the Sherman Monument Commission, both of which were done. The society then began fundraising by sending nationwide mailers, but they only received $14,469.91 in contributions, requiring Congress to double its appropriation.[14] In April 1896, the commission received models from twenty-three sculptors and narrowed that down to four finalists. Of the four, Danish-born Carl Rohl-Smith was chosen despite his sculpture receiving harsh criticism from other prominent sculptors. In 1897, Rohl-Smith began his work and had completed most of the sculpture when he died unexpectedly during a visit to Denmark in 1900.

Rohl-Smith’s wife received permission to have other artists continue her late husband’s work, and they subsequently had cast sections of the 14-foot-tall statue ready for assembly by August 1903. During the time that Rohl-Smith was sculpting, the society was determining an appropriate location for the memorial. They found an ideal location for the monument where Sherman watched his troops parade during the Grand Review of the Union army. With the monument assembled and the location finalized, the society proceeded with the dedication ceremony, which President Roosevelt attended. One of Sherman’s former subordinates, Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge, presided over the ceremony. President Roosevelt exhibited his characteristic vigor during the ceremony and used his dedication speech as a “bully pulpit” to encourage the American people to emulate the example Sherman and his fellow veterans set. Roosevelt’s words still resonate today: “Their blood and their toil, their endurance and patriotism, have made us and all who come after us forever their debtors.”[15]

Memorial Locations

Major General George Gordon Meade Memorial

Major General George B. McClellan

General William Tecumseh Sherman Monument

Kyle R. Hallowell is an active-duty U.S. Army Strategist currently studying International Policy at Texas A&M University. He has a BA in History from Norwich University and has been passionate about the Civil War since childhood. He lives in Northern Virginia with his wife and son.

Bibliography

“Honor the Memory of Phil Sheridan.” The Evening Star (Washington D.C.), November 25, 1908, 1,12. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83045462/1908-11-25/ed-1/?sp=1&r=-0.085,-0.001,1.151,0.501,0.

Jacob, Kathryn Allamong. Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Keim, D.B.R., A.P.C. Griffin, and Society of the Army of the Tennessee. … Sherman: A Memorial in Art, Oratory, and Literature by the Society of the Army of the Tennessee with the Aid of the Congress of the United States of America. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904. https://books.google.com/books?id=iBQ9AQAAIAAJ.

“President Accepts Meade Memorial as Gift to Nation.” The Evening Star (Washington D.C. ), October 19, 1927 1927, 42. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1927-10-19/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Sheridan Arrives.” A Victory Turned from Disaster, U.S. National Park Service, Cedar Creek & Belle Grove National Historical Park, Updated December 20, 2021, accessed May 30, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/sheridan-arrives.htm.

[1] Kathryn Allamong Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C. (Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 54, 183.

[2] “President Accepts Meade Memorial as Gift to Nation,” The Evening Star (Washington D.C. ), October 19, 1927 1927, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1927-10-19/ed-1/seq-1/.

[3] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 55.

[4] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 58.

[5] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 112.

[6] Ibid, 113.

[7] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 132.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 132.

[10] Ibid, 133.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Sheridan Arrives,” A Victory Turned from Disaster, U.S. National Park Service, Cedar Creek & Belle Grove National Historical Park, updated December 20, 2021, accessed May 30, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/sheridan-arrives.htm.

[13] “Honor the Memory of Phil Sheridan,” The Evening Star (Washington D.C.), November 25, 1908, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83045462/1908-11-25/ed-1/?sp=1&r=-0.085,-0.001,1.151,0.501,0.

[14] Jacob, Testament to Union: Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., 92.

[15] D.B.R. Keim, A.P.C. Griffin, and Society of the Army of the Tennessee, … Sherman: A Memorial in Art, Oratory, and Literature by the Society of the Army of the Tennessee with the Aid of the Congress of the United States of America (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904), 64. https://books.google.com/books?id=iBQ9AQAAIAAJ.

[16] Keim, Griffin, and Tennessee, … Sherman: A Memorial in Art, Oratory, and Literature by the Society of the Army of the Tennessee with the Aid of the Congress of the United States of America, 54.

Outstanding and needed reminder to all. Each of these officers paid a high, personal price for the battle years and stress of command during which The Guardians of the Nation’s Glory were indeed the Instruments of the Nation’s Survival.

Each of them brought unique skills and personalities to the greatest crisis the Nation has ever endured and whether loved or tolerated by Lincoln, contemporaries, or historians they all played a major role on the Civil War stage.

The only special bravery and courage I would note is for General Hancock. While working in DC I toasted his courage with Champagne at the foot of his statue each July 1 at 4pm as he was indeed the “Finest officer in the Union Army in the immediate presence of the enemy.” And proved this again and again until his Gettysburg wound made field duty too difficult.

He returned to duty in May of 1864 fighting, riding, and leading a Corps with a

19th century catheter, necessary because of internal urinary damage from the Gettysburg wound. His combat record is more remarkable in the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, the Overland Campaign and on into Petersburg with the pain and inconvenience of a catheter.

Each of these officers should hold a place of honor not just among those who study them, but in the hearts and minds of every American who owes the survival of the Nation to them and the men they commanded and fought with.

Thanks for your comment, Charles! Hancock was indeed a “superb” and superlative soldier. It was a tough decision to omit him from the post, but the story of the creation, funding, and erection is less colorful than the ones listed above. After Hancock died, Congress promptly decided to commemorate him with a monument, which they quickly funded. An artist was found, and he produced a suitable sculpt, subsequently cast and erected.

Fun Note: In the film Shawshank Redemption, Andy Dufresne crosses into Mexico at Fort Hancock, Texas, named for Winfield S. Hancock. When I was stationed in El Paso, I made time to visit the town. Sadly, little of the Fort remains.

thanks Kyle, another great installment on your DC monument series … Sheridian is my favorite for the reason you state — the viewer is much closer and the sculpture — horse and rider –convey a real sense of action … your piece also conveys the politics, processes and personalities involved in public history.

I am glad that you enjoyed reading it Sir! You are spot on about the political element of the statues. Statues have always been mildly controversial and highly politicized because of their power to influence and shape public historical memory.

Forgot to mention two very good books on public history — Monument Wars by Kirk Savage … the author’s politics get a little tiresome, but the scholarship is great ,,, the other is History Wars: The Enola Gay and Other Battles for the American Past, edited by Tom Engelhardt … read both in a War & Society seminar while a grad student

So McClellan’s horse has one hoof off the ground… wounded during service?

Wish the Hancock statue was a little closer to the ground, too.

Really well written. Thanks