Fourteen Union Heroes from a Forgotten Battle

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Nigel Lambert

Established on July 12, 1862 (i.e., during the Civil War), the Medal of Honor is awarded in the name of Congress to a person who, while a member of the U.S. Armed Services, distinguishes themselves conspicuously by gallantry above and beyond the call of duty. The brave deed must have involved self-sacrifice and risk of life. While the Medal of Honor is now the highest military decoration attainable by a U.S. armed forces member, it was the only one during the Civil War. Thus, it was often awarded for reasons that would not now satisfy the stringent modern criteria. A large percentage of Civil War Medals of Honor were associated with actions involving flags.

Of the 1,523 Medals of Honor awarded to Civil War soldiers, 14 were for actions during the battle of Hatcher’s Run in the Petersburg Campaign [1]. For a largely forgotten battle that represents a sizable number [2]. The recipients are listed below:

Buckingham, David E., 4th Delaware. Sagelhurst, John C., 1st New Jersey Cavalry.

Cadwalladar, Abel G., 1st Maryland. Sands, William, 88th Pennsylvania.

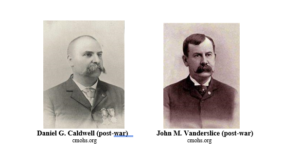

Caldwell, Daniel G., 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Smith, Francis M., 1st Maryland.

Coey, James, 147th New York. Smith, S. Rodmond, 4th Delaware.

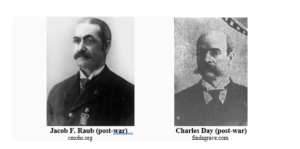

Day, Charles, 210th Pennsylvania. Spillane, Timothy, 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Delaney, John C., 107th Pennsylvania. Thompson, John J., 1st Maryland.

Raub, Jacob F., 210th Pennsylvania. Vanderslice, John M., 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

The stories behind these brave acts highlight many of the battle’s notable actions.

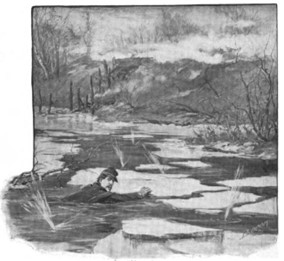

Early on February 5, 1865, the Union 5th Corps had to cross the partially frozen Rowanty Creek at Monk’s Neck Bridge. However, Confederates destroyed the bridge and occupied rifle pits on the opposite bank. Brigadier General James Gwyn’s brigade was tasked with taking the crossing at all costs. During the engagement, Lt. David Buckingham and Capt. Rodmond Smith, both with the 4th Delaware, swam across the icy creek amid enemy fire to help secure the crossing [3].

On the following day, around 1:30 p.m., Maj. Gen. David McM. Gregg’s cavalry received orders to push back a Confederate force along Vaughan Road. Although the Confederate position proved too strong and the Yankee cavalrymen were repelled, four soldiers received medals from the engagement. During the initial charge, Pvt. John Vanderslice was the first man to reach the Rebel rifle pits, which were temporarily captured. Sgt. John Sagelhurst led a charge on the enemy’s rifle pits. He carried a severely wounded commissioned officer off the field while under heavy Confederate fire [4]. During one charge, Pvt. Timothy Spillane displayed gallantry and good conduct in action and, despite suffering two wounds, showed a reluctance to leave the field.

During a mounted charge, Sgt. Daniel Caldwell dashed into the center of the enemy’s line. He allegedly captured five Confederates and the colors of the 33rd North Carolina Infantry. Caldwell’s award was the only one of the 14 issued during the war. The other Hatcher’s Run Medals of Honor were awarded decades later, mainly in the 1890s.

The Caldwell story is problematic because the 33rd North Carolina was not present at the battle. I described this mystery in a recent article [5]. Remnants of the captured flag reside in the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia. Following research by the museum and independent vexillologists, the flag was “tentatively attributed” to the 23rd North Carolina. Researchers understandably reasoned that a typographical error had occurred in the Official Records. The 23rd belonged to Brig. Gen. Robert Johnston’s brigade. In traditional accounts, Johnston’s troops fought along Vaughan Road on February 6, consistent with the assumption. However, we now know that Johnston wasn’t present at the battle, and on the day his brigade fought solely around Dabney’s Mill against Union infantry. The only North Carolina infantry regiments on Vaughan Road were those in Brig. Gen. William G. Lewis’s Brigade: 6th, 21st, 54th, and 57th. The mystery of which flag cavalryman Caldwell captured remains unresolved.

During the same afternoon, but over a mile further north, fierce fighting occurred around a large sawdust pile at Dabney’s Mill. The site changed hands at least three times. Corporal Abel Cadwalladar and Cpl. John Thompson, both with the 1st Maryland, received medals for gallantly planting the national and state flags on the enemy’s works in advance of their regiment. Amid the fighting, Sgt. William Sands captured a Rebel unit’s colors in the face of a deadly fire and brought them inside the Union lines.

During the same afternoon, but over a mile further north, fierce fighting occurred around a large sawdust pile at Dabney’s Mill. The site changed hands at least three times. Corporal Abel Cadwalladar and Cpl. John Thompson, both with the 1st Maryland, received medals for gallantly planting the national and state flags on the enemy’s works in advance of their regiment. Amid the fighting, Sgt. William Sands captured a Rebel unit’s colors in the face of a deadly fire and brought them inside the Union lines.

During the chaotic engagement that mostly occurred in densely wooded and swampy terrain, one of Gwyn’s regiments fell into disarray, and their color bearer was killed. Fighting in a neighboring regiment, Pvt. Charles Day seized the colors of the troubled unit and bore them throughout the remainder of the engagement. In the same regiment as Day, Assistant Surgeon Jacob Raub also received an award. Initially stationed in a Federal field hospital far from the fighting, Raub learned that his regiment had entered the battle without a surgeon. He obtained permission to advance with them, and while attending to wounded soldiers under fire, he observed enemy movements that threatened the flank. Still under severe fire, he found division commander Maj. Gen. Romeyn Ayres and informed him of what he’d seen. Ayres quickly changed the direction of the nearest Union brigade in time to save his flank.

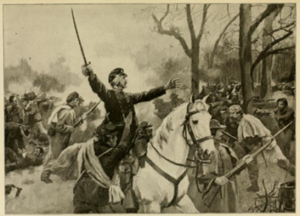

In Brig. Gen. Henry A. Morrow’s brigade, Maj. James Coey had an eventful time around Dabney’s Mill. In the early afternoon, his comrades refused to advance despite the pleas of the brigade commander. Coey seized his regimental colors and marched towards the enemy. His action caused the entire brigade to follow. Later in the fight, as the Rebels aggressively attacked the Federal line, Coey received a bullet below the left eye, the ball coming out behind his right ear. Carried off the field by two comrades, he regained consciousness. After acquiring a horse, Coey returned to the front and attempted to rally his men while his two friends held him in the saddle.

In Brig. Gen. Henry A. Morrow’s brigade, Maj. James Coey had an eventful time around Dabney’s Mill. In the early afternoon, his comrades refused to advance despite the pleas of the brigade commander. Coey seized his regimental colors and marched towards the enemy. His action caused the entire brigade to follow. Later in the fight, as the Rebels aggressively attacked the Federal line, Coey received a bullet below the left eye, the ball coming out behind his right ear. Carried off the field by two comrades, he regained consciousness. After acquiring a horse, Coey returned to the front and attempted to rally his men while his two friends held him in the saddle.

In the late afternoon, the Confederates routed the Federals at Dabney’s Mill. The Yankees fell back in confusion to their breastworks along Hatcher’s Run. The underbrush began to catch fire from sparks produced by the firing. As Sgt. John Delaney (Morrow’s brigade) reached the safety of the Union breastworks; he noticed some wounded men left behind in the now burning “no man’s land.” Delaney called for volunteers to help bring in the wounded. None were forthcoming. He leaped over the Union breastworks alone and ran to the first wounded man, “and lifting him on his back, he started on the return amidst a storm of bullets that nipped his clothing and cut the ground from beneath his feet.”

During the Federal rout, Col. John Wilson, commander of the 1st Maryland, was killed [6]. As the brigade retreated, Lt. Francis Smith voluntarily remained with the body of his regimental commander, and under heavy fire, he brought the body off the field.

Well-read aficionados may point to a 15th Medal of Honor award from the Hatcher’s Run battle. A renowned historian claimed that Chaplain Henry Hopkins (120th New York) received the award [7] for deeds performed during Brig. Gen. Robert McAllister’s stubborn defense against Confederate assaults on February 5. Despite this view echoing in subsequent narratives, Hopkins did not receive an award.

Well-read aficionados may point to a 15th Medal of Honor award from the Hatcher’s Run battle. A renowned historian claimed that Chaplain Henry Hopkins (120th New York) received the award [7] for deeds performed during Brig. Gen. Robert McAllister’s stubborn defense against Confederate assaults on February 5. Despite this view echoing in subsequent narratives, Hopkins did not receive an award.

As of June 2024, the 14 brave Medal of Honor recipients are not mentioned at the preserved Hatcher’s Run battlefield. This oversight could easily be remedied and is no less than these gallant soldiers and their descendants deserve.

Dr. Nigel Lambert is a retired British academic who lives near Norwich, England. He has published many bioscience and social science articles linked to various medical issues. A life-long Civil War enthusiast, he recently became interested in the battle of Hatcher’s Run. Surprised by the sparse and conflicting literature on the battle, he employed his scientific and qualitative research know-how to advance our understanding of the battle. Working with US experts on the Petersburg campaign, he has created an extensive e-library for the battle. Using this database, he has authored two articles in North &South magazine article and five articles on the “Siege of Petersburg Online” website. A book chapter describing the battle is currently under review.

Notes

[1] Only Union soldiers received the Medal of Honor.

[2] The battle has been overlooked in many seminal works. One noted historian claimed, “The battle … finds no conspicuous place in the chronicles of the war.” Freeman Cleaves, Meade of Gettysburg (Norman, OK, 1960), 306.

[3] This action is described in Edward S. Alexander, “Hatcher’s Run 150: Crossing Rowanty Creek” Emerging Civil War Online, February 6, 2015, Hatcher’s Run 150: Crossing Rowanty Creek

[4] The officer rescued may have been a captain or colonel named Harper.

[5] Nigel Lambert, “A Civil War Medal of Honor Mystery,” North & South Magazine (September 2023) Series 2, Vol. 3, No. 6, 88-92.

[6] Colonel Wilson was the most senior Union soldier killed outright at the battle. His brother died in the same engagement.

[7] Robert McAllister, The Civil War Letters of General Robert McAllister, James I. Robertson, ed. (New Brunswick, NJ, 1965), 584, note 14.

Main Sources

Walter F. Beyer & Oscar F. Keydel, ed., Deeds of Valor; How American Heroes Won the Medal of Honor, 2 vols. (Detroit, MI, 1905), 1:479-86.

Congressional Medal of Honor Society, Medal of Honor Recipients Overview and Information | CMOHS.

Nigel Lambert & Bryce A. Suderow, “The Battle of Hatcher’s Run: A Re-Appraisal,” North & South Magazine (January 2022) Series 2, Vol. 2, No. 5, 35-46.

Well written, well told, well done. Thank you very much! Yes, the Medal of Honor awardee’s should be recognized. What a fight!

Thanks for your warm comments. I’ve raised the issue with civil war trails. Hopefully a site board can be erected. I guess the 14 combatants have many living descendants too.