Major General David McM. Gregg’s Final Mission: Three Exhausting Days in the Saddle

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Nigel Lambert

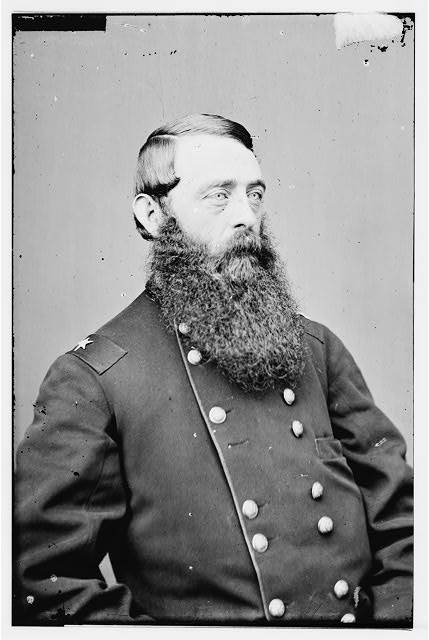

On January 25, 1865, highly regarded Maj. Gen. David McM. Gregg, commander of the Union’s 2nd Cavalry Division, unexpectedly tendered his resignation. What motivated this drastic decision? Army gossip spoke of the allure of his “pretty wife” at home. Some speculated on an unwillingness to serve under Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, soon to arrive in the Petersburg sector. Others linked it to emotional stress and Gregg’s irrational fears of believing he was a coward.

Despite this development, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant still selected Gregg to spearhead his next Petersburg offensive. His cavalry was tasked with destroying a Confederate supply route along Boydton Plank Road around Dinwiddie Courthouse. Major General Gouverneur K. Warren’s 5th Corps would support the raid.

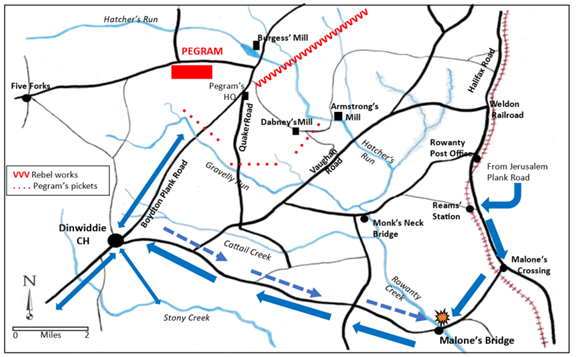

As officials processed his resignation, at 3:00 a.m. on Sunday, February 5, 1865, Gregg led his cavalry (three brigades totaling 6,500 men) out of its camp south of Petersburg toward hostile territory. In bitterly cold weather, the cavalrymen passed Reams’s Station, and with no enemy in sight, they continued southwest toward Rowanty Creek. About one mile from Malone’s Bridge, the Yankees encountered Confederate videttes. The Rebels quickly joined their compatriots (Companies F and H, 13th Virginia Cavalry), occupying a line of earthworks on the opposite side of the creek, dismantling the bridge behind them as they crossed. Rebel Pvt. Oscie Crump recalled how they had nearly removed all the bridge planks when the Federals charged. Upon discovering the bridge was damaged, the Union troopers fell back, but they soon returned. The Yankees managed to repair the bridge and charged over, scattering the Rebels for half a mile across an open field. Crump claimed the Yankees captured six Confederates out of 30 [1].

The Federal cavalry continued west along terrible roads, but met no more Rebels. Upon reaching Dinwiddie (about 1:00 p.m.), Gregg discovered a largely abandoned supply route. Grant’s intelligence underpinning the raid had been inaccurate. They captured 25 army wagons, 100 mules, one Rebel colonel [2], and three other officers. Gregg fanned his troopers out to see what further damage they could achieve. However, these forays added only a few more prisoners and wagons to their meager haul.

With the mission accomplished, Gregg’s goal now entailed safely returning to Union lines. The cavalrymen left Dinwiddie around 3:30 p.m. Gregg informed Warren of his adventures and that he was returning to Malone’s Bridge, where he would bivouac and await further orders. Gregg added, “The roads are so bad that my command can scarcely get along.” About twelve Rebels harassed Gregg’s troopers during their return trip, occasionally firing into their rear guard. No Federals were injured, but two were captured. The weary Federal cavalrymen eventually reached Malone’s Bridge around 10:00 p.m. and bivouacked.

Gregg soon learned he had to move his force to Warren’s new position on Vaughan Road. Imagine his dismay and the reaction of his cavalrymen to this news. They had been on the move in the wet and freezing weather since 3:00 a.m. An officer recalled how they managed to eat and doze for a few hours before moving out into the cold, dark landscape. Menaced continually by Rebel cavalry, Gregg made contact with Warren’s V Corps around dawn (February 6).

As the troopers prepared breakfast along Vaughan Road, dismounted Rebel cavalry (from Brig. Gen. Richard L. Beale’s brigade) vigorously attacked their rearguard. The 10th New York Cavalry helped drive the Rebels back. Joined by the 1st Maine Cavalry, they hastily constructed breastworks across Vaughan Road near the Keys house as the firing continued. Armed with repeating rifles, the bluecoats easily held off the Confederates.

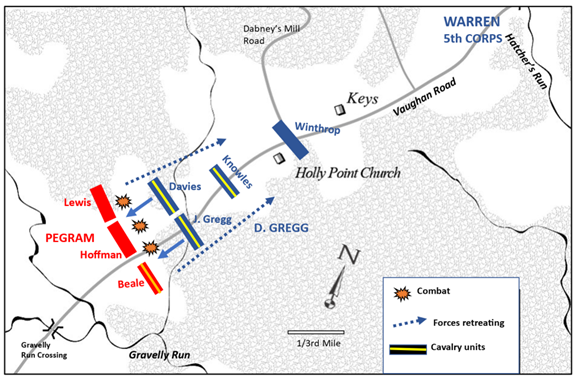

The arrival of Rebel infantry (Brig. Gen. John Pegram with two brigades) intensified the skirmishing and threatened the Union control of the strategically important Vaughan Road. About a mile further up the road, Warren ordered Brig. Gen. Frederick Winthrop’s infantry brigade to support the embattled cavalrymen. They relieved Gregg’s troopers as the skirmishing continued.

Shortly after 1:15 p.m., Warren ordered Gregg to drive all Rebels on Vaughan Road beyond the Gravelly Run crossing. Gregg chose his cousin’s (Brig. Gen. John I. Gregg) brigade to spearhead the assault. Unaware of Pegram’s arrival, the Yankees expected little difficulty driving back a few dismounted Confederate cavalry troopers.

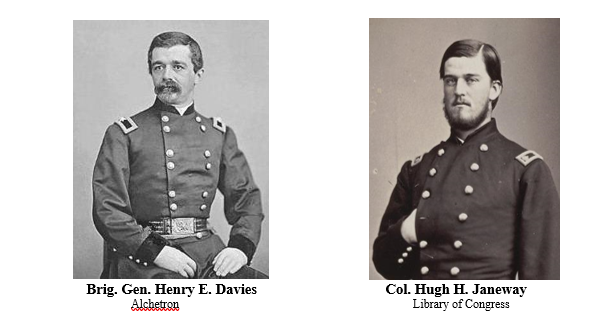

John Gregg positioned his cavalrymen on the road with Brig. Gen. Henry E. Davies’s brigade supporting them on the right and Col. Oliver B. Knowles’s brigade in reserve. The troopers rode down Vaughan Road towards the Gravelly crossing. Federal Maj. Benjamin W. Crowninshield recalled hearing the order “charge” as the horsemen galloped towards the Rebels in rifle pits concealed in woods. The Yankees made several attempts to dislodge the Confederates. Amid the fighting, the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry dismounted and charged some Confederate infantry holding a group of buildings. They reportedly captured around 30 Rebels. To assist his brigade comrades, Col. Michael Kerwin ordered a squadron from his 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry to charge. This mounted assault led by Sgt. Daniel Caldwell allegedly captured 66 Rebels. Amid the fighting, Caldwell took five prisoners and captured the flag from a Tar Heel infantry regiment [3]. However, the Rebel infantry positions proved too strong. Pegram’s Rebels counterattacked, pushing the blue cavalrymen back in disarray.

As one Yankee recalled, “We had an awfully hot time.” The fight proved costly for the Federals in terms of senior officers lost. Brigade commanders J. Gregg and Davies quickly fell with severe wounds. Colonel Hugh H. Janeway, who took over Davies’s brigade, was also wounded. Lieutenant Colonel Myron H. Beaumont fell wounded, and Lt. Col. Frederick L. Tremain was mortally wounded.

Winthrop watched on as Gregg’s troopers charged the Rebels. He reported, “They soon became actively engaged with the enemy’s infantry and, getting rather roughly handled, retired in considerable confusion, the enemy closely following.” Winthrop ordered his infantry forward at the double-quick and delivered some “very fair volleys” into the advancing Confederates. This checked the onrushing Confederates, who withdrew to the shelter of some woods. Once or twice, they reappeared and tried to advance across the open field, “but each time were handsomely repulsed.”

The arrival of further Federal infantry eventually scattered Pegram’s infantry. Elements of Gregg’s cavalry followed the retreating Rebel cavalry until they crossed back over Gravelly Run. Lieutenant Cormany remembered, “Emptying a great many saddles and firing furiously into the fleeing enemy,” Confederate artillery fire from the opposite bank halted the pursuing troopers. By 4:30 p.m., the Federals had vanquished the Rebels along Vaughan Road. With night approaching, the cavalry withdrew to the Keys house, content at clearing the road to the Gravelly Run crossing, as instructed three hours earlier.

Sleep again evaded Gregg’s fatigued cavalrymen. Strong winds, freezing rain, and snow made for a tortuous night. With no protective materials, many kept moving to avoid freezing to death. One recalled how some men “crawled under a tarpaulin and slept.” In the morning, “the tarpaulin was frozen down, and they were relieved only by the careful use of the axe.”

After briefly skirmishing the next day (February 7), Gregg’s weary troopers eventually returned to their warm camps on February 8. They had suffered 117 casualties during the mission. Gregg’s resignation took effect on February 9 with no fanfare or speeches. To the surprise of his troopers, this beloved and influential commander left the service. He was the longest-tenured Union cavalry division commander during the war [4].

Dr. Nigel Lambert is a retired British academic who lives near Norwich, England. He has published many bioscience and social science articles linked to various medical issues. A life-long Civil War enthusiast, he recently became interested in the battle of Hatcher’s Run. Surprised by the sparse and conflicting literature on the battle, he employed his scientific and qualitative research know-how to advance our understanding of the battle. Working with US experts on the Petersburg campaign, he has created an extensive e-library for the battle. Using this database, he has authored two articles in North &South magazine article and five articles on the “Siege of Petersburg Online” website. A book chapter describing the battle is currently under review.

Notes

[1] Inspecting the position at the time, Confederate Maj. Gen. William H. “Rooney” Lee narrowly evaded capture.

[2] The captured colonel was William Clarke (24th North Carolina), who was returning home to convalesce.

[3] Caldwell received a Medal of Honor and a promotion to second lieutenant. The captured flag reportedly belonged to the 33rd North Carolina. Unfortunately, this Rebel regiment was not present at the battle! (Nigel Lambert, “A Civil War Medal of Honor Mystery,” North & South Magazine (September 2023) Series 2, Vol. 3, No. 6, 88-92).

[4] I thank George Skoch for permitting the use of his baseline map and Bryce A. Suderow for supporting my research.

Main Sources

OR 46/1:254-55, 279-80, 365-71.

OR 46/2:409-10, 430, 464-65, 500.

Harold Hand, One Good Regiment (Victoria, Canada, 2000), 190-195.

Benjamin W. Crowninshield, A History of the First Regiment of Massachusetts Cavalry Volunteers (Boston, 1891), 249-50.

Noble D. Preston, History of the 10th Regiment of Cavalry, New York State Volunteers (New York, 1892), 240-43.

James C. Mohr, ed., The Cormany Diaries: A Northern Family in the Civil War (Pittsburgh, PA, 1982), 516-19.

Daniel T. Balfour, The 13th Virginia Cavalry (Lynchburg, VA, 1986), 43.

Edward P. Tobie, History of the First Maine Cavalry, 1861–1865 (Boston, 1887), 378-81.

Edward G. Longacre, Lincoln’s Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of The Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865 (Mechanicsburg, PA, 2000), 322-23.

Thank you! The Union cavalry sometimes get overlooked by JEB’s boys. It’s difficult to image the extreme exhaustion, trauma, and illnesses…and still trying to function in combat. I guess it’s not until WWI when we start seeing combatants focusing on war fatigue: Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Robert Graves.

Thank you. You raise an important issue with PTSD. I don’t think that it was particularly well recognised even in WW1. Living Hell by Michael Adams is an excellent book that covers the stress and misery of civil war soldiers – cannot recommend it highly enough.

Great research work! Thank you for sharing these insights.

Thanks Tim. Grant’s 8th Offensive just keep on giving!

Gregg was an underappreciated and fine cavalry commander. His lack of self-promotion, which should be viewed as a virtue, instead caused him to be a background figure in the war. See Unsung Hero of Gettysburg: The Story of Union General David McMurtrie Gregg by Edward Longacre.

Thanks for your comments. I have the 2000 Longacre book, I’ll check out the Unsung Hero one.

Yes, how history is told is sometimes as fascinating as what happened. How some actors end up in the shadows while others bask in the bright light. Self promotion and media management was as important then as now.