February 1865: When Grant Just Wanted to Do Something

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Nigel Lambert.

As 1865 dawned, Union commander-in-chief Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had reasons for optimism. Major General William T. Sherman’s army prepared to march northward through South Carolina. Federal troops had crushed Confederate forces in Tennessee and the Shenandoah Valley. Wilmington, the last Rebel Atlantic port, was cut off and soon would fall.[1] The Confederates’ main force, commanded by Gen. Robert E. Lee, remained confined around Richmond and Petersburg. Everything had remained relatively quiet there since Grant’s seventh offensive in early December, which disrupted the Weldon railroad as far south as Bellfield. Most accounts overlook or misrepresent the motives and objectives of Grant’s next mission.[2] This article seeks to clarify the record.

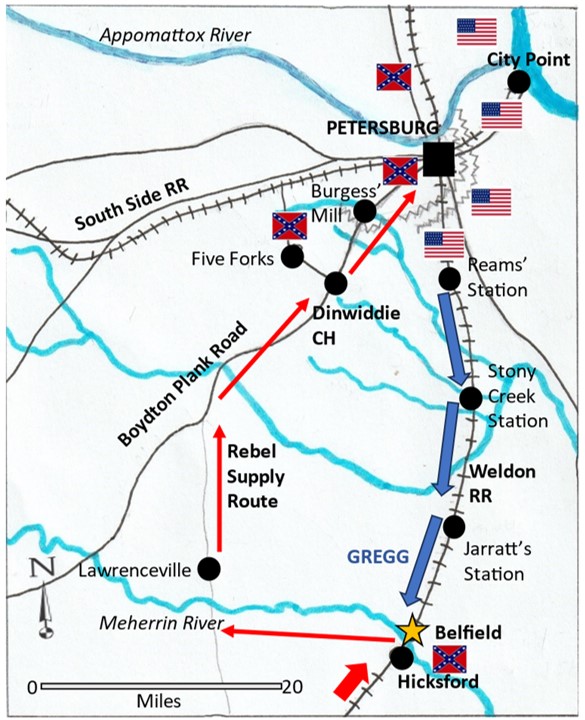

On February 3, a peace conference occurred on the steamship River Queen, moored in Hampton Roads. Although cordial, the negotiations quickly collapsed.[3] As the Confederate delegates returned to Richmond, Grant’s mind switched to a new offensive. With the winter weather temporarily abating, he searched for an opportunity to strike.[4] Intelligence reached Grant that the Confederates unloaded trains laden with supplies into wagons at Belfield and floated them up the Meherrin River to Boydton Plank Road before heading to Petersburg. With this in mind, Grant developed a plan targeting the Belfield Confederate stores.

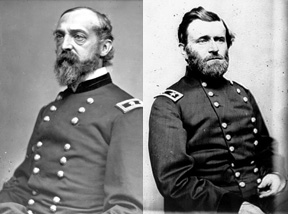

Around noon on Saturday, February 4, Grant explained his idea to Army of the Potomac commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. Grant proposed sending Maj. Gen. David McM. Gregg’s cavalry division on a raid to Belfield to “destroy or capture as much as possible of the enemy’s wagon train, which . . . is being used in connection with the Weldon railroad to partially supply the [Rebel] troops about Petersburg.” An infantry corps would travel towards Stony Creek to support the cavalry. Grant wanted the cavalry to move out at 3:00 a.m. the next day if possible. To maximize speed, they should take no wagons, few ambulances, and minimal forage and rations. Similarly, the infantry would travel lightly, with accompanying artillery kept to no more than one battery per division.

After lengthy reflection, at 4:30 p.m. Meade wrote to Grant proposing a substantive modification. Rather than sending Gregg’s cavalry 40 miles south to Belfield, Meade suggested they move south for ten miles before heading west to Dinwiddie Court House on Boydton Plank Road. He reasoned they could intercept Confederate supply wagons there just as easily as at Belfield. The V Corps would march to the western end of Vaughan Road to support the cavalry. Two II Corps divisions would move a few miles southwest and take up positions on two Hatcher’s Run crossings. Here, they would block Confederate forces in their works defending Boydton Plank Road from moving out and cutting off any Federal troops from the main Union lines.

Meade’s plan retained the same objective as Grant’s initial idea, but involved traveling shorter distances with the three forces remaining closer. This reduced the chances of the Rebels isolating one of them. Furthermore, a Confederate cavalry division known to be around Belfield would have a greater distance to cover to trouble the Union forces.

Acutely aware of public backlash to failed military operations, Meade asked Grant, “Are the objects to be attained commensurate with the disappointment which the public are sure to entertain if you make any movement and return without some striking result?” This also hints at Meade’s skepticism regarding the mission’s value. At 6:45 p.m., Grant replied to Meade, agreeing to all the changes and assuring him, “The objects to be attained are of importance.” Grant promised to telegraph Washington in advance, revealing the mission’s objective. The subsequent operation reports, he claimed, would satisfy the public.

An hour later, Meade messaged Grant, saying, “The orders are all issued; the cavalry will move at 3 a.m. and the infantry at 7 a.m.” He relayed news that a Confederate cavalry division had departed for North Carolina, thus leaving only one Rebel cavalry division to oppose Gregg. Encouraged by this information, Grant again pushed his original Belfield idea. At 8:30 p.m., Grant asked Meade, “If Gregg can possibly go to Belfield, he probably will be enabled to destroy a large amount of stores accumulated there. The departure of one division of the enemy’s cavalry will favor this.”

Meade tactfully replied to Grant, saying he had now ordered Gregg to proceed to Belfield, provided he found reliable intelligence suggesting that he could achieve anything there upon reaching Dinwiddie. Meade pointed out that the Rebels would store any accumulated supplies at the Hicksford depot on the other (Confederate) side of the Meherrin River from Belfield. Furthermore, Rebel artillery protected the position, as Union forces had discovered in December 1864. Meade added, “We also believe that W. H. F. [Rooney] Lee’s cavalry division is in that vicinity. Gregg goes without artillery.” Thus, while not directly opposing his superior’s desire to strike at Belfield, Meade effectively killed the idea through sound reasoning. At 10:00 p.m., as promised, Grant sent a dispatch to Washington explaining the proposed mission. The Union’s eighth Petersburg offensive was about to commence.

Grant’s Belfield plan appears rushed and reckless. A similar Union force had ventured there less than two months earlier. They had found Belfield well-fortified and defended by artillery positioned at Hicksford across the river. The Federals had deemed the position too formidable to attack and withdrew. This proved a wise decision as a Rebel force headed for their rear. Yet, despite this recent experience, Grant proposed a similar venture.

As Meade pointed out, it is doubtful that Gregg’s cavalry could have captured Belfield without artillery, and the Confederates would have stored wagons/supplies safely at Hicksford. Furthermore, Rooney Lee’s cavalry division had recently joined the small Rebel force and artillery guarding Belfield, a fact known to the Federal high command. This force would have proven a sizeable foe for Gregg’s troopers. If Meade had followed Grant’s original plan, Gregg’s cavalrymen could have met with calamity.

As overall commander, Grant could have insisted that Meade carry out his Belfield plan. However, he wisely allowed Meade to moderate his ambitious plan. The revised idea of intercepting the Rebel supply line around Dinwiddie entailed fewer risks. Yet, it still involved endangering nearly two army corps (about 28,000 men) supporting a cavalry raid of 6,500 troopers. The II Corps had to secure two probably well-defended strategic crossings of Hatcher’s Run. Meade voiced concerns that such a large-scale offensive needed to garner substantial achievements to appease the public and politicians. There is the suspicion that Grant could claim credit for any successes while having Meade available as a scapegoat for failures.

Ultimately, Gregg’s raid found a mostly abandoned supply route, rendering the mission’s stated objective meaningless. Grant’s intelligence had been inaccurate. The raid triggered the three-day battle of Hatcher’s Run, which cost Grant over 1,500 casualties. The supporting infantry twice came close to disaster, but they captured and retained two crossings of Hatcher’s Run. This enabled the Union to extend their lines three miles further west. The Northern press (with Grant’s blessing) hailed the mission a tactical success, writing how Grant’s offensive to threaten the Southside Railroad had moved the Union lines closer to that essential Rebel artery. This narrative conveniently used the mission’s outcome to define its goal, a pretense that has echoed down the decades. This article reminds us that Grant’s original plan was a cavalry raid to Belfield. Even his revised mission didn’t aim to extend Union lines.

Grant’s memoirs and papers overlooked the offensive, noting that around Petersburg, “the winter passed off … uneventfully.” They do reveal that his greatest fear was Lee’s army slipping away. After six weeks of inaction, this fear probably motivated the offensive. Grant was desperate to keep Lee occupied and prevent him from sending troops to fight Sheridan or Sherman.[5] For Grant, the specifics of the mission probably weren’t critical; with his restless personality, he simply wanted to do something.[6]

Dr. Nigel Lambert is a retired British academic who lives near Norwich, England. He has published many bioscience and social science articles linked to various medical issues. A life-long Civil War enthusiast, he recently became interested in the battle of Hatcher’s Run. Surprised by the sparse and conflicting literature on the battle, he employed his scientific and qualitative research know-how to advance our understanding of the battle. Working with US experts on the Petersburg campaign, he has created an extensive e-library for the battle. Using this database, he has authored two articles in North &South magazine article and five articles on the “Siege of Petersburg Online” website. A book chapter describing the battle is currently under review.

Main Sources:

Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of General U. S. Grant, 2 vols. (New York, 1885), 2:439-40.

John Horn, The Petersburg Campaign (Cambridge, MA, 1993), 182-200.

The War of the Rebelliion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 46, Part 2, 366-72, 377-78, 380-81, and Series 1, Vol. 42, Part 2, 1092.

Endnotes:

[1] The capture of Fort Fisher on January 15 effectively cut off Wilmington, preventing its ability to supply the Confederacy. The city eventually fell into Union hands on February 22.

[2] See, for example, Noah A. Trudeau, The Last Citadel (Baton Rouge, LA, 1991), 312; A. Wilson Green, The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign (Knoxville, TN, 2008), 101; The Petersburg Progress-Index, Siege Centennial, Part 36, “Another Battle, Another Warning,” February 5, 1965; William A. Frassanito, Grant and Lee: The Virginia Campaigns, 1864–65 (New York, 1983), 332.

[3] President Lincoln, with Secretary of State William H. Seward, met with three Confederate peace commissioners: Vice President Alexander A. Stephens, Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell, and former Confederate Secretary of State Robert M. Hunter.

[4] February was notoriously bad for launching Virginia offensives; road conditions made large troop movements extremely challenging. The ensuing battle around Hatcher’s Run was the only substantive Civil War action in Virginia during a February.

[5] Testimony from two senior Union officers supports this assumption: Emerson G. Taylor, Gouverneur Kemble Warren: The Life and Letters of an American Soldier, 1830–1882 (New York, 1932), 203-04; Joshua L. Chamberlain, The Passing of the Armies (New York, 1915), 32-33.

[6] Thanks to Bryce Suderow for supporting my research.

Grant was blessed with a skilled military politician’s ability to selectively forget about or restate the inconvenient. His Memoirs are a masterpiece of the “Gee whiz, little old me?” school of special pleading.

Thanks for your comment John. I’m no expert on Grant per se, but from what I’ve read, I do get the sense that he was very good at media manipulation,and I’m not sure where in his background he developed such a skill. He does seem to be a character, folks still have strong views about, one way or the other. From the other recent ECW post this is the time of year around his death, which was a coincidence on my part. Makes for a timely theme.

What I find interesting about this article is the fact that there was concern over what the public would think. I need to look more into this because the slow movements of the winter were a result of Lincoln’s reelection. There was no need to persuade the public anymore the war was going well. There was also no need to rush results since he had won. Grant was trying to preserve manpower. it is very much like Grant to listen to all options and consider the best course of action. It was rare that his spy network was wrong, but even in that case, Grant still managed to make dividends off his actions. Look at the extension of lines and greater loss of Confederate forces. Furthermore, in a report back from Meade dated on 5 February, he provides Grant information on what Gregg was able to obtain from his raid. He reported the following,

Gen Gregg was ordered to move to Dinwiddie C H & move up & down the Boydton Road to intercept & capture the Enemys trains & was further ordered to determine whether or not he could in any way inflict damge upon the enemy…Gen Gregg proceeded to Dinwiddie C H & moved up & down the Vaughan road & captured some 18 wagons & 50 prisoners including one colonel—Finding that the Boydton road was but little used since the destruction of the bridges on that road & on the Weldon RR he returned to Malones bridge on Hatchers Run.

Gregg later connected with Warren during the battle.

Nigel,

Somehow, through all his pre-war career, he’d developed the ability to pick his moment, and outlast his enemies, real or imagined. His greatest service to the Republic was in convincing his fellow Midwesterner, Lincoln to largely keep his hand out of military matters. This was no mean feat given the appalling bloodletting of May and early June 1864. No other commander had that skill in placating the President. The latter even gave him remarkable latitude in disposing of generals Lincoln had once thought politically indispensable.

Great post as it shows the interaction between commanders when planning an operation and what they make of it after. The battle seems like a draw in the end.

No. At the operational level, Grant lodged his men into the ground further west holding a better position against Petersburg. Tactically, Warren drove Confederates back from Dabney’s Mill they had lost the previous ending the battle. If you measure tactics by casualties, the Union still come out ahead. Even though the Union lost 1500 that was only 4% of used manpower. Meanwhile, the Confederates lost 1200. That made up 9% of total casualties. Therefore, it was another decisive blow to the Confederates at Petersburg.

Thanks for your response Nate, I’m loving the discussion. We seem to be reaching our final positions.

1) “Offensives” is the typical word that’s come into parlance as you say. I don’t have a problem with it, seems to convey the actions reasonably enough. I may be wrong but I think that there was some issue with the numbering once upon a time, but now folks seem to have settled on a version.

2) As I said previously, the fighting moved back and forth at Dabney’s Mill during the afternoon of Feb 6. The site changed hands 3-4 times. And you are correct that this was where Pegram perished. I wrote an article about this not so long ago Emerging Civil War . It’s only brief of course, lots of controversy there too! I have a more detailed account coming out in due course. But the Rebels secured the site late on Feb 6, reinforced it overnight, and comfortably held it to the end of the battle, i.e., late Feb 7.

3) Thanks for sharing the Lee story during the Overland Campaign, I did not know that, very interesting and useful story. We can at least agree that Confederate casualty data are challenging. I don’t disagree with your comments on 3:1 attacker ratios etc. My point there was about the limits of using %ages as a metric of “success” particularly in “multi-action” battles. Let’s say Union force A (5,000) attacks Rebel force B (2000) – A gets routed, they lose 300 men, force B loses 100. The next day a different Union force C (5,000) launches another attack on the same Rebel force B (now 1900). Again, the Union are routed losing 300 men as the Rebels again lose 100 men. During the two-day battle the Union force has been routed twice. Yet their combined force of 10,000 (A+C) suffered 600 casualties (6%). the Rebels meanwhile had 2000 men at the battle, and lost 200 i.e 10% casualties! Deciding who “won” on %ages seems rather moot. Of the 43,000 Union troops at Hatchers Run not all fought at all the mini-battles. The II Corps for example only really fought on Feb 5. Most of Warren’s V Corps didn’t fight on Feb 5. Whereas some Rebel units fought on all three days.

4) Irrespective of any claims to “reasonableness,” it’s a matter of record that Meade did worry about public and political opinion regarding the 8th offensive. Whether he was super-sensitive, neurotic, overly stressed or just liked having his back covered, one could argue over underlying personalities for ever. Probably why no two biographies of the same person are the same. In my article, I do make reference to Grant’s “restless personality” for example. I don’t have any psychiatric data to back that up, but going on what I’ve read and heard I didn’t think that was a too controversial view. And if a few folks disagree, so be it – “cannot please everyone all the time.” If however, most reviewers said that view was well out of order and gave reasons, then I’d obviously adapt accordingly.

5) I did allude to the change of plans halfway through the battle in my reply, which enabled the extension of the Union line. And you are right in that on the evening of Feb 5, Grant proposed for Meade to advance on Burgess Mill and threaten the SouthSide railroad. What you failed to mention was Meade’s reply showing the improbability of such a move (OR 46/2:389-90; OR 46/1:150). One could view that as another example of the on-site Meade reining in the more distant Grant’s ambitious (dare I say reckless) plans. I think where I take a serious issue with you is in the notion that Grant was somehow able to foresee the consequences of the mission from the start! That’s just patently absurd. There were so many twists and turns during the 3 days, simple twists of fate, near misses and what-ifs. All sorts of scenarios could have occurred. I don’t think any general goes into battle knowing what’s going to happen. Hindsight is perfect. As my article pointed out, many accounts have taken what happened and projected that onto the initial plan, That seems to be the nub of the matter for me.

6) Do you have the OR reference at all? I wasn’t aware that Grant wanted to divert Rebels forces (which ones?) to Belfield?

I thank you once again for your interest in my article. you’ve certainly provided food for thought. I don’t know if you saw my other 6 articles on the battle / offensive. Or was it “Grant” that drew you in?

Thanks for your comment Sean. Turns out it’s the anniversary of Grant’s death so good timing on the editor’s behalf.

Yes, the messages passed between Meade and Grant are fascinating. As senior commander Grant could have insisted that his Belfield raid was carried out, but he did accept Meade’s comments / concerns which showed wisdom, as his initial idea was very reckless and could have put Gregg’s cavalry in serious peril.

Rating the battle’s outcome is rather complicated and nuanced I feel. At one point the Battlefield Trust had it down as a Union victory, but it’s now marked as a draw when last I looked. In terms of achieving its original goal, the mission was a failure as the supply route Grant wanted to destroy was abandoned. However, the Federals certainly gained some positives from the 3 days – notably extending their lines 3 miles further west, securing the two Hatcher’s Run crossings and keeping Lee’s army busy, draining it further of soldiers and encouraging many to desert. The desertion rate in the ANV significantly increased after the battle. The Confederates didn’t get much out of the battle, other than they survived to fight another day. They messed up a chance to inflict serious damage on the II Corps on Feb 5 and were unlucky in not being able to inflict more damage on the V Corps who got routed late on Feb 6.

I have to disagree that Grant’s plan was “reckless.” Grant utilized the Second and Fifth Corps to support the cavalry raid. Which would consist of somewhere between 16000 men with artillery support. It purpose was not to stay and hold the place but simply wreck Confederate logistics further depleting their supplies. It was quite unlikely they would get cut off considering the Confederates had to navigate three creeks and supply themselves to stop the raid which they were already short on supplies at the time (food more than anything). Also, the weather had cleared up so Grant saw this as a good opportunity to move. Finally, the Stony Creek raid was successful in December and Grant sought to do something similar. What is brilliant about grant’s ability to read plans and the terrain is after reading Meade’s plan, he saw beyond a simple raid and knew he could make a lodgment further west; this was Grant’s coup d’oeil at work. Grant had a right to trust the BMI as they successfully traced Confederate forces from the Shenandoah to Petersburg. Therefore, Grant was optimistic that supplies were located. However, Grant also recognized that he was general-in-chief and knew Meade still held command over the Army of the Potomac. He identified operational and strategic targets. Meade’s comments about “public perception” are a bit tone deaf considering Lincoln won reelection. Even though there was not supplies as the BMI originally reported, the “raid” paid dividends and Grant knew it would.

In response to the comments above,

1) I agree with largely what you said. Do I like the term “offensive?” No, because no one referred to them as that, but that is more of the byproduct of historiography over time.

2) For some reason I thought the line extended further back beyond Dabney’s Mill, and I thought the picket line was at Dabney’s Mill. But did not the Confederates try attacking Warren’s position and equally failed in the attempt when Pegram was killed?

3) As far as numbers are concerned, I spent a considerable time dabbling with them writing about Cold Harbor. I utilized Young’s work for that. You are right there are problems with Confederate data. That is why I listed 1200. I have seen that casualty listing as well, but if you refer back to Lee’s orders before the Overland Campaign, he told his officers not to record casualties unless they were “seriously wounded.” I found one account at Cold Harbor where a soldier was shot through the cheek and it was not recorded. Therefore, it is safe to say that the Confederates probably suffered more casualties than previously listed.

As far as the Union “far outnumbering” the Confederates, military doctrine dictates that you possess a 3:1 advantage over the defender if they are behind entrenchments. It is likely the attacker will suffer a higher ratio of casualties as a result. That is why Grant’s campaign in Virginia is so unique because he suffered fewer casualties on a ratio basis.

4) IMHO it was unreasonable of Meade to worry about the public perception of him. Grant came to his defense in every instance. Even when Grant arrived to DC in 1864, he came to Meade’s defense when political leaders inquired as to why he did not pursue Lee. Grant defended his actions at Spotsylvania, and saved him from the press again at Cold Harbor.

5) I would not call it “wisdom” but “adaptability.” It is rare for a commanding officer to take the ideas of a subordinate and utilize them as his own. Secondly, it was a “raid.” The Applejack Raid was not supposed to connect with Grant’s forces. The definition of a raid from the United States Military is as follows, “A raid is a surprise attack against a position or installation for a specific purpose other than seizing and holding the terrain.” Warren did manage to destroy the railroad and could have just as easily have cut off Confederate forces with Potter’s relief on arriving. It would’ve been impossible for the Confederates to cut off and destroy Warren’s entire corps. By this point in the war how often was a corps completely destroyed or captured on the battlefield? Only Grant had successfully done it up to that point.

You already mentioned that Grant focused on speed of the raid by providing the appropriate rations and no wagons. He even provided a relief force much like Potter was to Warren during the Applejack Raid. Grant always thought of contingency plans because von Moltke the Elder said that plans go out the window on the point of contact with the enemy. Grant knew that better than anyone.

Let’s talk for a minute about the definition of coup d’oeil. Developing a good plan is not the gift of a coup d’oeil (refer to Moltke’s quote). The glance of an eye is the ability in a single moment to see a new possibilities. It often comes in the heat of battle or in a single moment, not over the course of a day or week. Such was the case on 5 February (which I understand is outside the scope of the article for which I should have provided more clarification), Grant sent the following order to Meade, “Your dispatch of 6 45 just recd. Bring Warren & Cavy back & if you can follow the enemy do it ?If we can follow the enemy up although it was not con[tem]plated before it may lead to getting the south side road or a position from which it can be reached Change original instructions to give all advantages you can take of the enemys acts.” Therefore, Grant did mention the land grab at Hatcher’s Run in the ORs. In this moment Grant saw the chance to get at the South Side Railroad and sure enough after this offensive he held ground that was a launching board to it. The results of the campaign clearly was not “unforeseen” by Grant.

6) Finally, as a last note, Grant offered up the chance to go to Belfield again because he wanted to divert Confederate forces there as mentioned in the ORs.

Thank you for your stimulating comments, Nate. I’m always thrilled to witness discussion on this mostly overlooked battle, even if it is via General Grant’s bright light.

You have raised several important points that I will try and expand upon.

1) As I replied to Sean, I would agree with you that extending the Union line three miles further west was a notable gain from the offensive. This not only further stretched Lee’s thinly manned defensive line, but it provided a better launch pad for the “Appomattox Campaign.” The offensive also kept Lee and his army occupied. Grant’s memoirs and the letters of Warren and Chamberlain, support the view that this was the main driver of the 8th offensive. The fact that it is also consistent with his “restless personality” is supporting circumstantial evidence. The offensive drained the Rebels of officers and men it could ill afford to lose. Crucially, it encouraged many in the Confederate ranks to desert – this is neatly quantified in eg John Horn’s Petersburg Campaign book. There were few, if any Rebel gains from the offensive – other than survival and giving the Union force a bloody nose. So, in terms of overall gains, one could say that the Union “won” the battle.

2) Just to correct a possible typo in one of your responses – on February 7, Crawford’s division (Warren’s V Corps) drove the strong Rebel picket line back to their Dabney’s Mill line (which they had strengthened overnight including positioning artillery there). This they achieved by the late afternoon during a winter storm. Contrary to orders Warren then ordered Crawford to storm the Rebel defenses at Dabney’s Mill. This predictably failed miserably. The assault was called off and the battle ended. But Warren did not push the Rebels back beyond Dabney’s Mill. Fighting had moved back and fro from Dabney’s Mill the previous afternoon, but the Union had never secured the site.

3) Numbers are often a slippery concept. I’m thinking of writing an article about the “numbers” from the battle and the problems entailed. So, with a “spoiler alert” I’ll just say that your numbers are roughly correct. The use of percentages is tricky. As the Union had about three times more men than the Rebels, their losses would be relatively smaller as a percentage, especially as this was not one pitched battle, but a series of smaller battles. “Used manpower” is a complex term – do we include or exclude Hartranft’s division (3,200) who although sent as reinforcements, didn’t partake in any combat per se? The real problem comes with the Confederate data! Some argue that Rooney Lee’s cavalry division was present, I would suggest that only one brigade made the fight. Some memoirs suggest that Philip Cook’s Georgia brigade took part in the February 5 fighting – I’d label that as “tentative”. Confederate casualties are a real nightmare. My colleague Alfred Young has done an excellent job in compiling such tricky data – but I’m sure he would be the first to say that his data are not absolute. The large number of “informal” desertions is not recorded, beyond those who handed themselves in to the Union forces. You claim 1,200 Rebel casualties – the “normal” estimate is 1,000 (from Kyd Douglas’s estimate, which seems to have stuck). I was wondering where you got your estimate from?

4) Public and political concerns were certainly uppermost in Meade’s mind and are noted in his OR letters. My interpretation of this (from reading about Meade) is that Meade was very wary (with reason) of public and political backlash to military actions that didn’t show any tangible benefits. He felt that blame came his way and not Grant’s.

5) Where our views mostly deviate are as follows. I stand by the view that Grant’s Belfield raid idea was reckless, mainly for all the reasons Meade gave (as presented in my article) and the fact that Grant agreed with the changes. For me, this shows Grant’s wisdom. The December “Applejack” offensive had reached Belfield, found it secure (even before Rooney Lee’s cavalry division was based there) and only due to slowness from the Rebels, the Union force nearly got cut off. I see no evidence to support the opinion that Grant’s “coup d’oeil” saw all along that Meade’s plan would allow the extension of the Union lines. That seems to be apportioning credit where none is due. Opponents of such generosity would argue that if this was his cunning plan all along, why didn’t he present it himself, rather than his Belfield raid? His aims for his 8th offensive are quite explicit in the OR, and there is no mention in his plans of any “land-grab.” It is true, that halfway through the battle, Grant and Meade decided to secure the two Hatcher’s Run crossings (which enabled the line extension). The Union had held these crossings before but never attempted to secure them. We probably will agree to disagree but from my reading of the testimony – Grant hastily (within hours) came up with an offensive (the 6th offensive took five days of preparation) mainly to occupy Lee. His plan wisely got changed. The resulting offensive led to particular ad hoc, unforeseen gains (along with a couple of narrow escapes that the Union downplayed). To claim that the gains were always part of Grant’s original cunning plan feels to me a stretch too far to take.

6) If such debates help to put the Battle of Hatcher’s Run back into Civil War consciousness then hurrah for that!

While all the interactions between Grant and Meade were not as positive as this one apparently was, the article clearly demonstrates that Grant and Meade had a constructive and effective working relationship, they shared a strategic perspective, and Grant definitely respected and had confidence in the judgement of his subordinate, General Meade. It also shows that Meade understood and supported Grant’s intentions, and he took time to consider and develop alternatives to make Grant’s concept have a greater probability of being successful. While Grant may have “simply wanted to do something”, the action was a valid initiative strategically, that was consistent with Grant’s desire to destroy Lee’s army and its ability to conduct war. The offensive action placed more stress on the Confederates and forced them to further expend their limited and dwindling resources. Excellent article.

Thanks for your comment David. Glad you liked the article and thanks for indulging my “provocative title,” as this battle has been starved of publicity for decades, I find myself using whatever “hooks” I can to foster awareness.

I agree, the relationship between Meade and Grant seems very interesting, I’ve read a few books on both Grant and Meade which shed some light. I don’t know if there is a book explicitly looking at their relationship. My armchair understanding is that initially Meade felt humiliated at his position of having an army but not really being in command. He thought of resigning. But I think their relationship grew and there are several examples of where Grant was supportive – he came to his aid with the Inquiry into the Crater debacle, he helped sort our Meade’s promotion in Jan 65, which had got delayed. Other issues I’ve read, which are probably conjecture (I’m no expert) is that Meade was a useful “buffer” to Grant, in terms of the infighting and bickering that plagued the AoP and if battlefield events went awry, apportioning blames was more defuse – shall we say. As you will see from the insightful comments above (and on civilwartalk forum) this latter notion is strongly refuted by some.

Many thanks for this thoughtful analysis on Hatcher’s Run and post-mortem on the intelligence that set this engagement in motion … I also appreciated reading the back-and-forth between Grant and Meade … it says a lot about both leaders and their relationship.

What I read was a textbook example of turning time sensitive, actionable intelligence into a military operation involving over 40,000 soldiers and horsemen — all planned and executed in about 18 hours … Grant and Meade had a healthy exchange over how to accomplish a somewhat reduced mission at significantly less risk … the two quickly came to a meeting of minds with Grant acceding to Meade’s recommendation with the caveat to take the Belfield log-hub if possible … again, an exemplar of a well-oiled staff and two generals with a good working relationship.

In terms of Hatcher’s Run being a win or loss, I believe the better question this late in war is did the outcome of this fight support Grant’s strategy to keep pressure on Lee and inflict losses on ANV the south could make good … the answer to that is clearly yes.

Thanks again for this great essay – really enjoyed it.

Thank you Mark for your comment, glad you liked the article. Regarding your final paragraph, I could not agree more. Very succinctly put.

Good stuff, very captivating as always! Interesting to read about the politics underlying the battle and to get an insight into the nuances of the relationship between Grant and Meade. I feel like this also gets to some fundamental essence of war – bored men in power with lots of weaponry at their disposal! Also makes you feel for all the soldiers who are sent on missions like these for no clear reason… at least its better now! oh wait..

Thanks David.

I think the premise of the article, that for some reason the gains from the action are less creditable because Grant originally wanted a cavalry raid, seems a little petty. Actions in war rarely go exactly as originally planned. Great generals see opportunities and exploit them. Grant messaged Meade on the 5th to basically scrap the original plans and take advantage of the situation: “If we can follow the enemy up, although it was not contemplated before, it may lead to getting the south side road or a position from which it can be reached. Change original instructions to give all advantages you can take of the enemys acts.”

Thanks for your comment RB. I think that I’ve covered much of the issue you raise in my latest reply to Nate. I think everyone can agree that the offensive resulted in tangible gains for the Union. How much “credit” for those gains should go to Grant, Meade or serendipity seems to be moot and from the reaction to the issue both here and elsewhere, kind of depends on ones attitude towards Grant as a US icon. For me, I wanted to highlight the common fallacy that extending the Union lines west, was the initial plan all along. It wasn’t even the aim of Meade’s plan B. I also wanted to point out that Grant’s initial Belfield plan was flawed/reckless – somantics of ones choosing. The reasons behind such a conclusion are provided in detail by Meade in the OR. Plus Grant went along with Meade’s assessment. I didn’t particularly see this as controversial, not every idea Grant had was great.

As you correctly point out (as indeed have I in my comments above) battle plans usually change upon contact with the enemy. The Union had captured the same two Hatcher’s Run crossings on at least two occasions previously. The decision – endorsed by Grant – to hold them this time enabled the line extension. I guess as ultimate commander-in-chief one can give all the credit to Grant for this endorsement. It’s not really central to my article. For what it’s worth, to me it seems a bit like a soccer manager taking the credit when one of his players scores a penalty. With the many twists of fate and chance events that did or did not occur during those 3 days one can also wonder where the blame would have landed, if the story had had a bad ending for the Union.

Regarding the “scrap the original plans” story – I dealt with that in my response to Nate – it’s perfectly true, it’s in the OR. What is also in the OR is Meade’s response (citations given in my response to Nate) indicating that the move Grant proposed was not feasible.

What I find pleasing about all the comments raised is that I don’t think there has ever been so much ink spilled on the origins and outcomes of the Battle of Hatcher’s Run. I would argue that it’s long overdue, something we can hopefully all agree upon.

Nigel,

I countered those points following your response. I also quoted the ORs. No, not every single one of Grant’s ideas was great. In fact, I recently wrote an article about his failure during the Battle of Raymond. Nevertheless, the Richmond-Petersburg Blockade is still one of the few operations written about that still dabbles in Lost Cause rhetoric towards Grant. It is rare that I see Grant complimented by many historians during this campaign, which surely raises a few eyebrows. In fact, excluding the biographies of Grant written in recent years, there are only two recent histories that give Grant any credit to this operation. It could be I am not thinking of some, but those I have read, only two come to mind. Unfortunately, words like “delusional” have been thrown around in recent years talking about Grant’s generalship during this period.

I also find it a bit hard to compare it to the roles of a soccer manager and his players. The roles of military officers include a hierarchical structure that are widely accepted by even the lowest ranking soldier. From veterans and soldiers I have talked to, they recognize credit given to superiority officers despite them not being present on the field. Secondly, Grant could have been in Washington D.C. the entire period of 1864-1865 if he so wanted to. There was nothing in his job description that he had to be with any army. Halleck never is chided for it nor McClellan. Even Sherman told him that the glory rested with the Army of the Tennessee. Yet, Grant knew the AotP needed him along with the Army of the James.

I don’t understand why a cavalry raid against enemy supplies would be considered “flawed” or “reckless.” The purpose of a raid is not to capture and hold a place. And I don’t read Meade’s responses to Grant as saying that a cavalry raid would not be “feasible.” I read the exchange between Grant and Meade merely as working out the best options to proceed.

hi RB, thanks for your query. I feel the posts are starting to go around in circles here and mixing many topics. But as you’ve raised one specific issue, and as I’m curious to know what wording you’d suggest, I’ll give it just one more try.

The specific idea I considered flawed or reckless was Grant’s plan to raid the enemy supply base at Belfield. My reasoning for this assessment comes from the OR and Meade’s own objections:

a) Grant first mentioned the Belfield raid to Meade around noon on Feb 4. Ideally, he wanted the raid (plus support from two infantry Corps) to start the following morning. Clearly, unlike before his other Petersburg offensives, Grant had not discussed the offensive at length with his army commander. He seemed to be in a hurry for action. Also, it’s important to state that Grant’s proposed “cavalry” raid (as with the actual action that occurred) was not just a simple cavalry raid, it also involved two infantry corps to act as support.

b) Belfield is 40 miles south of the Union works into potentially hostile territory. That is a long way to travel and runs the real risk of ambush, hence the need for significant (40,000 infantry) protection. Even in Meade’s less risky plan, the II Corps got attacked and but for random events could have been badly mauled.

c) The roads there in February were predictably in a bad state. Gregg constantly complained about the roads when they did march a far shorter distance on Feb 5. He said it was hard for his troopers to travel. How long would it have taken them to get to Belfield and back on such bad roads?

d) Grant was keen to exploit some improved weather, this may explain why he was in a rush? However, February was well known as not a great time to plan mass army movements. As my article says this offensive was the only major action in Virginia in a February during the war. Unsurprisingly the better weather didn’t last long and Feb 6-8 were terrible. Especially Feb 7, when there was a winter blizzard. That would only have negatively affected Gregg’s progress to and from Belfield.

e) The previous offensive in Dec by a larger Federal strike-force had shown that Belfield was well-defended, including artillery across the river at Hicksford. Since then, Rooney Lee’s entire cavalry division was now based there, a fact known to Union command. As Meade pointed out, it’s fairly unrealistic to expect Gregg’s cavalry (without any artillery) to occupy Belfield.

f) Even by some miracle if Gregg had captured (temporarily, as you correctly point out) Belfield, any supplies the Rebels had there would be safely stored on the Rebel side of the river at Hicksford; as Meade pointed out.

g) In summary, Grant’s idea would have thrust two infantry corps and Gregg’s cavalry on a mission using bad roads, 40 miles deep into enemy territory, in harsh weather with a minuscule chance of destroying any Rebel supplies.

All the above is a matter of record. So, I’d be interested to know what adjective you’d use to describe such a plan? Even the most die-hard Grant fan must recognize it as containing flaws – or may be not?

The final judgment on the idea comes from Grant himself. When Meade challenged his plan, Grant immediately acquiesced. As Commander-in-Chief he could easily have insisted that Meade carry out his Belfield raid. I’m sure you’d agree that Grant wasn’t prone to being bullied or coerced by Meade. It seems to me that Grant wasn’t that wedded to the idea and was more interested in undertaking some action and the sooner the better. Grant’s desire for action was understandable and alluded to in Grant’s memoirs and other officer memoirs as my article mentions.

As a consequence, Grant instantly agreed to Meade’s revised plan in full, he made no revisions on Feb 4. I see that as wise generalship on Grant’s part. But even that conclusion hasn’t sat well with some Grant fans (here and elsewhere), which I find weird.

I have never said that Meade’s revised raid to Dinwiddie CH was reckless or flawed or that Meade objected to any cavalry raid per se. Meade’s plan was demonstrably sounder and less risky. It’s probably fair to suggest that Meade was lukewarm about his own idea, but that’s not central to this narrow comment.

I don’t think I can clarify the position any better. Of all the things I’ve written over the years, I didn’t particularly view the above as that controversial. I’m just relaying what’s in the OR. If suggesting that Grant had a bad idea that he chose not to act on is unacceptable to some, then so be it. One can’t please all the people all the time.

A 40 mile cavalry raid is not inherently reckless or flawed. Griersons cavalry raid went 600 miles. Look at Sheridan’s operations. And a cavalry raid is just a cavalry raid. It’s not necessarily an offensive, so the “rushed” and “hurried” descriptions seem off. Grant didn’t order Belfield to be captured or occupied. His stated purpose was to break up the enemy’s wagon train as far as possible. And Meade’s replies to Grant don’t seem a challenge as much as they seem to be suggestions on better options. So I guess I just don’t understand, or agree with, your characterizations of these events.