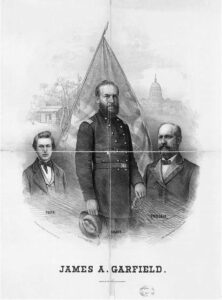

James Garfield’s Presidency Part 1: Nomination

In the closing minutes of Shiloh, two future presidents found themselves at the front lines. One was Ulysses S. Grant, the hero of Fort Donelson. In the early afternoon of April 7 he personally directed a charge at Review Field that many falsely credited with breaking the Confederates. Meanwhile, James Garfield pressed his brigade forward. Garfield never came to grips with the enemy, only being briefly engaged in Rea Field in the battle’s closing minutes. For Garfield, it was his only experience leading troops in a major battle, and it was disappointing.

Shiloh did little to enhance the reputations of Grant and Garfield, but success in other fields made them leading Republicans after 1865. When Grant became president, Garfield was a supporter. Yet, by 1876 Garfield was among those disillusioned with Grant. Scandal had undermined Grant’s credibility, the peace policy in the west was in tatters, and Little Big Horn was on everyone’s lips. The Republicans in the former Confederacy were being eclipsed by the Democrats and left to their fate. When Garfield heard of Grant’s calm reaction to the scandal-driven resignation of Secretary of War William Belknap, he wrote, “I am in doubt whether to call it greatness or stupidity.”

Rutherford B. Hayes, himself an accomplished general, became president on a platform that repudiated “Grantism.” The Republicans soon fought each other as hard as they once fought the Democrats, dividing into two factions: Stalwarts and Half-Breeds. In the conventional interpretation, Stalwarts were more corrupt, machine oriented, and friendly to corporations. They were also more committed to equal rights and never let a soul forget that the Civil war was a righteous crusade. Half-Breeds favored reform, were more allergic to corporations, and if not exactly friendly to Southern Democrats, they found “waving the bloody shirt” tiresome.

The factions were more complex. Mark Summers, the preeminent scholar on the Gilded Age, has labeled the contest one really between “administration Republicans and Stalwarts,” making it less about policy and more about personality. Stalwarts decried Hayes making deals with Democrats such as David M. Key, or letting radicals like Carl Schurz near power. By 1880 they saw a need for a strongman to save the party. Roscoe Conkling, the powerhouse senator from New York, wanted his friend Grant back, who was then returning from a grand world tour. It was felt a strong hand was needed lest the nation split again. Indeed, the country had already been on the verge of mass violence over the controversial 1876 presidential election.

Conkling inspired strong feelings. He was a notorious womanizer and the kind of man known for charm and flattery but also a sharp and cruel tongue. He was a boxer who never backed down from a fight. He hated Hayes for removing his friend Chester A. Arthur as Collector of the Port of New York, the nation’s most prestigious and lucrative spoil. Arthur, large, fashionable, and amiable, was Conkling’s friend. They were a great duo, and Arthur’s genial manners and fine dinners smoothed Conkling’s rougher edges.

Conkling, Arthur, John Logan, and others decided a third term of Grant was needed to right the wrongs of Hayes. Chief among them was protecting the spoils system, in part because it was all that kept the Republican Party alive in parts of the South. As such, while the Stalwart’s boasted major party leaders, they relied on men from states where Republicans had a harder road to hoe. The Stalwarts though would have to sell Grant. True, he was the hero of Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, and Appomattox, but he was tainted by scandal and considered by some the butcher of Cold Harbor and blamed for the near disaster at Shiloh. Most of all, if two terms were good enough for giants such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Andrew Jackson, then who was Grant to tower above the men who defeated the British and forged a nation?

A smarter choice might have been Maine’s James G. Blaine. Called the “magnetic man,” he was courtly, smart, and had a talent for winning friends. His fans in the party were called “Blainiacs.” Like the Stalwarts, he favored political machines, waved the bloody shirt, and was not allergic to corruption. The trouble was, he and Conkling hated each other with a red-hot passion. Blaine described Conkling as having a “haughty disdain, his grandiloquent swell, his majestic, supereminent, overpowering, turkey-gobbler strut.” Blaine allied himself with Hayes despite the two having major disagreements over policy. Blaine was also not as committed to racial justice as the average Stalwart. George C. Gorham called Blaine’s political philosophy “Sham Republicanism, for years the concubine of the Democratic Turk.”

Hayes’s allies were in a tough spot. Blaine was not wholly trusted by them, but he was better than Conkling. As for Hayes, his declining influence and eagerness to get out of the White House made him a liability. In the end, the Half-Breed standard-bearer was Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman, brother of William Tecumseh. Dubbed the “Ohio icicle” Sherman was competent and loyal, first winning some notoriety for his early support of Abraham Lincoln. He would remain a fixture of Republican politics years after Conkling, Grant, Arthur, Blaine, and the rest had died or retired.

Grant had some trepidation about running again. Adam Badeau, his friend and biographer, noted that Grant “manifested as much anxiety as I ever saw him display on his own account.” By contrast John Russell Young, a New York Herald reporter Grant cultivated, thought Grant “does not evidence the slightest anxiety…He is as calm as a summer morning.” Young, on behalf of certain unnamed “friends” in New York and Washington, asked Grant to pull out. Julia, Grant’s beloved wife, moved from confidence to despair, noting “I did not feel that General Grant would be nominated. I knew of the disaffection of more than one of his trusted friends. The General would not believe me, but I saw it plainly.” Marshall Jewell, Governor of Connecticut and Postmaster General in Grant’s own Cabinet, publicly refused to support Grant. Conkling, fearing others would bolt, made it plain it was Grant or nothing.

The Chicago Tribune mocked Conkling as a “Warwick of the land –the King-maker whose power behind the throne will be greater than that of the occupant.” Grant wrote Don Cameron of Pennsylvania that his name might be withdrawn. Badeau thought it was “calculated, of course, to dampen the enthusiasm and bewilder the counsels of Grant’s most devoted adherents” and was “unlike General Grant’s ordinary character.” Young delivered it, but according to Senator George Boutwell of Massachusetts, the letter did not so much withdraw Grant’s name as leave it up to the men in Chicago. These men wanted Grant. Logan served Grant faithfully in the war and was itching for a showdown with the Half-Breeds. In 1876 Grant tried to get Conkling the nomination and Conkling wanted to return the favor in 1880. He intended with Grant’s nomination to get his revenge on Hayes and Blaine.

The 1880 Republican convention was deadlocked, a fight lasting some two weeks. Grant’s supporters held firm, all 306 delegates, confidant that some would bolt from Blaine, Sherman, or the lesser candidates. Eventually, a trickle of votes went to James Garfield, who was managing the convention on behalf of Sherman. For decades after, it was alleged that Garfield betrayed Sherman, as he had betrayed William S. Rosecrans after Chickamauga. If so, Garfield at least had the ability to make it look like he did not want the office. Blaine sent votes his way and Sherman pulled out. When it was over, Garfield, the darkest of dark horses, was the Republican Party’s standard-bearer.

When Conkling said in a low voice, “I congratulate the Republican Party of the United States upon the good nature and the well-tempered rivalry which has distinguished this animated contest” and moved that Garfield’s nomination be unanimous. There were calls for him to speak up. He refused and cut short his words. Cameron was next asked to speak, but when his name was called, he pretended to be lost on the floor. In Puck, a Joseph Keppler cartoon called “The Appomattox of the Third Termers” showed a humbled Grant handing his sword to an erect and proud Garfield. Behind Garfield were men in a position dubbed “Fort Alliance” garrisoned by reformers, while Grant’s men were prostrate on the ground. The cartoon sharply turned upside down the imagery of around Appomattox, Grant’s finest hour.

After the nomination fight, Conkling and his crew treated their stand as a badge of honor. They formed the “Three Hundred and Six Guard,” complete with annual dinners and a commemorative gold coin, emblazoned with “The Old Guard.” Given the events of 1881, their actions came to be seen as a kind of political version of the Ariobarzanes’s stand at the Persian Gate, a brave fight on the eve of their destruction.

Garfield has a beautiful memorial on a dominating hilltop in Lakeside Cemetery. It can be seen from the tall buildings in downtown Cleveland.

In 1880 Don Cameron controlled the Pennsylvania delegation to the Republican convention. When his efforts to nominate former President Grant for a third term failed, he threw the Pennsylvania delegation behind James Garfield

Did Julia want Grant to be nominated? I would think she’d be sick of the Presidency!