Devilish Dwight’s Drunken Disasters

ECW welcomes back guest author Brian D. Kowell

He was a tyrannical misfit, a drunk, “a notorious rake, and a lusty, lecherous womanizer whose debaucherous tastes ran from high-priced New Orleans whores to dusky and unwashed maidens who followed the army” regardless of the color of their skin. Some thought he was a “drunken mad-man.” He was Union General William Dwight.[1]

Born on July 14, 1831 in Springfield, Massachusetts, Dwight was the second of seven sons of William Dwight, one of the richest and most influential men in Boston, and Elizabeth Amelia Dwight. As a boy, young William was outspoken, boisterous, rude, and troublesome.[2]

In 1849 Dwight was appointed to West Point, but failed to graduate. He resigned on January 31, 1853 due to his heavy drinking and a preference for brothels over barracks. He returned to Boston to work in manufacturing cotton goods, married Anna Robeson on January 1, 1856, and moved to Philadelphia soon after.[3]

As the Civil War began, he was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the 70th New York Volunteer Infantry, second in command to Col. Daniel Sickles. When Sickles was promoted commander of the Excelsior Brigade, Dwight assumed command of the 70th New York’s 750 men. At Williamsburg on May 5, 1862, the Excelsior Brigade engaged Virginia troops under A. P. Hill. They fought southwest of Fort Magruder in a tangled, wooded ravine in a “pitiless rain.” Dwight’s regiment was the last to go into action. Urging his men on, Dwight received a wound in the leg and went down. Two more wounds followed before he lost consciousness. The 70th New York suffered 380 casualties for a 50-percent loss of strength before pulling back. Dwight was left on the field presumed dead. His wounds, however, were not fatal, and he was taken prisoner. He was later exchanged on November 15, 1862, promoted to brigadier general, and sent west.[4]

Dwight was given the 3rd Brigade in Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Sherman’s 2nd Division of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ XIX Corps, Army of the Gulf. Marching toward Port Hudson, Louisiana, Dwight drank heavily. Through an alcoholic haze, he spied a young soldier, Henry Hamill, plundering for food. The drunken Dwight ordered the soldier shot for his offense, even though thousands of other soldiers (including Dwight’s own staff) had been similarly engaged. This had a bad effect upon his brigade’s soldiers, especially since Dwight was seen riding in a rich carriage drawn by fine horses and was known to have a cache of excellent liquors that he appropriated from planters’ homes nearby.[5]

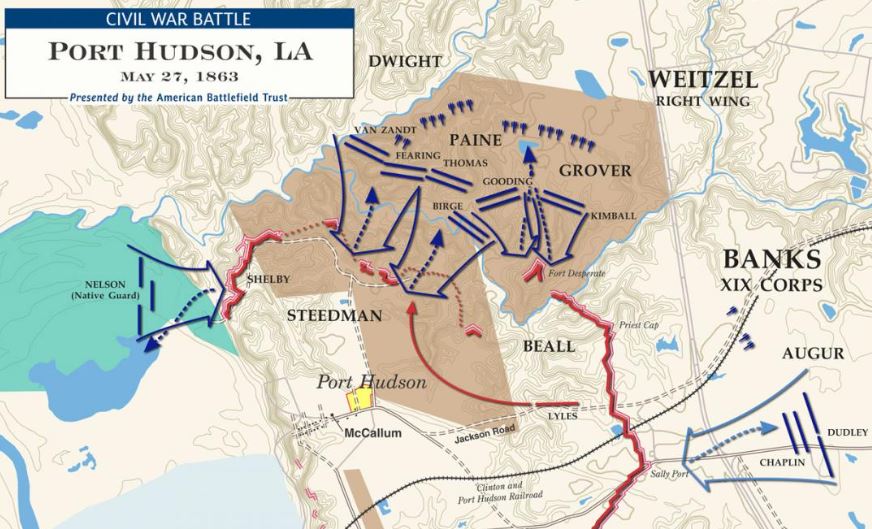

Banks’s army besieged Confederate forces under Maj. Gen. Franklin Gardner defending strategically important Port Hudson on the Mississippi River. Dwight’s brigade held the far left flank of the Federal line next to the river.

On May 27, 1863, Banks ordered a grand assault. The 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards – two all-Black regiments – were in Dwight’s brigade. Dwight ordered their commander, Col. John Nelson of the 3rd Native Guards, to assault the Confederate entrenchments, while Dwight monitored from the rear, probably within reach of a bottle of whiskey. Unfamiliar with the topography over which his Black troops would have to traverse, Nelson asked Dwight what to expect. The answer was that the ground was smooth. This was a lie, as neither Dwight nor his staff had examined the ground. Dwight reassured Nelson that, if needed, White regiments would support him.[6]

That morning Dwight must have been in a sharing mood, as he had the Black soldiers issued a whiskey ration that exceeded the standard ration issued to troops before an assault. The Native Guards stepped off around 10 a.m. into terrain anything but smooth and into a maelstrom of fire, without their leader. Nelson, too, had decided to stay behind. The assault force took terrible casualties, losing 50% of their strength which littered the field. Nelson, recognizing their hopeless situation, sent aides to Dwight for permission to withdraw.[7]

Dwight was furious. His inebriated mind was unable to comprehend the futility of the charge. He accused the men of cowardice and their officers of incompetence and “fairly shook with rage. His unattractive red face was covered with sweat and his breath reeking of alcohol.”[8] “Tell Colonel Nelson I shall consider he has done nothing unless he carries the enemy’s works,” Dwight shouted. “Tell Colonel Nelson to keep charging as long as there is a corporal’s guard left. When there is only one man left, let him come to me and report. Charge! Charge again!”[9]

Luckily for his men, Nelson refused the senseless order of a drunk and had his men pull back, continuing to fire so that Dwight might be fooled that the attack was still in progress.[10]

Dwight wasn’t the only Union officer drinking that day. While Dwight’s attack floundered, the rest of the division was ordered to assault the Confederate works across Slaughter’s Field. Unlike Dwight, Gen. Thomas W. Sherman examined the ground and decided against attacking. The problem was he never informed Banks, who went to Sherman’s headquarters to find out why the attack had not been made. When Banks arrived, he exploded when he found Sherman with a glass of wine in his hand (not his first) and bottles of wine on a linen-covered table as Black servants stood nearby with white napkins over their arms. Words flew between the two, Sherman arguing that the field was sheer suicide to charge across, and Banks telling him to pack his bags, because he was replacing him.[11]

When Banks rode off, Sherman, instead of packing his bags, ordered his troops to form for the charge. Quite drunk, Sherman was astride his horse getting ready to personally lead the charge when one of Banks’ staff officers found him and told him he was relieved. Sherman dashed his hat to the ground and refused. With bugles sounding the charge, Sherman raised his sword, and his two brigades under Frank S. Nickerson and Neal Dow stepped out with Sherman mounted in front.[12]

It wasn’t long before Sherman’s horse went down with the general pinned beneath the beast. Helped from beneath the dead animal, the dazed division commander ignored entreaties to go to the rear and started forward on foot. After taking a dozen steps his right leg was shattered by grapeshot.[13] With Sherman’s wounding, Dwight assumed division command.

The siege of Port Hudson continued, with Dwight now responsible for a greater number of troops. Little did his new command know what was in store for them. The next installment will explore Devilish Dwight in division command.

Brian Kowell is a past president of the Cleveland Civil War Round Table and has had an article published in America’s Civil War July 1992 edition about the Buckland Races.

Endnotes:

[1] David C. Edmonds, The Guns of Port Hudson: The Investment, Siege, and Reduction, (Lafayette, LA: Acadiana Press. 1984), Vol. 2, 245.

[2] Benjamin Woodbridge Dwight, The History of the Descendants of John Dwight of Dedham, Massachusetts, (J. F. Trow & Sons Printers and Bookbinders, 1874), Vol. 2, 3-5.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders, (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 1964), 134-135; John H. Eicher and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands, (Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 2001), 220, 721; Earl C. Hastings, Jr. and David S. Hastings, A Pitiless Rain: The Battle of Williamsburg, 1862, (Shippensburg, PA: White Maine, 1997), 78, 83-84.

[5] Edmonds, The Guns of Port Hudson, 387; Edward Bacon, Among the Cotton Thieves, (Detroit: The Free Press Steam Book and Job Printing House, 1867) 158-159.

[6] Edmonds, The Guns of Port Hudson, 52.

[7] Lawrence Lee Hewitt, Port Hudson: Confederate Bastion on the Mississippi, (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 1987), 147-150.

[8] Edmonds, The Guns of Port Hudson, 57.

[9] Bacon, Among the Cotton Thieves, 161. Edwards, The Guns of Port Hudson, 57-58.

[10] Edmonds, The Guns of Port Hudson, 58.

[11] Ibid, 62.

[12] Ibid, 63

[13] Edmonds, David C., The Guns of Port Hudson: The Investment, Siege, and Reduction, (Lafayette, LA: Acadiana Press. 1984), Vol. 2, 71.

Great story, was intrigued by the connection to the Excelsior Brigade

No wonder the South wanted to leave the Union…

How did he ever avoid the fate that befell AP Hill at West Point?

There is a lot of speculation on the order of: what if Jackson had survived and been at Gettysburg, or what is A.S. Johnson had survived Shiloh. A better “what if” would have been, what is this jasper hadn’t survived his first wounding?

Compare this general to Joshua Chamberlain’s actions and words as he addressed his men, prior to a perilous attack against entrenched troops at Petersburg, cited in ECW Blog entry by Sarah Kay Bierle dated 6/18/19.

“He walked along the lines of his soldiers, most lying prone on the ground. Later, observers remembered the former professor turned soldier saying:

“Comrades, we have now before us a great duty for our country to perform, and who knows but the way in which we acquit ourselves in this perilous undertaking may depend the ultimate success of the preservation of our grand republic. We know that some must fall, it may be any of you or I; but I feel that you will all go in manfully and make such a record as will make all our loyal American people grateful. I can but feel that our action in this crisis is momentous, and who can know but in the providence of God our action today may be the one thing needful to break and destroy this unholy rebellion.”