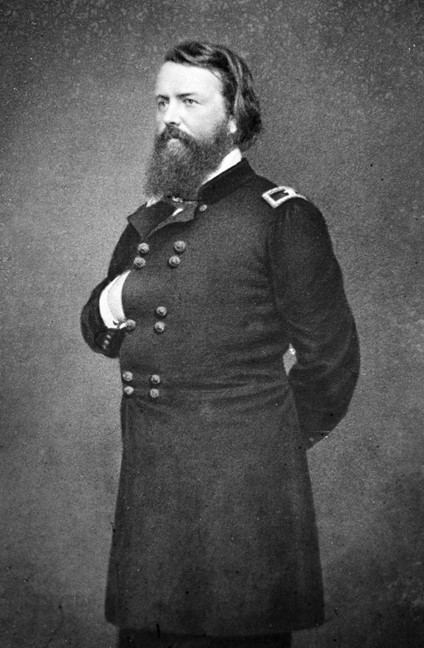

Ulysses Grant in Northern Missouri, July 1861

ECW welcomes guest author Greg Wolk.

DATELINE: MONROE STATION, MISSOURI, JULY 10, 1861. A thousand men or more surround an Illinois regiment in this railroad town 20 miles west of Hannibal. The aggressors are secessionists, organized loosely into a force called the Missouri State Guard. The defenders: 600 soldiers of the 16th Illinois Infantry Regiment under Col. Robert F. Smith, a man who just learned a valuable lesson.

His men arrived in open rail cars on July 8, after leaving their base at Quincy, Illinois. Smith had six companies of his own regiment, plus home guards from Quincy. From Monroe Station, he set off on foot in search of the Missouri State Guard, but 10 miles south of the station he ran into light resistance.

Smith promptly turned his column around, to return to his base of supplies. He had failed to leave a sufficient force in Monroe Station to protect the train cars and supplies; what greeted him in the town was a scene of utter devastation. The State Guard force that he confronted south of town was approaching. Smith brought his men into the most substantial masonry structure in town, a female academy, which is where the State Guard surrounded him. As the crack of small arms fire filled the air, the rebels lobbed shells from a 9-pounder into Smith’s position. The contest in town had stalemated, however, by the time Union help arrived.

During the time of Col. Smith’s adventure, another new Illinois Colonel – one by the name of Ulysses Grant – was marching a green regiment west from Springfield, Illinois. Grant halted his 21st Illinois at Naples, Illinois where he awaited river transportation to southeast Missouri. Smith’s folly at Monroe Station, and destruction of a vital bridge on the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad nine miles west of there, sent shock waves throughout the area. Loss of the bridge severed Quincy’s rail link to the west. Grant was urgently re-directed to north Missouri, where he and his regiment arrived on July 11, 1861. His first assignment in the war zone was guarding the site of the destroyed bridge while engineers re-built it.

The Hannibal & St. Joseph was not the only railroad in upper Missouri that came under attack that month. The North Missouri Railroad, which connected St. Louis to the Hannibal & St. Joseph at a junction point in Macon, Missouri, passed through hostile country for much of its 160-mile length. Brigadier General John Pope, who took command of Union troops in this area in mid-July, found the local civilian population particularly vexing. Small bands of “secesh” citizens, less organized than those who visited Monroe Station, were causing serious damage by acts of sabotage. For the most part, these acts were directed at the infrastructure of the North Missouri Railroad. Within a week after he arrived on the scene, Pope issued a draconian order intended to combat this vandalism. To this day, civil libertarians decry Pope’s order, which levied fines on the citizenry to pay for repairs to the railroad, without so much as a nod to due process.

The Missouri State Guard brigadier who precipitated the fight at Monroe Station was Mexican War veteran Thomas A. Harris. He caused fits within the Union high command. On July 14, Grant took his regiment on a two-day “chase” of Harris to Florida, Missouri, with no success. The chase of Harris did, however, produce a memorable passage in Grant’s Memoirs: Crossing over a hill near Florida only to find his adversary gone, Grant learned that Harris had been as much afraid of him as he had been of Harris. “This was a view of the question I had never taken before; but it was one I never forgot afterwards.”[1]

Just after the regiment returned from Florida, Grant was ordered to Mexico, Missouri. An important center of commerce on the North Missouri Railroad, Mexico had been targeted for some of the mischief that riled Pope. When Grant received these orders, he was already under orders to report to Pope, but in Alton, Illinois. Instead, Pope joined Grant in the field.

Once Pope formally took charge, and even before he arrived in Mexico with his regiments, he began to deploy troops under his command. He summoned Grant’s 21st Illinois from the north, as has been noted. He also sent to Mexico two companies of the 8th Missouri Volunteer Infantry, recently enrolled in St. Louis, and four companies of the 2nd Missouri Infantry (three months) under command of Lt. Col. Friedrich Schaefer. General Pope was acting quickly and effectively to take control of Union interests in northeast Missouri, but events in and around Mexico were outpacing him.

On July 15, the two companies of the 8th Missouri, and Schaefer’s four companies, left St. Charles for Mexico via the North Missouri Railroad. After passing Wentzville (20 miles west of St. Charles), the train was fired on by parties hidden in the woods along the tracks. Sustained fire from the woods caused the company officers to send out skirmishers; then they decided to back the train into Wentzville for the night. The next morning, July 16, the journey resumed, but with the same result. In the daylight, the men made slightly better progress. For part of the route, commanders put six riflemen out front in a hand car, as well as skirmishers who “walked” the train through the gauntlet.

Close to the place where the men confronted the secessionist party the day before, the train again came under fire. Immediately, five of the six men in the hand car fell wounded. The wounds sustained by Private Bill Pease proved mortal. He died the night of July 16 in Montgomery City, about 40 miles northwest of the skirmish site.[2]

The mid-July carnage on the North Missouri Railroad did not end when the 8th Missouri reached Mexico. On July 18, a drama unfolded near another station on the road, a place called Martinsburg in Audrain County (about equidistant from Montgomery City and Mexico). In this neighborhood, a detachment of Union horsemen from the 1st Missouri Cavalry (Shluttner’s) was operating independently of the infantry. An officer, 2nd Lt. Anton Jaeger, became ill as he traveled to reach Shluttner’s command. Another man on the Mexico-bound train was a staunch Unionist from nearby Danville named Benjamin H. Sharp. The two men left the train at Wellsville, Jaeger because he was ill and Sharp because he wanted to care for the lieutenant’s welfare. Sharp borrowed a buggy from a man he knew in Wellsville, and they set out for Mexico. Sharp was not familiar with the road network north and west of Wellsville.

Enter Alvin S. Cobb, secessionist from Cobbtown, Montgomery County. He was roaming northwest Montgomery County, where it borders Audrain County, when he and his band of followers came in contact with Sharp and Jaeger west of Martinsburg. Cobb was described by a contemporary as “a large man of magnificent physique,” who carried about him a “suspicion of something sinister.”[3] Cobb’s generally frightful appearance was enhanced by an iron hook that poked out of his sleeve, where his left hand had been.

Sharp had taken the wrong road, and he drove into Cobb’s band of guerillas. They fired into Sharp’s buggy, seriously wounding both Sharp and Jaeger. The wounded men were taken into Martinsburg, then to a field north of the town and summarily executed.[4] The case of Lt. Jaeger was particularly jarring and heart-rending. He was the St. Louis brewer who owned “Jaeger’s Beer Garden,” a fixture of south St. Louis’s German community. The details of his fate were not confirmed until July 28, when his body, with Sharp’s, was found in a shallow grave. In St. Louis, Jaeger’s wife Eva waited for the news with their three children, the youngest of which (a son) was not yet one month old.[5]

About mid-day on July 20, 1861, Grant brought his 21st Illinois infantry into Mexico. What confronted him was the first issue of a camp newspaper called Star Spangled Banner, reported and printed by the men of the 8th Missouri. The paper, dated July 19, reported the fighting west of Wentzville and the deadly incident in Martinsburg. On July 21, two days after the Martinsburg killings, soldiers of the 8th Missouri took two Danville men from their homes, then shot them on a prairie south of Montgomery City.[6] A third man was killed nearby. On the same day, the armies in the East fought at Bull Run, and Pope issued his ill-conceived order to charge citizens for damage done to the railroad. North Missouri was in full panic.

While there is no record that Ulysses Grant knew at the time of the retaliatory killings in Danville, when he penned his Memoirs this master of understatement would say: “My arrival in Mexico had been preceded by that of two or three regiments in which proper discipline had not been maintained.”[7]

Mr. Wolk is a retired trial lawyer and writer. He serves on the Boards of Directors of the Jefferson Barracks Heritage Foundation and the National U. S. Grant Trail Association, both based in St. Louis. His works include Friend and Foe Alike: A Tour Guide to Missouri’s Civil War (Eureka, MO: Monograph Publishing Co., 2010), and numerous magazine articles focused on the Civil War in Missouri. His great-great-grandfather was a private in the 21st Illinois Infantry, marching with Grant from Springfield, Illinois, to Monroe Station other places mentioned in this article.

Endnotes:

[1] Ulysses S. Grant The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1990, 164.

[2] The Star Spangled Banner, Vol. 1, No. 1, July 19, 1861, published at Mexico, Missouri by the 8th Regiment, Missouri Volunteers, Chester Childs, editor.

[3] Joseph A. Mudd, With Porter in North Missouri. Washington: The National Publishing Company, 1909, 204.

[4] Letter of William Martin of Martinsburg, Missouri dated July 29, 1861, Henry Almstedt Papers, Missouri History Museum Archives, St. Louis (A0022).

[5] Application, 1862, Eva Jaeger, widow’s pension application no. 352070; service of Anton Jaeger (1st Lt. 1st Missouri Cavalry, Civil War), National Archives, Washington, DC.

[6] History of St. Charles, Montgomery and Warren Counties, Missouri. St. Louis: National Historical Company, 1885, 618-620.

[7] Grant, 165.

Greg Wolk

Congratulations on an informative, concise exposé of Guerilla War Missouri and U.S. Grant’s apparent brief exposure to that situation [July to September 1861.] Many forget that Grant had lived in Missouri, and visited St. Louis frequently prior to the Secession Crisis, and he would have been aware of the conflicting political beliefs held by neighbors and within families in that State. For Colonel Grant, operations in Missouri provided an opportunity to assert himself, dominate peers, achieve promotion… and then leave, for command in Cairo, and subsequent successes in Kentucky and Tennessee.

All the best

Mike Maxwell

thanks for telling this comparatively little known tale of Grant’s early career … his characteristic confidence, aggressiveness, and bias for action was on full display early in his career.

Hi my name is Kaleb Jaegers. Anton Jaegers is my great great great grandpa, this article has shown more information about my grandpa. I have a photo of him if you’d like to include it in your article. My email is kaleb.jaegers@icloud.com!

I have collected a great deal of information about Colonel Robert F. Smith’s 16th Illinois Infantry Regiment’s service during the Civil War; I have several ancestors who served in it. Two were in the relief Battalion that were sent from Palmyra Missouri to rescue Colonel Smith’s command from the Missouri State Guard under Brigadier General Thomas Harris. The “Affair” at Monroe Station was quite farcical; The 21st Illinois, under Colonel Grant, was his first military foray of the conflict and he touches on it briefly in his Autobiography as you have mentioned. The “skirmish” was over by the time the 21st Illinois arrived. Speaking of his Autobiography, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) was instrumental in the publishing of this, his last work, which provided financial security for his family after his death. I have read very little about Samuel Clemens’ participation in the Civil War. It might surprise some, but “Mark Twain” claimed he was a Lieutenant under General Harris and in the limited time between the commencement of hostilities and his removal to the Nevada Territory he was in the “neighborhood” so to speak. Possibly present, possibly participating in the “Affair” at Monroe Station.

DAVID L GORDON

You are invited to check out Mark Twain’s “A Private History of a Campaign That Failed.” He states, “An hour later we met General Harris on the road… Harris ordered us back, but we told him there was a Union Colonel coming…. there was going to be a disturbance, so we had concluded to go home…………” Twain–at that time still Clemens– claims that the Union colonel was–of course–U. S. Grant.

I am a great great grandson of Anton Jaeger doung research on this very topic in St Louis this week. Your account adds interesting detail and confirms the story of the ‘0ne-handed rebel.’ Lt. Jaeger had previously offered his beer garden in St Louis for the use union volunteers. An account of Colonel Grant’s march to Camp Jackson from Jaeger’s beer Garden is posted at the Civil War Museum at Jefferson Barracks.

Greetings: The Missouri Historical Society possesses a great deal of information on the events and personalities in Northeast Missouri during the rebellion.

Jim: This is Greg Wolk. I hadn’t checked my ECW for a few weeks. I have a new book out called John Fremont’s 100 Days: Clashes and Convictions in Civil War Missouri. Half of a chapter is devoted to Martinsburg and Ulysses Grant’s involvement. But in any case, my condolences for your family. What an awful event.

Jim, I’m sorry i hadn’t checked in on ECW for some weeks. I have a book out that was released in October called: John Fremont’s 100 Days: Clashes and Convictions in Civil War Missouri, that devotes 1/2 a chapter to the Martinsburg killings and the sad and shocking fate visited upon your ancestor. I’d love to share some of my research with you.

Greg Wolk