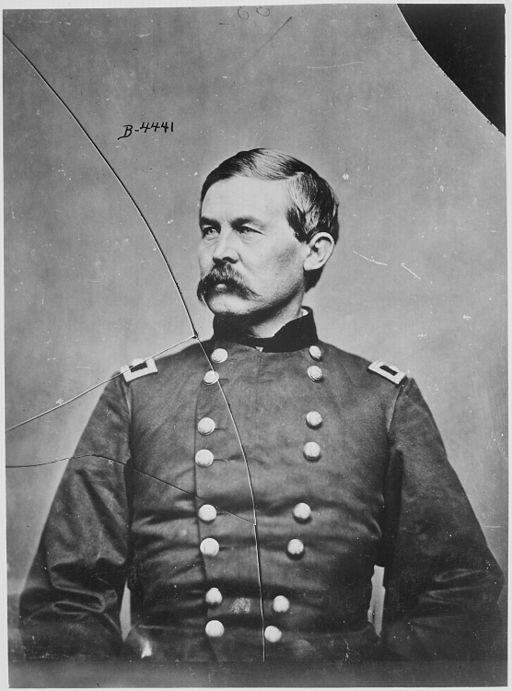

John Buford, Billy Burke, and the Decision that United Them Across Nearly 140 Years

On the evening of June 30, 1863, 37-year-old Brig. Gen. John Buford did not know when help was coming. His two brigades of cavalry, about 2,700 men, had entered the crossroads town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, that morning and “Found everybody in a terrible state of excitement.” How many of the enemy were in front of him Buford did not know, but he wrote back to army headquarters “I have many rumors and reports of the enemy advancing upon me from toward York.” There were reports of at least two Confederate corps in the immediate area—and Buford had no idea when the Federal infantry would arrive. Until they showed up, Buford and his cavalrymen were on their own.[1]

One of Buford’s subordinates brushed off the threats and boasted they could repel whatever came at them. “No you won’t,” Buford snapped. “They will attack you in the morning and they will come ‘booming’ – skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own until supports arrive.” Another of Buford’s staffers noted, “He seemed anxious, more so than I ever saw him.”[2]

Buford could do nothing but wait for the morning and hope for the infantry. But no matter what came, no matter the consequences, Buford decided to stay right where he was.

***

William “Billy” Burke, Jr., joined the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) in 1982. He followed his father, a deputy chief, into the department, and soon proved his own merit. Burke received a promotion to lieutenant in 1991 and taught probationary firefighters at the department’s legendary training facility, “the Rock,” on Randall’s Island. Burke then received a promotion to captain of Engine 21 in June 2001. When he wasn’t firefighting, Burke worked as a lifeguard on Long Island.[3]

Outside his career as a firefighter, Burke was a massive history buff, and especially liked studying the Civil War. Burke loved talking about the war and its battles “to anyone who would listen.”[4] On more than one occasion, he took first dates out to Ulysses S. Grant’s tomb in Manhattan. But his own personal hero, he told friends, was cavalryman John Buford. An ordinary man doing extraordinary things, Burke figured, was a good legacy, and one which a firefighter could look up to.

In 2001, Burke was 46 years old, and on the morning of Sept. 11, he was at work in Engine 21’s quarters on East 40th Street. As captain, Burke commanded five other firefighters.

At 8:46 a.m., out of the clear blue sky the hijacked American Airlines Flight 11 slammed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

Five seconds later came the FDNY’s first official response. A battalion chief keyed his radio and calmly, unbelievably calmly, said to the dispatcher, “We just had a plane crash into upper floors of the World Trade Center. Transmit a second alarm and start relocating companies into the area.”[5]

Within minutes, firefighters threw on their bunker gear, jumped into their trucks, and with sirens screaming, made their way towards the burning tower. As the true seriousness of the calamity became clear, the department called for a third, fourth, and fifth alarm.

Captain Burke knew, even before its official dispatch, that Engine 21 would be responding. “He let us know to start getting the [air] bottles ready,” one firefighter remembered.[6] At 9:00 a.m., Engine 21 got the tones to respond to the World Trade Center. As Engine 21 left its quarters, United Airlines Flight 175 hit the second tower. It was becoming rapidly apparent that these were not accidents.[7]

Six and a half miles separated Engine 21’s quarters and the World Trade Center. It took 17 minutes to cover the distance; with traffic so heavy in places some firefighters were forced to walk to the Towers, Engine 21’s arrival was lightning fast. The engine’s chauffeur turned left onto Vesey Street and parked near a hydrant. Captain Burke and his company hopped out, gathered their equipment, and headed inside the North Tower.[8]

***

John Buford climbed into the cupola of the seminary, field glasses in hand, and stared towards the oncoming enemy.

His troopers were fighting doggedly, slowing the Confederate advance. The carbines cracked and Buford’s one battery of artillery thudded in support— he split the six guns into sections and spread them out, hoping to conceal how thin his line really was.

Buford hid his fears from the staff around him. More Confederates were beginning to push down the Chambersburg Pike, and he wasn’t sure how long he could hold on. But Buford recognized the importance of the roads coming into town, and knew he had to resist the enemy as long as he could. Later, as Buford spoke to one of his brigade commanders, he said sternly: “We must hold this if it costs every man in your command.”[9]

***

Inside the lobby of the North Tower, fire companies waited for their orders. Some had already begun ascending, one flight of stairs at a time, towards the fire spanning the 93rd—99th floors.

A French documentarian, who had spent the summer embedded with the FDNY, happened to catch Capt. Burke as he stood in the lobby. It was only a passing shot, maybe four seconds. Burke took his helmet off, adjusted a strap over his shoulder, and put the helmet back, ready to go to work.

Soon after arriving, Engine 21’s crew pried open an elevator, rescuing a woman “scared to death.”[10] Another elevator was in working order, at least up to the 24th floor. Almost 45 minutes had passed since the North Tower had been struck, and now with the South Tower burning, the fire department’s resources were stretched even further. Calls still came from people trapped above the impact zone. Daniel Nigro, the FDNY’s Chief of Operations, later described the department’s ethos: “All the dispatcher could say is, ‘We’re coming for you.’ So, we like to keep our promises. You know, we told them we’re coming. We’re coming.”[11]

Captain Burke relayed to his crew what the department’s top brass had decided: “We’re not trying to put the fire out now. We’re going to try to save people.” Burke and his firefighters got into the working elevator, rode it to the 24th floor, and then started climbing on foot, one step at a time.[12]

***

A flurry of hooves announced the arrival of Maj Gen. John Reynolds, commanding the left wing of the Army of the Potomac. Behind him, the First Corps’s infantry was nearing the scene of fighting.

“What’s the matter, John?” Reynolds called out to Buford.

“The devil’s to pay,” the Kentuckian-born Buford answered, and when Reynolds asked if he could hold a little longer, answered laconically, “I reckon I can.”

It would take more time for Reynolds’s men to deploy, but Buford had done his job. His exhausted and powder-grimed men had held long enough.[13]

***

Burke and his men had made it to the 27th floor. The entire building began to shake, and the firefighters leapt to the floor.

Once the building settled, Burke looked out the window. He turned to another captain and said, “The other building just collapsed.”[14]

Crews inside knew that if the South Tower could collapse, the North Tower, which had been burning even longer, was in imminent danger. Orders to evacuate began to chirp on their radios.

And then Burke came across Ed Beyea, a quadriplegic who worked on the 27th floor of the North Tower. Confined to his wheelchair and joined by a close friend, Abe Zelmanowitz, the two men were stuck with no way down the winding stairs of the North Tower. Burke refused to leave them behind. He ordered the rest of the company to continue their descent and instructed them to all meet back up at the engine outside. Even as others radioed Burke, telling him to get out, he continued to tell them to keep going and meet at the engine. The other members of Engine 21 made it to the lobby and escaped safely. Burke steadfastly remained by Beyea and Zelmanowitz. In that moment, 138 years after his hero made the same decision, Billy Burke decided to stay, no matter what came, no matter the consequences, right where he was.[15]

The North Tower collapsed at 10:28 a.m. As the heavy dust clouds settled over New York, thousands of others rushed in to try and find survivors among the debris. Though they dug with frantic energy, only 20 survivors were pulled from the debris. None of them came from the 27th floor. In August 2002, DNA matches for both Beyea and Zelmanowitz were discovered. No remains were ever found of Capt. William Burke.

On October 25, 2001, the FDNY memorialized him. Hundreds poured into St. Patrick’s Cathedral. “To know Billy was to make you want to be a better person,” one remembered. Another said, “People don’t die if they are remembered, so keep telling those Billy Burke stories.”[16]

Recognizing Billy’s love of the past, his brother Michael said, “He belongs to history now.”[17]

***

John Buford survived Gettysburg, but died by the end of the year, a victim of typhoid fever. He was honorably buried at West Point’s cemetery.

Like his personal hero, Capt. Billy Burke knew there was a job to do. It would not be easy— but someone had to do it. As Buford stood his ground and bought time for the rest of the army, Burke charged up the tower to try and rescue others. His insistence that the rest of Engine 21 leave the tower led to their safe evacuation— Burke was the only fatality from the company.

Engine 21, with its cab burned out from the collapse, was pulled from the wreckage, and now sits on display within the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

John Buford and Billy Burke were two regular people thrust into extraordinary circumstances. By their actions, they became immortal.

__________________________________________________________________

[1] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 27, pt. 1, 923-24.

[2] Aaron B. Jerome, “Buford in the Battle of Oak Ridge,” in The Decisive Conflicts of the late Civil War, or Slaveholders’ Rebellion, Volume 3: The Pennsylvania-Maryland Campaign of June-July, 1863, ed. J. Watts De Peyster (New York: MacDonald & Co., 1867), 152.

[3] Jay Jonas, “Division 7 Training and Safety Newsletter: Captain William F. Burke, Jr.” (September 2018).

[4] Ibid.

[5] New York City Fire Department Manhattan Dispatcher Audio Tape Transcript, Sept. 11, 2001; The 9/11 Commission Report, (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Press, 2004), 289.

[6] World Trade Center Task Force Interview, Firefighter William Casey (Engine 21), December 17, 2001, 2.

[7] Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster: The Emergency Response Operations (Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2005) 201; World Trade Center Task Force Interview, Firefighter Sidney Parris (Engine 21), December 14, 2001, 2.

[8] Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster: The Emergency Response Operations (Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2005), 209. Engine 21 transmitted the code 10-84, FDNY shorthand for a unit that had arrived on scene.

[9] New York at Gettysburg, Vol. 3 (Albany: J.B. Lyon Company, 1900), 1,153.

[10] World Trade Center Task Force Interview, Firefighter John Snow (Engine 21), January 13, 2002, 3.

[11] 60 Minutes Remembers 9/11: The FDNY, September 12, 2021.

[13] William L. Heermance, “The Cavalry at Gettysburg,” Personal Recollections of the War of the Rebellion: Addresses Delivered Before the Commandery of the State of New York, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States Third Series (G.P. Putnam’s Sons: New York, 1907), 201.

[14] Dennis Smith, Report from Ground Zero (New York: Penguin Group, 2003 reprint), 95.

[15] Jim Dwyer and Kevin Flynn, 102 Minutes: The Untold Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2005), 42-43, 219-20.

[16] Smith, 329.

[17] Michael Burke, quoted in “Gettin’ Salty Podcast,” Episode 187, February 19, 2024.

My God! What a great post. Brought tears to my eyes. Two American heroes.

Stunning tribute. Thank you.

Brought tears to my eyes too. None of my immediate friends perished in that disaster. A workmate lost his sister. My wife’s workmate lost her policeman husband. A close friend lost his fire-fighter nephew. He then spent a lot of time at Ground Zero, dying of pancreatic cancer in 2015. By now the number of first responders who have died from cancer outnumbers those killed that day. My friend, neither a policeman or fireman, is not listed in that total.

Fantastic article tying the past with the (recent) present. Two American heroes that we should never forget.

Ryan, an amazing story you have provided us. Thank you very much for sharing this.

Great job. Regular people make the world go.

Brilliant.

Excellent. Thanks.

Ryan, Thanks for making this historical connection … a great example of two men living the core values of their organizations

NYFD — Bravery, Dedication, Service, Honor …

U.S. Army — Personal Courage, Selfless Service, Duty, Honor …

Ryan. Thank you very much for this story. My brother, Captain William F Burke Jr. would have loved this story! As you state Billy was a huge student of the civil war and particularly Gettysburg mainly because of the stories of ordinary men doing amazing things in the face of overwhelming adversity. Your story keeps Billy’s story going and the stories of so many men and women who risked their own lives to assist so many that fateful day. Thank you.