Writing Tempest: Capturing the Unrelenting Nature of the Overland Campaign

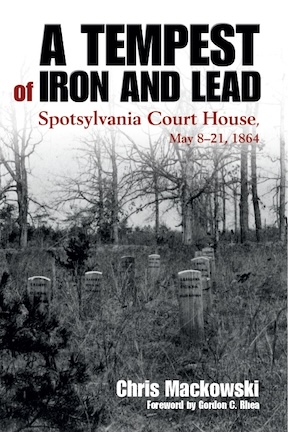

One of the challenges of the 1864 Overland Campaign was its unrelenting nature. One of the challenges of writing A Tempest of Iron and Lead: Spotsylvania Court House, May 8–21, 1864 was finding a way to reflect that in the text itself.

One of the challenges of the 1864 Overland Campaign was its unrelenting nature. One of the challenges of writing A Tempest of Iron and Lead: Spotsylvania Court House, May 8–21, 1864 was finding a way to reflect that in the text itself.

Federal forces left their winter camps around Brandy Stations and Culpeper on May 4, 1864, and Confederates immediately responded with movement of their own. Both armies spent the next six weeks marching, fighting, maneuvering, fighting, and marching some more. Their entwined dance took them from the banks of the Rapidan River to the banks of the James River.

Six weeks.

This was a far cry from the usual fight-and-disengage rhythm they had experienced prior in the war. Even the stretch of Cedar Mountain/Second Manassas/Antietam had periods of rest among the marching and fighting and longer periods between the battles.

When armies left the Wilderness on the night of May 7 they fought their way down the road to Spotsylvania, where they settled into new lines on the morning of May 8. The Wilderness and Spotsylvania were not necessarily the discreet events most people think of. The same could be said for the rest of the campaign, too.

“We stood sorely in need of both quiet and rest, having been continually on the march and fight since the night of the third of May,” wrote John Haley of the 17th Maine on May 14. “My endurance has been so outrageously taxed that I sometimes envy those who have laid down their lives; they sweetly sleep while we toil on.”

Imagine that: being so exhausted you envy the dead their ability to sleep on.

I really wanted my Spotsylvania book to somehow capture this. Initially, I considered a page layout that contained no chapter breaks at all, the way Cormac McCarthy’s The Road just keeps going on and on, with some section breaks to denote the passage of physical distance and time but otherwise an unbroken journey. The reader’s experience emulates the journey of the father and son.

I soon found that approach a bit too literal. I tend to write in short paragraphs because shorter paragraphs improve readability by making the page subconsciously easier on the eye. To basically turn the book into a single block of text, even with section breaks, worked against the readability I otherwise strive for. I didn’t want my artsy-fartsyness to get in the way.

For similar reasons, I considered—and then decided against—clustering all my images into a single photo insert. I initially thought that placing them in the chapters would disrupt that “relentless” feeling I was going for. Again, I decided in favor of readability over relentlessness, using the photos to help the pages breathe.

Another major argument in favor of this approach is that I really needed to have the maps right there with the actions they depict rather than in a map section. The book has two-dozen Edward Alexander-designed maps that all help make confusing action less confusing; separating those maps from the text would really undermine that idea.

I mulled several other layout/design options for the book. Chapter titles or subheaders all felt too neat and tidy, though. The battle of Spotsylvania Court House was not a series of discreet events for these armies but, rather, a blur of action on several simultaneous fronts. Days of rain made things run together even more.

I finally settled on a day-by-day approach. The manuscript is broken up by May 8, May 9, May 10, etc., with no chapter titles or headers. One day bleeds into the next into the next into the next. Inside the chapters, when I have to jump in space from one front to another, I tried drop-caps, and to create smaller pauses, I used asterisks. (My sense of rhythm in that regard is very influenced by the playwrighting of Nobel Laureate Harold Pinter. Ironic that Pinter and McCarthy, who had very different ideas of pacing, have both made such important impacts on my own pacing–but that’s a topic for another time!)

I hope the design of the book simultaneously captures that sense of unrelenting movement and activity while still being readable and attractive—perhaps mutually exclusive ideas in the world and writing of war.

————

A Tempest of Iron and Lead: Spotsylvania Court House, May 8–21, 1864 is available from Savas Beatie here.

Thank you for this post; not only for the information on the writing process itself, but also for highlighting the monstrous pace of movement and battle these armies faced. I believe that the latter parts of the Overland Campaign cannot be understood without realizing that both sides were completely exhausted to the point of illness. They were like two boxers clenching, too exhausted to throw any more punches.

Bully to you on the Tempest, looking forward to reading it twice. Enjoyed Jackson. Your tour-guiding of Spotsy was great this past summer. Reading Col. Wainwright’s diary about that May sometimes conveys the exhaustion feeling, his having to pull rank to get his artillery through traffic jams on muddy roads in the middle of the night to obey orders and be where he was told to be. If I had thought of the concept of trying to convey it through reading, maybe I would suggest channeling your inner Kate M Scott, consider a three-sentence page, all about the campaign’s non-stoppedness, with half a page run on sentence, followed by the short sentence, like, “They barely got a break.” Followed by another half page run on sentence?? But it’s a great point how it went on and on. When you work 7 days a week, you work 30 days a month.