Writing Tempest: The Challenge of Writing About Violence

Writing about violence poses a challenge for me, and that’s especially true when I write or recount the battle of Spotsylvania Court House. The battle ranked as one of the worst of the war, and the May 12 fighting at the Mule Shoe Salient was especially violent—sustained and violent.

Writing about violence poses a challenge for me, and that’s especially true when I write or recount the battle of Spotsylvania Court House. The battle ranked as one of the worst of the war, and the May 12 fighting at the Mule Shoe Salient was especially violent—sustained and violent.

And so, in A Tempest of Iron and Lead, this question of violence was something I wrestled with a lot.

Growing up, I hated slasher movies. I have a weak stomach for gore and grossness, and those movies were specifically designed to take those things to gratuitous extremes.

In my Civil War writing, though, I tend to favor accounts that graphically describe violence and its aftermath. I do so not out of some pornographic fascination but because, for too many people, the war’s violence has become abstract. They know, on an intellectual level, that war and battle and fighting all entail violence, but they have become inured to what that really means.

My intent is to reminder readers of the horror of war, whenever possible, using the words of the men who suffered through that violence.

This reminder is all the more important during a time when heated political rhetoric has made it easy for some people to threaten the idea of “civil war” in a far-too-casual way. We should never want it to happen again. We should never fall into the false belief that it’s inevitable and there’s nothing we can do.

Walt Whitman famously said the real war would never get in the books. There was too much, and too much of it was too terrible for words. People died in such horrible ways. “I never expect to be fully believed when I tell what I saw of the horrors of Spottsylvania, because I should be loth to believe it myself, were the case reversed,” wrote Federal officer Thomas Hyde.

Yet, if we don’t bear witness—responsibly, respectfully, honestly—we risk missing war’s most important lessons.

To strike the right balance, I needed to illuminate rather than force readers to avert their eyes. As uncomfortable as it might be—for writer as well as reader—we need to see.

————

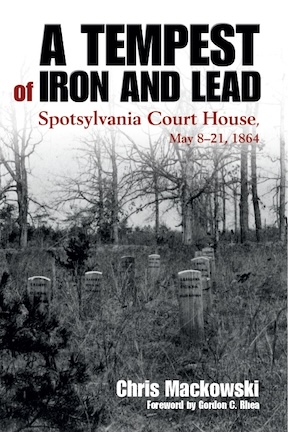

A Tempest of Iron and Lead: Spotsylvania Court House, May 8–21, 1864 is available from Savas Beatie here.

Which is why Ambrose Bierce’s Civil War writings remain among the best; honest truth-telling.

Given the close up nature of the violence, it’s easy to see how utterly brutal it is

And the wounds sustained were inconceivable. And I hated slasher movies as well.

After four years of reenacting during the Sesquicentennial, I became disenchanted with participating in the battle reenactments. By the time of the Bentonville reenactment in March of 2015 I could no longer point my musket directly at another human being dressed in a different color uniform and discharge a blank round, although four years earlier I was eager to experience what it was like on the firing line. Although the Epic continues to facinate, a sadness comes over me when the violence of which I read was necessary to guarantee that all men (and women) are created equal. However, I still have not reached the riverside and continue to study war. When will we ever learn, when will we ever learn?

You are correct; people have become inured to violence – too many movies and TV wars. And I too was never interested in slasher or horror films. It always troubled me that there were writers and directors who reveled in depicting innocent people’s pain and fear – and that people bought tickets to see it. The best way to write about violence in battle is to not say how terrible it was, but to show how terrible it was – use neither adjectives nor moral judgement – the writer does not have to think for the reader.

As noted in a previous email, please let me know how I can pose a research question to the forum.

I can certainly applaud your decision to focus on the violence, and for the exact reason you state: to make it perfectly plain how horrific war truly is. It’s all too easy to get drawn into ridiculous notions about the “romance” of war, like it’s some grand adventure and not the organized infliction of death on the largest scale possible. That’s why I’ve always appreciated Sherman’s attitude toward war — wage the damn thing hard and get it over with. It’s not a game.