The Gettysburg Gun

ECW welcomes guest author Stephen Evangelista.

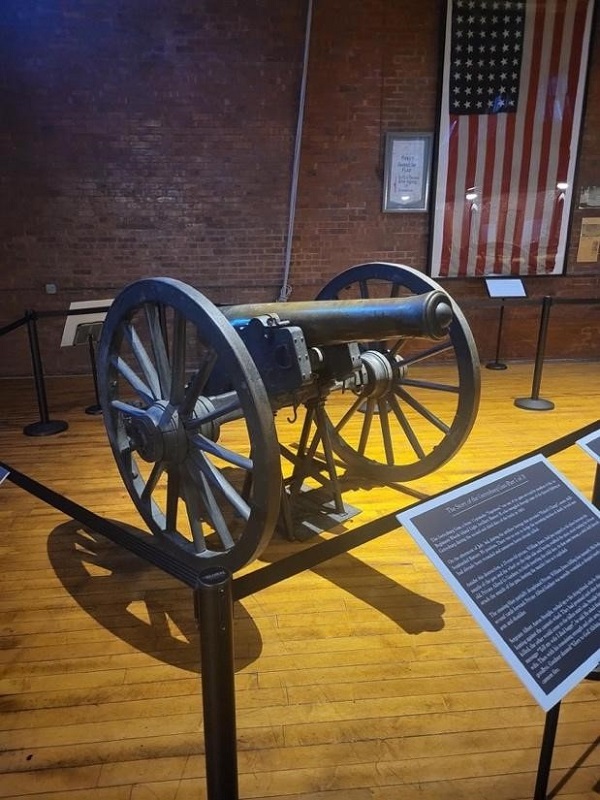

The Gettysburg Gun, a bronze 12-pounder Napoleon, was one of six cannon serviced by members of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, Battery B, who struggled through some of the fiercest fighting at Gettysburg during the second and third days of the battle in 1863.

On the afternoon of July 3, during the artillery barrage that preceded Pickett’s Charge, enemy shells bombarded Battery B’s position in the center of the Union line just south of the Copse of Trees. There was no way to dodge the incoming missiles of death. Several men had already been wounded and numerous horses killed.

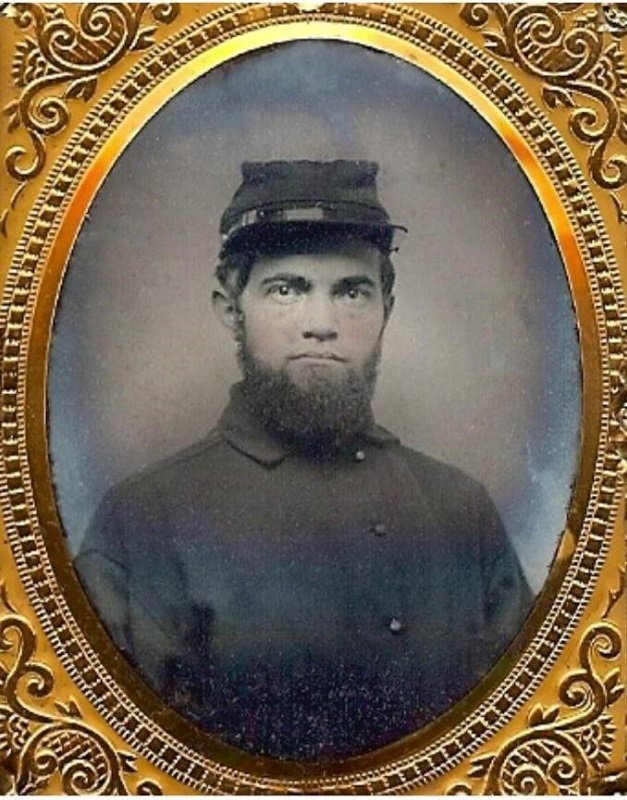

Amidst this destruction, 25-year-old Pvt. William Jones had just stepped to his place between the muzzle of the gun and the wheel on the right side and having swabbed the piece, stood waiting for 43-year-old Pvt. Alfred G. Gardner to finish inserting the solid shot. At that same instant, a rebel shell directly struck the muzzle of the gun, denting the muzzle’s face as it exploded.

The ensuing blast partially decapitated Jones, killing him instantly. His body was thrown several yards forward. Private Gardner was mortally wounded, as shrapnel nearly tore off his left arm and shoulder. Sergeant Albert Aaron Straight rushed up to his dying friend, who by this time was sitting on the ground leaning against the cannon’s wheel. They had promised each other that if one of them were wounded or killed, the other would come to the fallen man’s side. Straight listened as Alfred Gardner gave him a message: “Tell my wife I died happy”. He asked that Straight send his beloved bible home to his wife. Then with his remaining strength he reached out and shook Straight’s hand and said goodbye. Gardner shouted “Glory to God! Alleluia, I am happy. Amen!” and died amidst the roar of cannon fire.

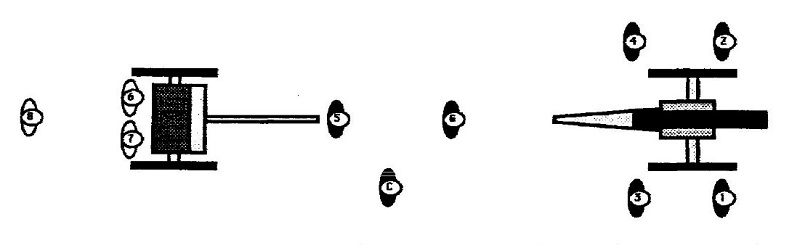

Sergeant Straight leapt to the front of the cannon in an attempt to reload it. With the number three man, who would normally tend the vent with a leather thumb stall, wounded, Cpl. Joseph M. Dye tore off a piece of his shirt, grabbed a rock, and laid it over the cannon’s open vent to prevent embers in the gun from igniting the next charge. Straight picked up the solid shot that Gardner had dropped. Knowing that the fixed ammunition charge would not get past the dent in the muzzle, he separated the powder bag from the sabot and rammed the powder bag down the barrel.[1]

Amidst flying bullets and exploding shells, Straight then attempted to ram the solid iron cannonball down the gun’s intensely hot barrel. Dye struggled to hold the ball in place as Straight swung the rammer, trying to force the projectile down the tube. Lieutenant Charles A. Brown shouted for someone to grab an axe from the caisson so Straight could force the projectile into the muzzle. But just as Straight was striking his target with the axe, another shell made a direct hit on the beleaguered gun, hitting the axle and putting a dent in it, knocking out a spoke, raising the gun on one side, and mortally wounding the number four man, 31-year-old John Greene. As these events transpired, the cannon barrel, now heated from heavy use, began to cool and permanently clamped down on the shot now stuck in the muzzle of the gun.[2]

At that moment, nearly ruined and out of ammunition, the Battery B cannoneers were quickly ordered to the Union rear. Through the heavy smoke and burning air, Confederate artillery officers witnessed Battery B’s withdrawal from the field. At the same time, Federal artillery fire began to slacken. The battery’s retreat to the rear had a dramatic effect even though they were now out of commission. Confederate generals believed that the Union line was pulling back and were convinced that the time had come to launch their grand ground assault, Pickett’s Charge.[3]

When the battle was over, the Gettysburg Gun had been riddled with 39 bullets and smashed three times by Confederate shells.[4] It was lost after the battle and then returned to its crew. The gun was broken, but not beaten, disabled, but not destroyed. In the end, it helped secure a piece of Rhode Island ground on Cemetery Ridge, fractured and fissured, but free.

After the battle, the Union Army condemned the piece and made plans to scrap the gun. The gun, however, was eventually put on display in the Washington, D.C. Navy Yard as a “Curiosity of War” until 1874. It was then that veterans of Battery B requested its return home to Rhode Island. The gun was brought back to Providence, Rhode Island where it was placed outside the old State House on Benefit Street. The battery’s veterans pridefully honored their piece with a parade and a grand military reception.[5]

For almost 100 years, the Gettysburg Gun stood watch over the north portico of the new State House on Smith Street in Providence, until a theory was brought forth that the cannon was still loaded with its original black powder charge. Mrs. Robert Dunn, of Coventry, presented a 1908 affidavit sworn to by her great uncle, Pvt. George R. Matteson, an original member of the Gettysburg Gun crew, which proved the theory.[6] On August 27, 1962, naval ordnance personnel aided by Rhode Island National Guardsmen, submerged the bronze tube in a tank of water and used a drill to widen the barrel’s vent hole. Using air and water pressure, they flushed more than two pounds of black powder from the gun’s barrel.[7]

The original Battery “B” continued to serve faithfully until it was mustered out of service on June 12, 1865. On May 21, 1874, the day the Gettysburg Gun came home to Rhode Island, Rev. Carlton A. Staples delivered the following prophetic remarks in his address:

“Take this gun, then and place it among the proudest archives of the State. Cherish it as a precious legacy from the men who bore it into the forefront of the battle and laid down their lives in serving it there. Tell your children and your children’s children the story of its triumph: a triumph not of men over men, but of truth over error; right over wrong; freedom over slavery … Though this gun be forever silenced, though its voice will never again be heard in thunders of war, yet it speaks to us and those who are to come after us in tones that cannot be misunderstood.”[8]

For over 160 years, the Gettysburg Gun has remained forever silent, but its story of survival and triumph echoes throughout the ages, reverberating the epic saga of those who so valiantly fought beside it and poured out their blood to protect the sacredness of a new nation.

Stephen G. Evangelista is a native New Englander who grew up in Johnston, Rhode Island and lives in Maryland with his wife and two children. He is a graduate of Providence College and serves as a member of the Senior Executive Service Corps in the United States Federal Government. He is an enthusiastic historian and member of the reactivated Battery B First Rhode Island Light Artillery.

Endnotes:

[1] John H. Rhodes, The History of Battery B, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery (Providence: Snow and Farnum, Printers, 1894), 208-216.

[2] Delevan, John. A Presentation at Gettysburg, July 2&3 1863. Courtesy of Battery B First Rhode Island Light Artillery Inc. Collection.

[3] http://npshistory.com/publications/civil_war_series/16/sec16.htm

[4] John H. Rhodes, The History of Battery B, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery (Providence: Snow and Farnum, Printers, 1894), 216

[5] John H. Rhodes, The Gettysburg Gun, Personal Narratives of the Events in the War of the Rebellion, Being Papers Read Before the Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society, Fourth Series-No.19 (The Providence Press: Snow and Farnham Printers, 37 Custom House Street, 1892), 29.

[6] George R. Matteson, Affidavit. 21 February 1908. Providence, Rhode Island. Courtesy of Battery B First Rhode Island Light Artillery Inc. Collection.

[7] The Providence Journal, County Edition, Volume CXXXIV No. 206, August 28, 1962, Pages 1, 9, 28.

[8] John H. Rhodes, The History of Battery B, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery, 388.

Excellent story.

An ineresting story, well-told.

The gun being served, not serviced, by its crew.

Glad you appreciated the story…

Indeed. I have one question – seriously – did CW artilleryman cover their ears when firing? We see this in films from WWI onward, though I’ve never seen it depicted in illustrations of the CW, or heard mention of it.

What a well researched, passionately written, rousing story!