The Ironclad St. Louis at Lucas Bend, Missouri

ECW welcomes back guest author Greg Wolk

The first time two ironclad warships battled each other was on March 9, 1862, at Hampton Roads in Virginia. A different question altogether is this: When did a United States ironclad vessel first come under enemy fire?[1]

James Buchanan Eads was the St. Louis engineer who conceived the City-class gunboats. In the autumn and winter of 1861-1862, Eads relentlessly pursued the construction and deployment of these ironclad behemoths of the inland waters, according to the design of naval architect Samuel Pook. He produced seven boats in this class: St. Louis, Carondelet, Cairo, Mound City, Cincinnati, Louisville, and Pittsburgh. Visitors to the Vicksburg National Military Park marvel at the sole surviving remnant of Eads’s fleet, the hulk of the resurrected USS Cairo. Eads, though, made it clear that if he had a favorite among the seven sisters, it was St. Louis. After all, she was the first City-class vessel launched, first commissioned, first outfitted and armed, and first to witness battle.

In September 1863, Eads penned a letter to President Abraham Lincoln. As shown on its face, the letter was motivated by Eads’s sense of loss after St. Louis went down in the Yazoo River the previous July.[2] In a sense, Eads was writing the boat’s obituary. He informed the president: “She [St. Louis] was the first armored vessel against which the fire of a hostile battery was directed on this continent; and so far as I can ascertain, she was the first iron clad that ever engaged a naval force in the world.”[3] While Eads’s memory of the events of January 1862 was not faultless, upon analysis it becomes clear that he makes reference to two separate incidents along the Mississippi River, both at a place 10 to 12 miles south of Cairo called Lucas Bend.

On January 11, 1862, the ironclad St. Louis lay at anchor three miles southeast of Cairo, at Fort Jefferson, Kentucky.[4] Docked alongside it was a former St. Louis ferry boat named USS Essex. Essex had undergone a transformation at Eads’s St. Louis shipyard, so like its City-class cousins it had the protection of iron plating. These two ironclads supported an infantry division that had just landed at Fort Jefferson. Under orders from Brig. Gen. Ulysses Grant, the army was tasked with launching a diversionary expedition into the interior of western Kentucky. The Union high command in Washington feared that Confederates were about to strike out from their position at Bowling Green, Kentucky (160 miles east) to attack Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio.[5]

At Fort Jefferson, news surfaced that armed Confederate vessels were steaming up the Mississippi from their base at Columbus, Kentucky. St. Louis and Essex cast off and headed south in a fog. At the head of Lucas Bend, the fog lifted to reveal a large enemy steamer, which fired a heavy shell in the direction of the Union ironclads. This large Confederate gunboat was soon joined by two others.[6] As reported the next day by Cmdr. William D. Porter, commanding Essex, the Union gunboats exchanged brisk fire with the three enemy vessels during a 20-minute running fight through Lucas Bend. General Grant, still in Cairo, reported the action to his superior officer in St. Louis, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck.[7]

Over the course of decades after the Civil War, the main channel of the Mississippi River slowly abandoned Lucas Bend. This oxbow, now nearly dry, still bears its historic name on topographic maps, even though the main channel finished the work of straightening itself at least 80 years ago. The head of the bend, at its north end, is seven river miles south of Fort Jefferson. The point where the dry bend now meets the modern channel is five miles south of there.

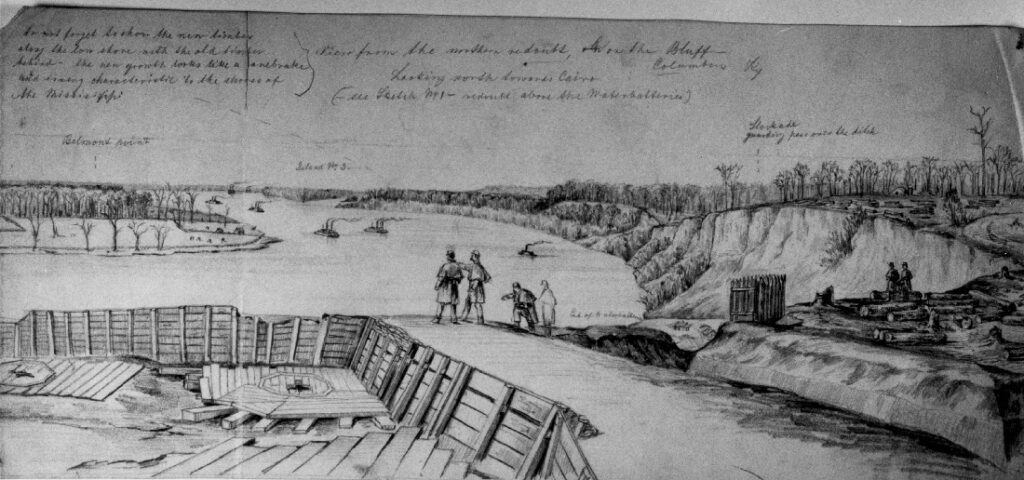

Significantly, in 1862 when Lucas Bend carried the main channel, the river made a sharp turn to the south in front of a 200-foot-high bluff. This feature, commonly known as the “Iron Banks,” stands north of the historic location of the town of Columbus, Kentucky.[8] Standing alone, the fortifications above Columbus presented a formidable obstacle to Union military operations. The existence of Lucas Bend, though, meant that southbound vessels had to expose their vulnerable bows as they turned to the right, and do it directly in the face of the powerful heavy guns at Columbus. It is no wonder that the Union Army never captured the Iron Banks by force of arms. Confederates abandoned this position in March 1862 after Grant’s breakthroughs at forts Henry and Donelson destroyed the defensive line they had established across Kentucky.

After the January 11 excursion, St. Louis and Essex withdrew to Fort Jefferson. On January 14, 1862 Grant joined Navy Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote aboard Essex, which became Foote’s flagship for a second reconnaissance of Lucas Bend. Once again, St. Louis joined Essex. Writing from Cairo upon his return that day, Grant notified St. Louis headquarters that the expedition went as close as a mile and a half from the Confederate batteries. Said Grant: “A few shells were thrown around the batteries by the Essex and St. Louis, with what effect I cannot tell. The enemy replied with two or three shots without effect.”[9] One must concede that this statement comports with James Eads’s memory. The shots from the Confederate battery, though they fell short, were directed at the ironclads in Lucas Bend.

Lucas Bend was not unfamiliar to Grant nor to Foote. On November 7 of the previous year Grant had landed 3,100 men on the south shore of Lucas Bend to fight at Belmont. Foote was in command of the naval element at the battle, although he was not there in person. As noted by military historian and professor Dr. Harry Laver, in an influential study of the history of joint operations in the U. S. military, then-Captain Foote first interacted with Grant on the heels of the Belmont battle.[10] Foote was livid. Grant had given Foote’s subordinate, Cmdr. Henry Walke, less than 12 hours’ notice that the operation would begin at 6:00 a.m. on November 7. Five transports and two timber-clad gunboats had to be readied, loaded, and coordinated. Foote was so upset that he wrote Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, demanding that Welles either send a naval officer with a rank higher than his who would have “immunity from the orders of a brigadier-general”[11] or that Welles appoint him to a naval rank that was equivalent to Grant’s. Foote was promoted to flag officer. The two men patched things up as they worked together over the next two months.

Meanwhile, Grant was involved in the first of his run-ins with his new commanding officer, Henry Halleck. It was Grant who, in the first instance, proposed that the new ironclads should steam up the Tennessee River to attack Confederate-held Fort Henry. Nine days after Grant and Foote’s trip to Lucas Bend, Grant traveled to St. Louis to present this proposal to Halleck in person. Halleck rejected the idea out of hand. The very next day, Grant telegraphed Halleck from Cairo, repeating the same proposal he had presented in person. This time it was different: Foote, by pre-arrangement with Grant, endorsed the proposal at the same time by separate telegram.[12] Halleck relented. The joint navy and army operation got underway on February 2. On February 6 Foote forced the surrender of the Fort Henry garrison.

The partnership forged by Grant and Foote produced victory after victory on the inland waters, culminating at Vicksburg, Mississippi. One imagines that this partnership was ‘sealed’ on January 14, 1862, during their joint expedition to Lucas Bend.

Mr. Wolk is a retired trial lawyer and writer. He serves on the Boards of Directors of the Jefferson Barracks Heritage Foundation and the National U. S. Grant Trail Association, both based in St. Louis. His works include Friend and Foe Alike: A Tour Guide to Missouri’s Civil War (Eureka, MO: Monograph Publishing Co., 2010), and numerous magazine articles focused on the Civil War in Missouri.

Endnotes

[1] The first ironclad in North America to do so was the Confederacy’s Manassas, at the battle of the Hear of Passes on October 12, 1861. Neil P. Chatelain, “Under Fire: First Ironclad Shots at the Head of Passes,” Emerging Civil War, October 12, 2021.

[2] St. Louis was re-named in 1863 when it was transferred from army to navy control. Henceforth it was USS Baron DeKalb. Eads to Lincoln, September 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833-1916, Library of Congress.

[3] Ibid.

[4] The Fort Jefferson site is a mile south of Wycliffe on U.S. Highway 51 in Ballard County, Kentucky. Founded in the Revolutionary War era by George Rogers Clark, it was re-activated at the time of the Civil War. Kentucky Historical Society, accessed 09/15/2024 at https://history.ky.gov/markers/fort-jefferson-site

[5] Ulysses S. Grant, The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1990), 189.

[6] The steamer that first confronted St. Louis at the head of Lucas Bend was Grampus, a converted side-wheeler that sported a pair of 12-pounder Napoleons. Neil P. Chatelain, “A Newly Uncovered Letter in the Most Ungentlemanly Porter-Miller Exchange,” Emerging Civil War, June 1, 2022.

[7] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume VII, 545 (hereinafter OR); Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series 1, Volume 22, 499.

[8] The bluff above Columbus is also known as the First Chickasaw Bluff.

[9] OR, Series 1, Volume VII, 551-552.

[10] Harry Laver, “Learning the Art of Joint Operations: Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy,” Joint Force Quarterly, Vol. 97, 2nd Quarter 2020, 103.

[11] Ibid, 104-105.

[12] OR, Series 1, Volume VII, 120-121.

Very nice and well-researched article on a little-known event. Greg is correct in his assessment of the USS Cairo as well. Well worth the visit while in Vicksburg. Thanks for sharing!