Confederate Guerrillas: Effective Commands or Detrimental Service? Part 2

Editor: Part 1 can be read here.

Guerrilla warfare, as viewed by the Confederate government as well as high-ranking commanding officers such as Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston, believed it “sapped strength from regular forces and often resulted in undisciplined bands that roamed the countryside victimizing civilians and bringing reprisals from Union forces.”1 In addition to these beliefs, the high command also noted that irregular commands were “frequently beyond the control of army, department or district commanders.”2

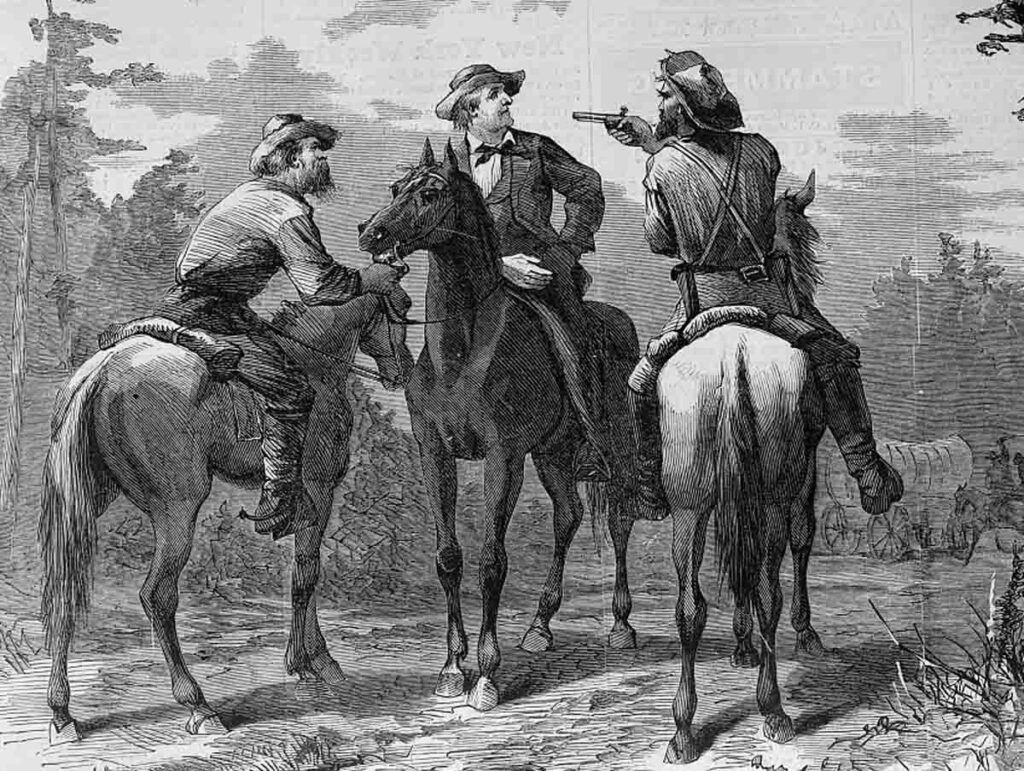

Because of this lack of officer control, regulations in place for plunder and other darker sides of warfare were left unchecked and utilized by those “who cared neither for cause nor country.” Unfortunately, their belief against these commands did not diminish their need for them as hordes of Yankee invaders crept into the geographic sphere of the Confederacy almost instantly after the first shots at Fort Sumter.

As advertisements for recruits for irregular, guerrilla, and partisan commands sprang up in southern newspapers, the Confederate government had to react. Reluctantly justifying these types of commands, the Richmond government said that they were comprised of “citizens of this Confederacy who have taken up arms to defend their homes and families.”3

In April 1862, partisan commands were officially enacted by the Confederate Congress. The new law stated that officers must be commissioned and paid by the Confederate government, and officers and enlisted men of these outfits were equal to troops in the regular Confederate armies. This law, although passed, did not quiet the debate over these commands, nor did it limit modifications to the enacted law.

With the official blessing of the Confederate government, limited as it proved to be, did the activities of these partisan commands such as Mosby’s Rangers positively or negatively affect the commands of not only their armies, but the enemy’s?

Mosby’s Rangers were successful on numerous occasions. During their 28 months of active operations they captured several ranking Union officers, numerous pounds of horseflesh, wagons full of supplies, damaged several miles of railroads, bridges, depots and telegraph lines, and took their fair number of Yankee soldiers out of commission for the rest of the war.

Mosby’s Confederacy, as it became known, incorporated the counties of Fauquier, Loudoun, Fairfax, and Prince William and provided not only food and shelter in numerous houses, but it also afforded known trails, roads, and escapes routes which to deliver battle and operations. One example of their success was the “Berryville Wagon Train Raid,” where the Rangers captured nearly 200 beef cattle, 100 wagons, 500 to 600 horse and mules, and nearly 200 prisoners.4

Even towards the fading autumn of 1864, historian Jeffery Wert noted their success against Mosby’s newest nemesis and enemy. “In a month of campaigning against Sheridan’s army, Mosby and the Rangers had fared well….[As] the gains far outweighed the price.”5 Mosby’s successes and his strict command style of his partisans spared their disillusion when the Confederate government reversed their 1862 enactment. In February 1864, Robert E. Lee came to Mosby’s and his irregular unit’s defense by stating, “I recommend that this battalion be retained as partisans for the present. Lt Col Mosby has done excellent service, & from the reports of citizens & others I am inclined to believe that he is strict in discipline & a protection of the county in which he operates.”6

Lee firmly believed that only Mosby’s battalion be kept on the roles and that all other partisan commands in Virginia be disbanded as they are “a haven for marauders and deserters and an enticement for regular army troops ‘to leave their commands.’”7 In these events and situations, Mosby was a positive influence on the Army of Northern Virginia and a negative impact on the several Union armies the area, including the Army of the Potomac. Mosby, however, did take losses as well and was affected negatively by those losses both as a commander and by the Army of the Potomac.

One negative aspect of irregular or guerrilla warfare was retribution or revenge, especially to those who harbored these fighters. Mosby’s command was no different, and this was just one negative facet that affected his own command and the army. After one Federal raid in response to Mosby’s activities, one diarist said that the local citizens were “terrified,” while another writer, “believed that the Yankees would return again and again to protect their camps and outposts….”8

Historian Jeffery Wert commented, “The[se] raids into Mosby’s base had netted prisoners and taught the civilians the costs that could accrue for their support of the guerrillas.”9 On a myriad of other retaliatory raids, Union troops seized every horse they could find, arrested all male citizens for miles, and confiscated food and goods from private homes in the area. Later in their campaigns, some of Mosby’s men were even executed by gunpoint and hanging all as retaliatory measures against the raiders.

As well as this price to be paid, raiders across the South faced defeats against their Union foe in battle. For Mosby’s men, their defeats were met at Warrenton Junction, Grapewood Farm, and Loudoun Heights to name a few.

Also negatively affecting the Confederate command and armies in the field was exactly what the Confederate government feared, plundering and other cruel acts against its citizens by the irregulars; Mosby’s command was no exception. When Mosby was seriously wounded and disabled for close to a month, numerous Rangers combed his Confederacy in the search of wagons full of goods. “The operations, in Mosby’s absence, had little military value. Plunder seemed to be the guiding motive.”10

With both the positive and negative impacts on both their own armies and commands, and that of their enemies, were men like Mosby able to directly affect operations of those respective forces?

There is little doubt from the pages of history that Mosby’s command was able to achieve a degree of success in what he did. Many other partisan commands simply did not have the quality of men or control needed over those men to achieve what the Rangers had done in northern Virginia.

Despite these successes, however, and the praise of both J.E.B. Stuart and Robert E. Lee, Mosby was only able to affect limited operations in his sphere of influence. He was not able to completely stop Union armies from moving through his Confederacy, nor was he able to keep them out altogether. The successes he had in captured supplies and horseflesh, although substantial over the two-year time span, was not nearly enough to slow down or stop the overwhelmingly supplied northern armies and their continual shipments of supplies.

Mosby’s force, although successful in several engagements with Union cavalry, also suffered its share of defeats. His force was not large enough, even at its peak, to be able to confront massive amounts of Union cavalry, let alone Union infantry that began to accompany supply trains, wagons, communication lines, and more. In addition to these inadequacies, and despite Stuart and Lee’s praise and reassurance to the contrary, Mosby’s operations never pulled enough troops away from the eastern front to help balance Lee’s inferior numbers versus the Union army.

For all of his successes, as well as failures, Mosby’s men were not able to significantly affect the bigger picture when it came to operations in the East, nor were any other partisan commands throughout the Confederacy. Nevertheless, it was Ulysses S. Grant that said of Mosby, “There were probably few men in the South who could have commanded successfully a separate detachment in the rear of an opposing army, and so near the border of hostilities, as long as he did without losing his entire command.”11

1 Jeffery D. Wert, Mosby’s Rangers: From the High Tide of the Confederacy to the Last Days at Appomattox – The Story of the Most Famous command of the Civil War and its Legendary Leader, John S. Mosby (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 70.

2 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 70.

3 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 70.

4 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 192.

5 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 199.

6 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 157.

7 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 157.

8 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 55.

9 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 66.

10 Wert, Mosby’s Rangers, 96.

11 Wilmer L. Jones, Behind Enemy Lines: Civil War Spies, Raiders, and Guerrillas (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 2001), 127.