Exchanging Insults Rather Than Soldiers: Solomon Meredith, Robert Ould and the Breakdown of the Civil War Prisoner Exchange System (Part II)

The question closing Part I of this post was: “Would such vitriol continue, or would the two men [Solomon Meredith and Robert Ould] pull back from their personal differences and focus on the plight of the unfortunate POWs held by each side?”

The vitriol continued. Indeed, Meredith poured on the venom in fullest measure. By letter of November 14, Meredith replied to Ould’s October 31 letter, stating that he “would have been surprised at its contents had I not been previously acquainted with your habit of special pleading and of perverting the truth.” Meredith sarcastically taunted Ould, writing that of course “a Government in as prosperous a condition as the Confederacy, with men in superabundance to put into the field,” would not need to break exchange rules. “[N]or would a high-toned, honorable gentleman…” do so in order to reinforce the rebel force at Chickamauga. Meredith claimed that “your principles are so flexible and your rule of action so slightly influenced by a sense of truth, honesty, or honor” that it precluded any fair agreement, concluding that Ould was “utterly reckless of integrity and fairness… in your declarations of exchange.…” [1]

Not surprisingly, Ould showed no interest in lowering the temperature. Moreover, the poison spilled over into issues other than POW exchanges. On November 14, Ould refused to deliver a letter from Meredith to a U.S. officer held in Richmond’s Libby Prison. Therein, Meredith advised that he was sending by flag of truce 24,000 rations for distribution to the suffering Union POWs, asking the officer to oversee the process. Ould snottily returned the letter, telling Meredith that the Confederates would decide how to distribute the rations, and “If you are not satisfied with these regulations you can take back your rations and withhold any in the future.” [2]

Around this time a new name started appearing in POW-related correspondence. Major General Benjamin F. Butler had assumed command of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, headquartered at Fort Monroe.[3] On November 17 Butler wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, stating that he had heard that the rebels were willing to resume exchanging POWs, and asking if he personally should follow up. Stanton replied that Maj. Gen. Ethan Allan Hitchcock (Meredith’s direct superior) oversaw exchange issues. Stanton added that Confederate refusal to exchange black troops or their white officers was the obstacle to resumption of exchange. [4]

Butler replied the next day. [5] While admitting that he was stepping outside of his responsibilities, Butler—who clearly had examined the Meredith-Ould correspondence—insisted that the Confederates repeatedly had offered to exchange POWs without mentioning any exception with regard to color. Butler observed that rather than following up on this promising proposal, dispute had broken out on other issues. Butler opined that the poisonous relationship between Meredith and Ould was causing them to forget their duty, writing: “It would seem that the discussion had grown sufficiently acrimonious to have lost sight of the point of dispute….” While Butler assured Stanton “I do not mean to impute blame to any party,” he stressed that Union POWs starved while the exchange commissioners argued with each other.

Butler had an idea. He noted that the U.S. held more rebel POWs than the Confederates had U.S. soldiers. If an exchange revealed that black troops had been withheld, retaliation could be inflicted upon the remaining rebel POWs. In again urging action, Butler now did tacitly blame Meredith, at least in part, for the impasse:

“Without suggesting any blame upon the part of the agent of exchange [Meredith], would not the fact seem to be that such a state of feeling has grown up between himself and the rebel agent, that, without doing anything which would impute wrong or detract from the appreciation of the efforts of General Meredith, this might be done as if outside of either agent?”

Hitchcock saw Butler’s letter suggesting bypassing Meredith. He wrote Stanton on November 24 to correct Butler, noting that Ould’s proposal was that both sides release all POWs, meaning that the large POW excess held by the Union (some 27,000) would come into Ould’s hands.[6] Then, Hitchcock assured Stanton, Ould would craft some theory to justify their return to the ranks. Moreover, Hitchcock presented evidence that the Confederates were claiming that they did not hold any black POWs by ensuring that they were sent to Confederate states for imprisonment in penitentiaries, sold into slavery, or simply murdered. [7]

Hitchcock’s description of Ould’s position promptly was validated. On November 25, Meredith reported that he had made an “unofficial” proposal to Ould, specifically, that each side exchange 12,000 POWs. [8] Ould rejected the idea, insisting that all Confederate POWs be released into his custody.[9]

Nevertheless, Butler continued to inject himself into POW issues. On December 7, on his own authority he sent smallpox vaccine to Ould for administration to federal POWs to combat an outbreak of the disease. Ould responded courteously. [10]

Butler’s machinations ultimately worked. On December 16, Stanton ordered Hitchcock to confer with Butler on POW issues. Hitchcock was authorized to deputize Butler to act directly on such issues. Stanton added, in what was probably a hint, that Hitchcock was authorized to, “if you deem it proper, relieve General Meredith.” [11] The next day, Hitchcock appointed Butler “special agent for exchange of prisoners of war at City Point,” placing Meredith under Butler’s command.[12] Meredith’s career in the prisoner business ended completely on December 25, when Butler relieved him as a commissioner of exchange. [13] The next month Butler ordered Meredith out of his department. [14]

What accounts for Meredith’s ignominious end? Hitchcock blamed Butler’s scheming. In a lengthy March 3, 1864 missive to Stanton, Hitchcock asserted that in his eagerness to assume the role of savior of Union POWs and thereby win plaudits from the Northern public, Butler had busied himself “casting unworthy imputations upon his predecessor, General Meredith.…” [15]

Hitchcock did not detail what Butler said of Meredith. Yet the nature of Butler’s criticism can be gleaned from his correspondence to Stanton blaming the breakdown of negotiations on the animus that had arisen between Meredith and Ould. Indeed, Hitchcock conceded that their poisonous relationship was blocking progress. In his March 3 letter, Hitchcock reminded Stanton “that when it became apparent that the system of exchanges had become seriously interrupted to the prejudice of our prisoners in Richmond,” Hitchcock had offered to resign. Hitchcock admitted that the reason for his offer was that “the unpleasant controversy between [Ould] and General Meredith … made further exchanges apparently impossible without a change of agents.”[16]

Ould agreed that his relationship with Meredith had become so toxic as to preclude cooperation. In writing post-war on the exchange system, and discussing the effect of Butler’s appearance on the scene, Ould noted that “… I was confident that General Butler and I could discuss controverted questions in better temper than General Meredith … and myself had manifested.”[17] Indeed, Ould proclaimed that of all the exchange representatives with whom he had dealt, Butler “… was the fairest and the most truthful. The distance between him and Hitchcock in these respects was almost infinite.”[18]

Ould characterized Meredith as Hitchcock’s “supple tool,” pointedly contrasting Meredith with his predecessor Lt. Col. William H. Ludlow, whom Ould considered “courteous and just.” [19] Ould’s distaste for Meredith went beyond simply deeming him a willing “tool.” Convinced that Meredith’s mission was to abort the exchange system, Ould felt that “[Meredith] abounded in all the qualities which would make him useful on just such a service. He was coarse, rude, arrogant, and so unacquainted with the matters committed to his charge, that it was difficult to transact any business with him.” [20] As shown, Meredith similarly held Ould in low regard, deeming him an untrusty man of no honor. Their contempt for one another shone through in their bitter, insult-filled, correspondence.

With a relationship so fraught not only with mutual distrust but personal distaste, it is understandable that the prisoner exchange system, already facing serious challenge due to multiple complex issues, broke down so completely that even Hitchcock recognized that a change in personnel was needed. Enter Butler.

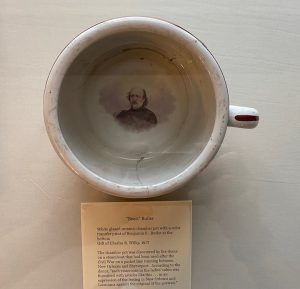

Butler seemed a particularly inappropriate choice for a role requiring direct dealing, not to mention diplomacy, with Confederate agents. In December 1862 Confederate President Jefferson Davis had issued a proclamation calling for the summary execution upon capture of the “outlaw and common enemy of mankind” Benjamin “Beast” Butler for hanging a New Orleans civilian, for his issuance of General Orders No. 28 (the infamous “women’s order”), and other alleged outrages.[21] The Confederates could hardly be expected even to communicate with Butler, let alone work with him.

How would Butler handle this challenge? Only time (and a future blog post) would tell.

[1] OR, 504-507.

[2] OR, 503, 522.

[3] Mark M. Boatner, Civil War Dictionary, p. 109 (David McKay Company, Inc., New York, NY, 1988).

[4] OR, 528.

[5] OR, 532-534.

[6] At this point, the U.S. held about 40,000 Confederate POWs; the CSA had about 13,000 Union POWs. OR, 597-598, 599.

[7] OR, 556-557.

[8] OR, 565-566.

[9] Ould claimed that the “cardinal principle” of the Cartel was its requirement that all prisoners be exchanged “within ten days after their capture.” OR, 921-922. Ould would not accept half-a-loaf.

[10] OR, 658-659, 683.

[11] OR, 709.

[12] OR, 711-712.

[13] OR, 757.

[14] OR, 874.

[15] OR, 1007-1013.

[16] OR, 1010 (emphasis supplied).

[17] Judge Robert Ould, “The Exchange of Prisoners,” The Annals of the Civil War: Written by Leading Participants North and South, Alexander Kelly McClure, Ed., p. 42 (The Times Publishing Company, Philadelphia, PA, 1879), https://www.pedseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0012%3Achapter%3D3%3Apage%3D32.

[18] Ould, p. 43 (emphasis supplied).

[19] Ould, p. 57.

[20] Ould, p. 58.

[21] OR, Series I, Vol. XV, pp. 905-908; Christopher G. Pena, General Butler, Beast or Patriot, New Orleans Occupation, May-December 1862, pp. 78-83, 86-87 (1st Books, Bloomington, IN, 2003).

Good article. The question is, why did the exchange system continue to work in the Trans-Mississippi? There were the following. 1. Exchange pursuant to Article 7 of the Cartel for the Bayou Bourbeau prisoners in December 1863. 2. Exchange from Camp Ford, including two white officers of black troops, on July 22, 1864. ( A white surgeon of a black regiment, David Hershey, captured at Brashear City in June 1863 was released pursuant to an agreement between the agents that surgeons were not be held as POW’s. 3, Exchange of prisoners from Camp Ford on October 22, 1864. 3. Parole (not exchange) of all prisoners from Camp Groce at Galveston, December 1864. 4. Exchange of all naval Prisoners from Camp Ford, February 23, 1865. (The most US Naval Prisoners in the war were taken in the Trans-Mississippi) 5. Final exchange from Camp Ford on May 22, 1865. Perhaps it is the fact that Kirby Smith was virtually autonomous and the fact that the Union agents were willing to bend if not actually break the rules, and ignore the 30 or so free black naval prisoners and 80 men of the 1st Arkansas, African descent who were prisoners but held to labor.

It is my impression that the real difference was the fact that in the TM, the agents for both sides were extremely civil to each other. However, I cannot find where anyone other than me has ever looked at the exchange in the west. Your comments and observations would be appreciated. Obviously, I can footnote all of this.