Willis Cole, the Battle of Bentonville, and the Southern Claims Commission, Part 1

ECW welcomes guest author Derrick S. Brown.

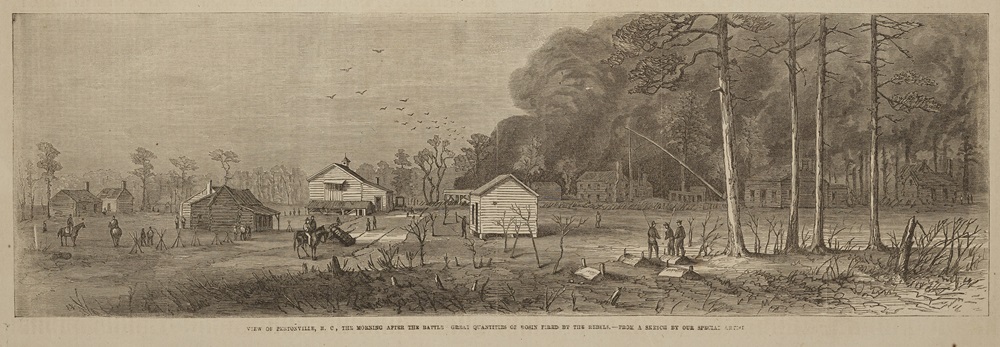

When the last of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s veterans departed Bentonville, North Carolina on March 22, 1865, much of the village and the community at large was left a smoldering ruin. After the Confederate withdrawal on the night of March 21, the mutilated corpses of several Union soldiers were found near the small village. In retaliation, angry Federals set fire to Bentonville’s turpentine distillery and carriage shop. The homes of Reverend John J. Harper and several other Bentonville residents were also put to the torch – quite unfairly, at least in Harper’s case, as repatriated wounded Union prisoners of war soon spread the word that he had nursed them throughout the battle.[1]

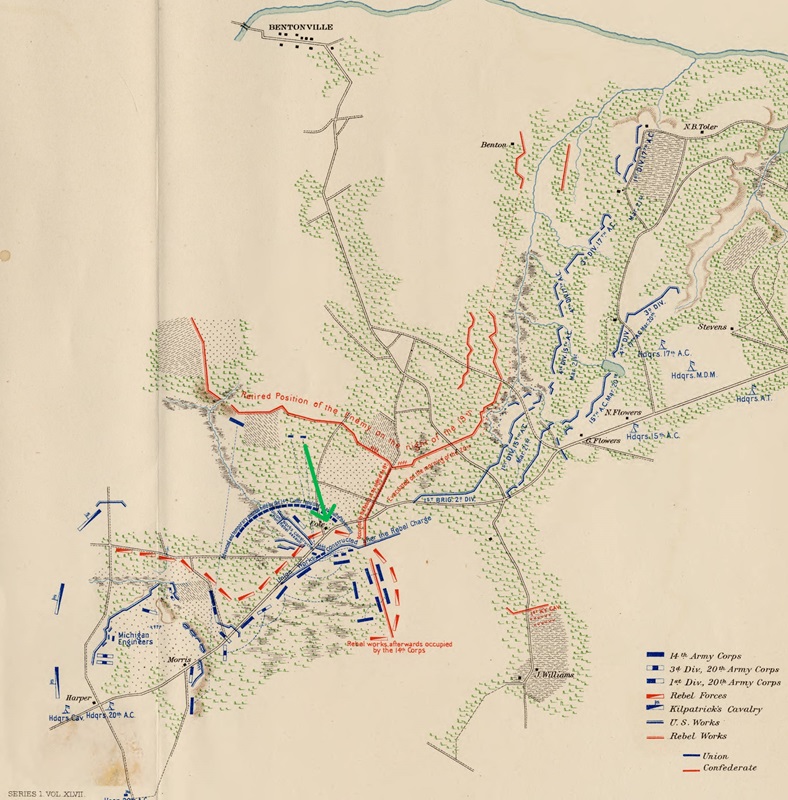

Willis Cole Jr., who lived three miles south of Bentonville, also lost his home to fire. Cole’s plantation was chosen on March 18 by Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton as a suitable place for Gen. Joseph Johnston’s Army of the South to ambush an isolated portion of Sherman’s command the next day. Before the major Confederate assault on March 19, the Cole house and buildings were overrun and occupied by the 33rd Ohio, as it provided them some protection from the North Carolina Junior Reserves who were randomly firing at the exposed Buckeye soldiers. In response a Confederate battery opened on the house with their Napoleons which, according to one witness, caused “the Yankees to pour out like rats out of a sinking ship.”[2]

On March 21, the battle’s final day, Union sharpshooters drove off Confederate pickets from the area around the house so that they could use the upstairs for long-range sniping. Consequently, Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill ordered the Army of Tennessee’s skirmishers to retake the home and then to burn it and its attending buildings to the ground. At battle’s end one witness recalled seeing the plantation “swept just as clean as a field – not a fence, house, dwelling house, or anything was left – nothing.”[3]

Willis Cole Jr. was born in 1830 in the Bentonville community, the son of Willis Cole and his first wife, who likely passed during childbirth. In 1836 the elder Cole married Mary Flowers, who gave Willis Sr. another son in 1840, named William “Bright” Cole.

In 1857 the younger Willis married Caroline Stevens, the modestly affluent widow of John Cogdell. Whether through these connections or by some other means, Willis Jr.’s wealth had far outstripped his father’s holdings by 1860. Willis and Caroline lived on a 2,200-acre plantation, where they enslaved twenty-three people who inhabited seven dwellings on the property.[4]

Cole’s stepson, William Cogdell, and his half-brother, Bright, enlisted in the Confederate army in 1861. Cogdell was still a teenager when he died the following year from typhoid fever. Bright was captured at Fort Macon in April 1862, but was exchanged that summer. He was wounded during the first battle of Fort Fisher in December 1864 and captured again when the fort fell the following month. Bright’s second capture resulted in a trip to the prisoner-of-war facility at Point Lookout, Maryland before a transfer to Elmira, New York.[5]

Unlike his stepson and half-brother, Willis Cole never enlisted in the Confederate army. He circumvented the 1862 Conscription Act by hiring a substitute, but this exemption was eliminated in 1864 by the Second Conscription Act.

But even the more stringent version of the act excluded local authorities responsible for preserving law and order. To capitalize on this loophole, Cole’s friend William A. Smith, a member of the state legislature (and a future U.S. congressman), arranged for Willis to be appointed as a magistrate. Cole remained exempt, but eyebrows were raised when it was revealed that he was functionally illiterate. He was never sworn into this post because he could barely sign his own name.[6]

Because of its strategic location at the intersection of the Averasboro-Goldsboro Road with the road to Smithfield, Cole’s plantation became the lynchpin of Confederate efforts to defeat one of Sherman’s “wings” before they could reach reinforcements and resupply in Goldsboro. A seventeen-mile overnight march from Smithfield allowed much of Johnston’s 20,000-man army to join Hampton on the plantation by midmorning on March 19. By noon, the largest and bloodiest battle ever fought in North Carolina raged on Cole’s property.

The Cole family did not witness the battle because they were ordered to leave for their own safety. According to Cole, Hampton threatened to arrest him for not serving in the army, which may have expedited the family’s departure. When they returned on March 22, they found their home and much of their possessions gone. They did find Union soldiers feverishly burying the dead and loading up the wounded so that they could depart for Goldsboro later that day. Also likely gone were the nearly two dozen enslaved people who lived on the plantation. Those that had not been impressed into Confederate service were emancipated by the Federals.[7]

Bentonville proved to be the final battle between the two principal Western Theater armies. In fact, the war all but ended with Johnston’s surrender to Sherman five weeks later.

Though no doubt grateful that the conflict was over, Cole found himself as impoverished by the war and subsequent Reconstruction era as his pro-Confederate neighbors. Fortunately, Cole had his wife’s property – located in Grantham Township in neighboring Wayne County – to move his family to. Financial hardship may not have been the only reason that Cole chose to move instead of rebuilding. Intended or not, the move put a healthy distance between Willis and Bentonville’s returning Confederate veterans, such as his half-brother Bright.[8]

In the war’s aftermath the initial slate of U.S. congressmen from former Confederate states were overwhelmingly from the Republican Party. Many of these politicians were Unionist during the war, and some had suffered great losses at the hands of their liberators. To compensate and reward these loyalists, Southern and moderate Northern Republicans banded with reconciliationist Democrats to pass a law in 1871 establishing the Southern Claims Commission (SCC). Its goal was to reimburse Unionists whose goods were officially requisitioned or destroyed by the U.S. military during the war. Congress authorized President Ulysses S. Grant to choose three commissioners who were granted broad plenipotentiary power to control the eligibility for claimants. Judge Asa Owen Aldis of Vermont (president) and two former congressmen, Orange Ferriss of New York and James B. Howell of Iowa, were appointed. All three held solid Republican Party credentials.[9]

To preempt fraud, the commissioners created strict parameters for claimants. Reimbursement was for quartermaster or commissary supplies only, not for damaged or destroyed buildings. Furthermore, it had to be proven that an officer had ordered items to be confiscated for official use. Damages caused by rogue Federal soldiers were not deemed the responsibility of the government and were thus not eligible for reimbursement. All approved claims were subject to congressional review since Congress was responsible for appropriating money for payments.[10]

The biggest obstacle for many claimants was proving their unwavering loyalty during the war. To establish this fact, “Standing Interrogatories” were created by the commissioners to weed out those who rendered even the smallest amount of aid to the Confederacy. In 1871 claimants were asked approximately 50 questions, a number that grew to over 80 by 1880. Question 32, for example, asked, “Have you ever given aid and comfort to the rebellion? If so, state fully all the circumstances.” This aid could have been something as simple as sending your conscripted son a pair of socks. Despite the high threshold of proof needed for a claim, Willis began the process in 1872.[11]

Be on the lookout for Pt. 2 to see if Willis was successful.

Derrick S. Brown is the operations manager at the Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site.

————

Endnotes:

[1] Battle Incidents Come to Mind, Smithfield (NC) Herald, September 13, 1927.

[2] Mark L. Bradley, Last Stand in the Carolinas: The Battle of Bentonville (Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury, 1996), 163.

[3] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 47, pt.1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1895), 1092; Cole, Willis in US, Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims, 1871-1880, 42. Records Group 217, US National Archives.

[4] Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860; The Cole family genealogist has not uncovered the name of Willis Sr.’s first wife.

[5] Historical Data Systems, “William B. Cole,” accessed November 12, 2024, www.civilwardata.com.

[6] Cole, Willis in Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims, 1871-1880, 3.

[7] Cole, Willis in Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims, 1871-1880, 4; many descendants of enslaved people on the Cole plantation remain in Bentonville today.

[8] Reddick Morris, another alleged Unionist, also fled Bentonville. These decisions may not have been coincidental.

[9] Susanna Michele Lee, “The Southern Claims Commission in Virginia.” Retrieved from https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/southern-claims-commission-in-virginia-the/ ;in some cases it was the congressmen themselves who unblushingly qualified for compensation.

[10] Lee, “The Southern Claims Commission in Virginia.”

[11] Lee, “The Southern Claims Commission in Virginia.”

Enjoyed the post!

Would you be able to tell me what happened to the confederate soldiers that surrendered at Bentonville?