Gulf of Mexico / Gulf of America: Highlighting Civil War Era Location Literacy

On January 20, 2025, newly sworn-in President Donald Trump signed an executive order to rename “the area formerly known as the Gulf of Mexico” as the “Gulf of America”[1] Whether such a renaming is warranted, and whether it will remain in the long-term, is debatable, and not something I will address here today. Instead, I will look at Civil War era ties to name changes, how historians and others have adjusted to using them, and why knowing what things were called in the 1860’s is important to studying the war.

Studying the Civil War era means you will inevitably run into some inconsistencies with how things were 160 years ago and how things are today. Of course, the technology is different, laws have advanced, and people spoke with certain colloquialisms. Understanding word choice of the Civil War is critical to understanding the conflict itself. Civil War enthusiasts and historians alike are aware that the United States and Confederacy often named battles differently (Bull Run vs. Manassas). Another great overall example of this is names of cities. These urban centers were the critical focal points for government and industrial activity, but naming conventions for some cities can get confusing. Let’s unpack a few examples.

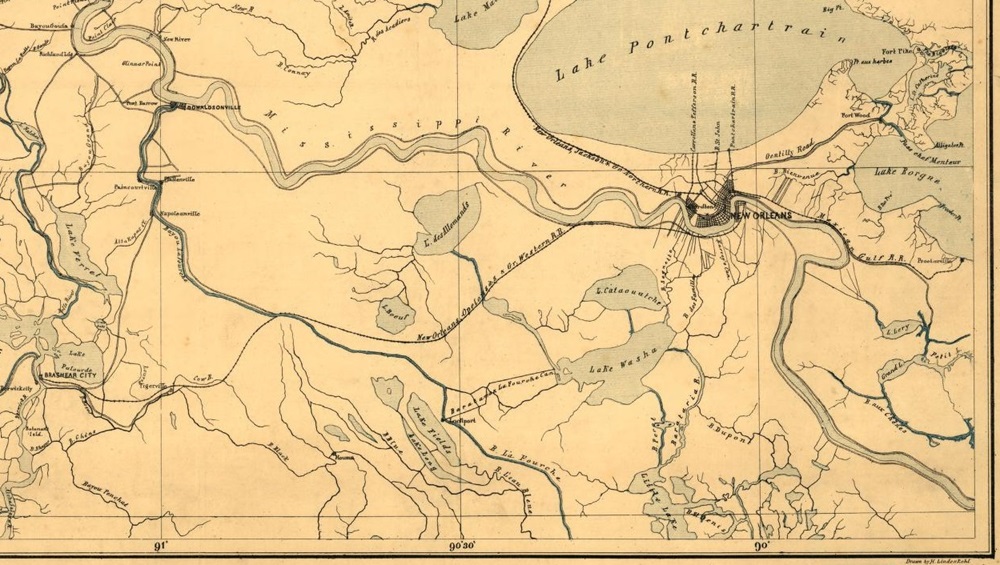

There are many cities from the Civil War era with different names today. I have encountered some of these in my own research; two worth mentioning are the Louisiana urban centers Vermilionville and Brashear City. Vermilionville changed its name to Lafayette (to honor the Marquis de Lafayette) in 1884, meaning that anyone studying Civil War documents must be familiar with the original name to fully comprehend what they may be analyzing.[2]

The same issue pervades when looking at activity in Brashear City, Louisiana. This town even had several military engagements during the Civil War and could be called the ‘Winchester’ of Louisiana because of how many times it changed hands because of shifting armies. Before the Civil War, Brashear City was occasionally called Tiger Island, and after the war in 1876, it was changed again to Morgan City, honoring Charles Morgan, the tycoon who operated the Southern Steamship Company.[3] Other examples exist, such as how the battle of Kennesaw Mountain was fought near the town of Big Shanty, which was later renamed Kennesaw postwar.[4]

Other cities did not change their name after the Civil War, but had their name fought over during the conflict itself. The best example I can provide is the city of Colón, which during the Civil War was part of the United States of Colombia (today in Panamá). The city was established by American businessman William H. Aspinwall, who built the Panama Railroad across the isthmus as part of the Panamá route. Before Aspinwall’s engineers began work building the city, Colombian officials established that the settlement would be called Colón, but once work commenced, everyone locally began calling it Aspinwall. This double-name issue continued through the Civil War and was only settled after local postal officers refused to deliver any mail to the town if the name Aspinwall was used. Thus, wartime documents use both names interchangeably, with most Americans using Aspinwall (hinting at U.S. influence in Latin America) and most locals and Europeans using Colón.[5]

Another aspect of urban literacy worth mentioning is that the boundaries of cities were different 160 years ago. Many places that are part of cities today were separate political entities during the Civil War. For example, Brooklyn was a separate city from New York City during the war. The city of Carrollton, which today is a part of New Orleans, was a separate entity. Both Carrollton and Brookyln even had their own newspapers to mark their distinction.[6] Being wary of these differences can help researchers when looking at period records, and it can help everyone better understand what they are reading. This distinction goes beyond cities, lest we forget that several territories shifted to statehood during the Civil War (or the complexities surrounding the invention of West Virginia or division of New Mexico/Arizona).

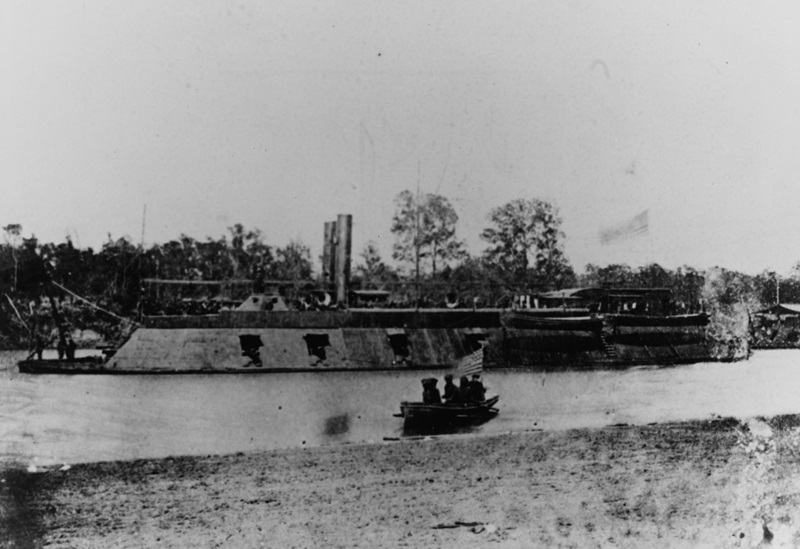

A final example of urban center naming conventions surrounds Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. During the war, the city included its ‘h’ at the end of its name, but from 1891-1911, the U.S. Board of Geographic Names (an organization mentioned in President Trump’s executive order) standardized spelling of city names where all cities ending in -burgh or -burg would all end in -burg. This was the same time that the Official Records were being compiled, so all mentions to the city of Pittsburgh, or the U.S. ironclad Pittsburgh, are instead spelled Pittsburg in the OR and ORN, causing most secondary works to continue using the -burg spelling even though in the 1860’s the city and ship ended with -burgh.[7]

Besides cities, other organizations also changed their names. Sometimes ships captured by the opposing side had their names changed, such as the steamer Star of the West. Sometimes ships were just called different names for no apparent reason (some U.S. sailors called CSS Manassas the ironclad Bull Run instead). Sometimes, both sides had ships with the same name (such as Carondelet or Alabama). Military units also changed their names and designations, especially when regiments were consolidated (the Louisiana Native Guards changed to the Corps d’Afrique and then to standard numbered USCI regiments).[8] Keeping this all together can be confusing, but is essential to properly reading original documents and contextualizing original source material.

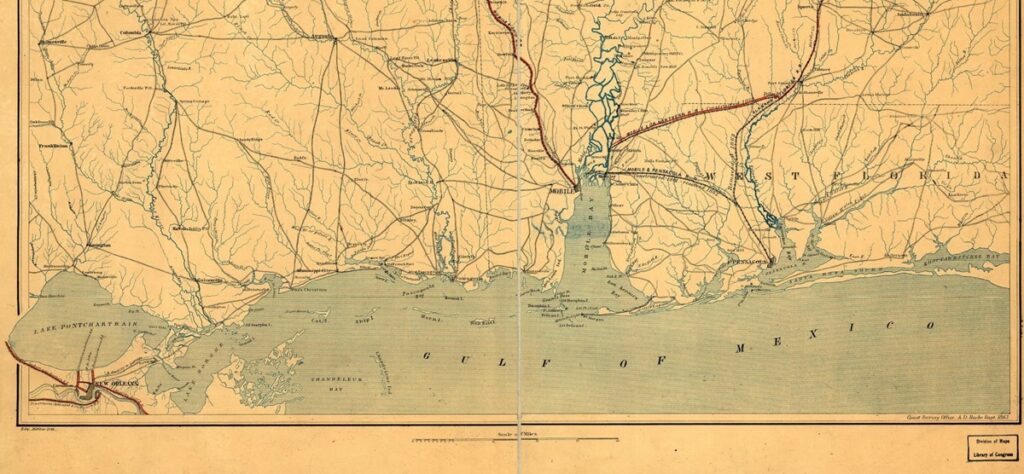

Though everyone today knows what a map labelled Gulf of Mexico means, Civil War historians and enthusiasts will now need address the body of water’s name. During the Civil War, the body of water was called the Gulf of Mexico. Will historians writing about the 19th century continue calling it that, as those writing at the time did, or will terminology change over time? Will we instead need to adjust our word choice as has occurred before (i.e. slave vs enslaved)? Will it all be ignored, with the U.S. government’s naming conventions shifting back to Gulf of Mexico eventually? Time will tell as individual historians, publishers, and editors process everything and begin making decisions regarding their word choice and style guides. I use the names, locations, and organizations of cities from the time, but others may not.

One final note. These conventions and adjustments are just a handful of examples about how being more literate in names of urban centers (and other things) during the Civil War can help better understand the conflict. There are certainly many more. Feel free to add your own examples of cities, organizations, battles, and everything else into the comments section below.

Endnotes:

[1] Donald J. Trump, “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness,” Executive Order, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/restoring-names-that-honor-american-greatness/, accessed January 21, 2025.

[2] “At an election,” Lake Charles Echo, Lake Charles, LA, May 10, 1884.

[3] “History of Morgan City, La,” Morgan City: Right In the Middle of Everywhere, https://www.cityofmc.com/index.php/aboutmorgan-city/morgan-city-history.html, accessed October 7, 2024.

[4] “Big Shanty,” Georgia Historical Society, https://www.georgiahistory.com/ghmi_marker_updated/big-shanty/, accessed October 7, 2024.

[5] Neil P. Chatelain, Treasure and Empire in the Civil War: The Panamá Route, the West and the Campaigns to Control America’s Mineral Wealth (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2024), 13.

[6] For example, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and Carrollton Sun were both in print during the Civil War.

[7] Neil P. Chatelain, “USS Pittsburg or USS Pittsburgh?” Civil War Navy – The Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 1, Summer 2020, 63-64.

[8] James G. Hollandsworth Jr. The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 1995), 96.

Excellent article! For what it’s worth, the entire area is known as “America” or “The Americas,” because it’s comprised of North America, Central America and South America, so I think the name change is fine. After all, the name change is not “The Gulf of the United States of America.” Furthermore, the Gulf actually touches more territory of the United States of America than that of Mexico, making the name change even more appropriate. Furthermoremore, it is the United States of America that patrols and cares for the Gulf; Mexico does nothing but use it for smuggling illegal aliens, drugs and contraband, making the name change even more appropriate. Who knows, it might even become El Golfo de Trump, or Mar-A-Lago-A-Golfo. Rolls off the tongue!

Interesting question as Golfo de Mexico seems long established, though “Mexico” is probably best considered as co-extensive with the Aztec Empire, later Kingdom of Mexico with not that much coastline on the Gulf, compared to Provincias Internas de Oriente.

Yup. And they couldn’t fit “Gulf of Montezuma” on the map. Not enough room.

Unusual topic but neat & informative post. Here’s my contribution on the name change subject.

One of the more unfortunate names ever given a military organization was the “Invalid Corps,” a force consisting of U.S. troops disabled to varying degrees but who still could be useful (e.g., guards, rear echelons roles). Adding to the denigrating designation, at the time the same initials “I.C.” were stamped on condemned property to signify “Inspected-Condemned.” In what must have been a belated realization of the effect on morale of the original title, the corps’ name was subsequently changed to “Veteran Reserve Corps.”

Istanbul was once Constantinople. In 1868 Edo, Japan became Tokyo, Japan.

I read recently Thompson Creek that runs by Port Hudson, Louisiana was originally settled by a small group of Acadians in the late 18th century for a few years and was called Bayou des Écores.

I’d like to rename Shreveport to Caddo City.

I second the motion to make Shreveport now Caddo City, and call for a vote.

Heck, I want to get rid of all the old English names still clinging to our land. New York, New Jersey, New Hampshire, King’s County (Brooklyn), Queen’s County, Camden, Prince William County, Maryland, Georgia, etc. – I’m amazed these names were kept following the Revolution. I adore our Indian place names – do you know any words better than “Mississippi” or “Shenandoah”? – and the inclusion of thousands of Indian names from various nations in our lexicon has led me to declare that we do not speak English anymore, we speak American, because these names are not in the dictionary of the United Kingdom and the other English-speaking peoples. I need a second, please, gentlemen!

Gulf of the Americas. Now, is EVERYONE happy?

The ‘s’ is often a fine solution for a variety of issues…except for people with a lisp.