Research for a Novel Upended a Family Civil War Legend

ECW welcomes guest author Glynn Young.

The story had been handed down for four generations. My great-grandfather Samuel, too young to enlist as a soldier in the Civil War, had instead served as a messenger boy. At war’s end, he’d been surrendered with the final capitulations in the East (whether part of Robert E. Lee’s army or Joseph Johnston’s wasn’t specified). He’d made his way home to Brookhaven, Mississippi, mostly on foot. When he arrived, he discovered the family had fled to Texas, so his journey continued, again mostly on foot, until he found them. They eventually returned to Mississippi.

My father would speak in solemn tones whenever he told the story. He said the family hadn’t owned any slaves. “We come from a family of shopkeepers,” he’d often say. “It’s in the census records, and no slaves are listed with the family.”

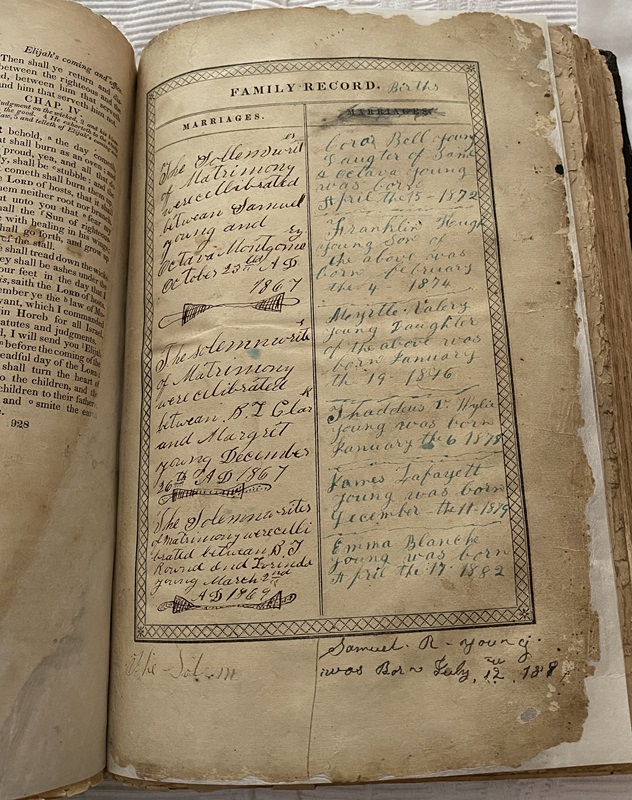

The family Bible, with its records of births and deaths, offered some supporting evidence. Samuel’s two older brothers had both died during the war. Samuel himself was 13 or 14 when the war began. His birth entry is unclear; it could be 1845 or 1846, and his tombstone reads 1845. An entry for a Jarvis Seale simply noted the date of his death, April 6, 1862; my father guessed he was perhaps a cousin or a close family friend. Much later I’d learn that he was Samuel’s brother-in-law who died during the battle of Shiloh; he’s the only non-blood relative listed in eight pages of records.

I dutifully passed the story down to my own two sons, who were both struck by the idea of having an ancestor involved in the Civil War.

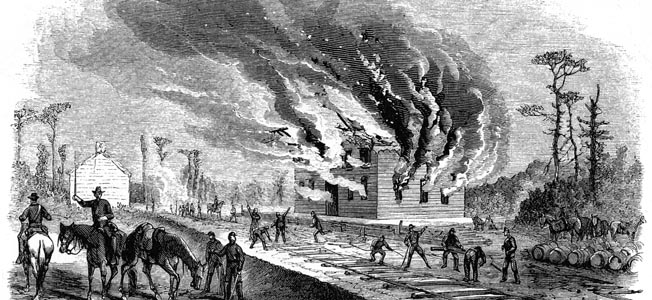

The family story lay there in memory, until I thought it might make an interesting novel. A young boy, caught up in the drama of war, making his way home through the wreckage of the Confederacy, walking from Virginia or North Carolina all the way to southern Mississippi and then on to Texas. An added aspect concerned the town of Brookhaven itself; it had been on the path of Grierson’s Raid in April 1863, and the family lived in the area.

I started with the family Bible. The records of marriages, births, and deaths were written in the same hand, presumably my great-grandfather’s. The conservator who had preserved the Bible, bound together by twine when my father gave it to me, said it had been printed about 1870. He also said that tens of thousands had been sold door-to-door after the Civil War; families bought them specifically to preserve the memory of those who had died.

My great-grandfather’s entry was simple: “Samuel Young, son of Franklin and Margaret Young, was born January 22nd, 1845” (or 1846). And it presented the first problem with the family legend. Samuel would have been 16 at the start of the war, old enough to enlist although a parent’s permission was required until age 18, which he became in 1863.

Then I read about messenger boys in the Civil War. Yes, young boys did run messages for army commanders. But given Samuel’s age, he would have more likely been a soldier.

Then, through contacts with other branches of the extended family, I learned of a counter-legend about Samuel, one radically different. The story was that Samuel was kept at home by his father, because of the two older brothers serving. At one point, his father paid a substitute $300 and a horse saddle to take Samuel’s place in the draft. My great-grandfather did deliver telegrams for the telegraph office, but it was regular deliveries.

By 1864, the family had no choice; Samuel had to enlist. But instead of being sent to the Eastern Theater, he was sent to Texas where, he said, he didn’t fight a single Yankee, but “chased a lot of Injuns.”

One other disruption to my family legend was included in that alternative account. Samuel reportedly told his grandchildren that he was born on the family plantation in Johnston Station (several miles south of Brookhaven), the family had 17 slaves, and the war cost the family everything.

I checked the 1850 and 1860 census records. And there it was! Franklin’s father and two older brothers were all identified as farmers. And the top of the record page explained the lack of names of slaves; it was a census record of “Free Citizens of Pike County.” Samuel is listed as seven years old in 1850 and 15 in 1860. I suspect the 1850 census taker erred; the 1860 listing matches the family Bible record.

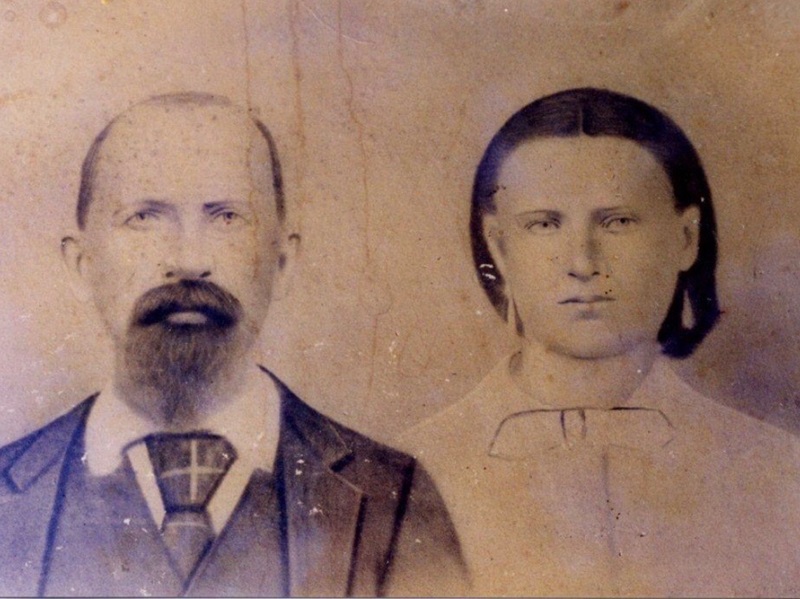

After the war, Samuel continued farming. He married Octavia Montgomery in 1867; they had seven surviving children, including my grandfather James. She died in 1887; my great-grandfather never remarried. Kept in the family Bible was a lock of deep auburn hair that I suspect was my great-grandmother’s. Samuel lived in the Brookhaven area until he retired from farming and joined the household of one of his daughters in Louisiana. He died in 1920 and was buried in a small cemetery outside Alexandria, Louisiana.

I was deep into the writing of the historical novel when I came across the alternative family legend. I sensed the alternative had more truth to it than the one I’d received from my father. I could understand the desperation of a father with two dead sons doing everything possible to keep the remaining son out of the war.

By this time, I’d read everything from The Real Horse Soldiers: Benjamin Grierson’s Epic 1863 Raid Through Mississippi, by Timothy B. Smith, Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era by Frances Clarke and Rebecca Jo Plant, and Chris Mackowski’s The Battle of Jackson, Mississippi, May 14, 1863 to histories of Mississippi during the war and Reconstruction, general accounts of the war, collections of letters, and soldiers’ memoirs. (The published novel has eight pages of bibliography.) I was so deep into research and writing that, for my novel, I stayed with the family legend as I originally heard it.

The research taught me one major lesson: memory can be a frail, funny thing. What’s passed down in families may be true, have elements of truth, or be completely made up. Historians know this and must sift, document, correct, and revise. Historical novelists also need a similar determined doggedness.

But I still wonder how that family story arose in the first place.

————

Glynn Young is the author of five contemporary novels, the non-fiction book Poetry at Work, and the historical novel Brookhaven, published in December 2024 by T.S. Poetry Press. A retired speechwriter and corporate communications director, he lives with his family in suburban St. Louis, MO.

My Civil War ancestor story (captured at Gettysburg survived Andersonville) may be of interest. See hiramshonor.blogspot.com.

I’ve read several books about Andersonville and some of the Northern prisons as well.

Thank you for this story. I have a great grandfather who served for the North. What I know is not as dramatic and there are many gaps that census records don’t answer. And no one in the family would talk about him. I can only speculate. Congratulations for unearthing your family’s true story.

Thank you, Josephine!

The maternal Cajun side of my family has a family legend of at least one ancestor walking back home after the war. Regrettably, I have not researched this to find out if remotely true. If this did happen, the guy probably “only” walked from north Louisiana to south Louisiana, but who knows.

The one Cajun ancestor’s Civil War existence I do know about is my mother’s grandfather who was born in 1849 in Grand Coteau, Louisiana. He sired my grandfather in 1911. My mother came in 1939 and me in 1977.

Lyle, we share some Cajun heritage. My maternal grandfather was from Reserve; he married a woman who was second-generation American and whose grandparents emigrated to New Orleans from Alsace-Lorraine (there were German as opposed to French). My father’s family came from southern Mississippi; he was born in Jena (near Alexandria) and spent most of his youth in Shreveport. My wife is from Shreveport; every time we visit she points out the site of Fort Humbug, the fake fort placed on the Red River bluffs to dissuade Gen. Banks from going any closer to Shreveport. And her father’s family lived mostly in Mansfield, site of the Civil War battle. We’ve got Civil War heritage all over us.

It’s a small world, Glynn! I am familiar with Reserve. The town renamed to Reserve from Bonnet Carre by Leon Godchaux, a Jewish-French-Alsatian immigrant. The once popular and prominent Louisiana department store Godchaux’s is named after him, as you probably know.

I grew up not far from Brookhaven, MS but have only driven past it on the interstate. I know where Jena is, but have never been. I knew an LSU classmate from there. I do have some Cajun/Creole relatives in Alexandria though… including some Beauregard cousins.

Several paternal ancestors may have participated in the Red River campaign and may have been at Mansfield. I only know they were paroled in Shreveport at the end of the war.

Thank you sharing and writing such an interesting article. You made a great point on how stories regarding family members are passed down. Like you said some stories are true, some have some true parts and others are great works of fiction. I enjoyed your article. Thanks again. Bobbie

are there other pages of family data in the family bible?