Rolling on the River: Down the Mississippi to Memphis

Following Union victory at Shiloh in April 1862, Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard withdrew south and dug in at Corinth, Mississippi while Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck’s three armies began a glacial advance on that vital railroad hub. Meanwhile, the Union Western Gunboat Flotilla proceeded in parallel down the Mississippi from its victory at Island No. 10 toward Memphis, Tennessee, less than 100 miles to the west of Corinth. Vastly outnumbered, beset by typhoid and dysentery, Beauregard abandoned Corinth on May 29 while ordering the evacuation of Memphis and forts defending that river city.

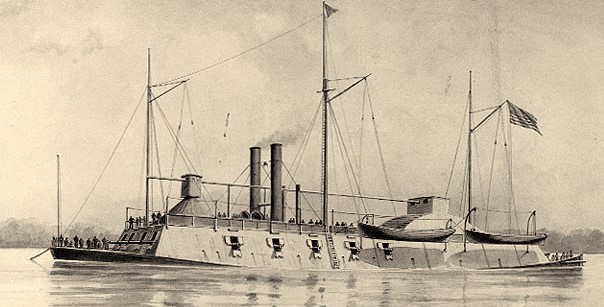

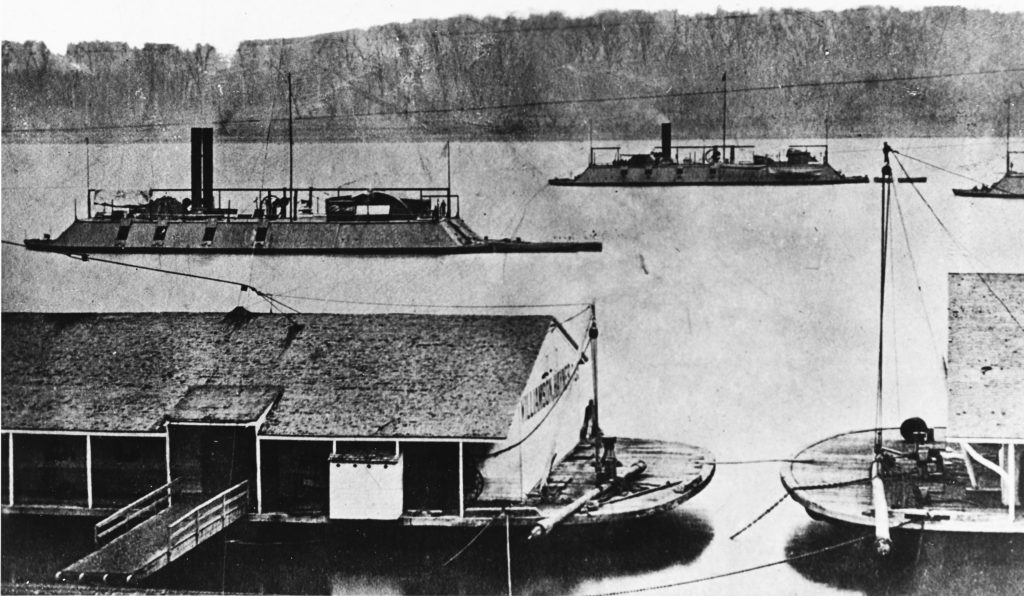

The Union flotilla occupied an empty Fort Pillow and began its descent on Memphis—76 miles downriver—at 12:45 p.m., June 5, 1862. The river ironclad USS Benton was flagboat carrying Flag Officer Charles H. Davis commanding the flotilla. Also aboard was the special correspondent for the Cincinnati Daily Commercial. Identified only by the initials C. D. M., he reported the entire passage in the newspaper’s June 11 edition beginning with: “Here we obtained a fine view of the entire fleet.”

Benton “led off handsomely” followed by tugs Jessie Benton, Terror, and Spitfire. Next came at a respectful distance the ironclads St. Louis, Louisville, Carondelet, Cairo, and Mound City, trailed by ordnance steamers Great Western and Judge Torrence, and supply steamer J. H. Dickey. “Old Sol blazes out in all his glory, fast dispelling the dark murky clouds that betokened rain during the morning.”

They passed Hatchie Landing with eight houses and a warehouse, three probably deserted, and then the town of Fulton, “which, like nearly all the small towns on landings along the Mississippi, presents an antiquated appearance,” and the Lanier farm. “The huge black gunboats, followed by the tugs, in grand array, dance gracefully through the water, while their quick and loud escapement of steam, furnishes music for the grand occasion. . . . Here, one gunboat passes another, giving all the life and interest of a Mississippi steamboat race.” (The reader might question the image of ironclads dancing gracefully.)

The correspondent’s term “steam escapement” refers to the sharp, high-pitched hissing or whistling noise intermittently produced as a boiler’s safety valves lift to release steam, relieve overpressure, and prevent explosion. This iconic sound was accompanied by the steady “chug-chug” of pistons and the periodic high-pitched wail of the whistle. The era’s steam engines were huffing, puffing, hissing, clanking, slick and oily, clamorous monsters with fast gears, shafts, and rods surrounded by scalding-hot water and steam pipes, not to mention intense boiler fires. This cacophony—more commonly associated with steam locomotives—emanated from the entire flotilla and transmitted distinctly across the water, although somewhat attenuated by iron bulwarks.

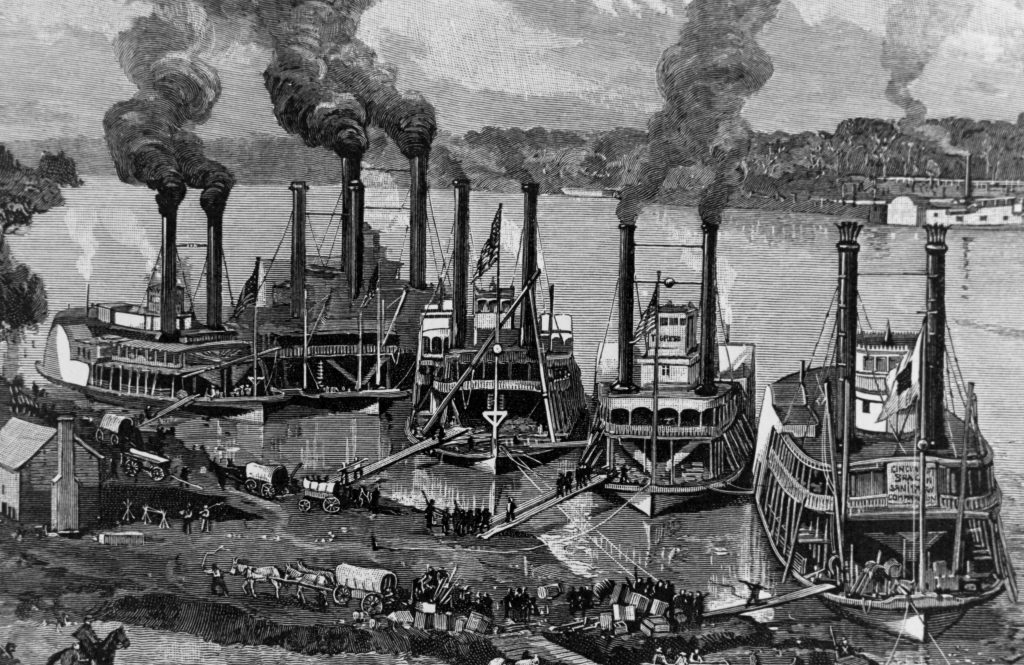

“The spectacle is grand and imposing,” continued C. D. M. “The star-spangled banner floats gracefully and free to the breeze, from each craft. In the distance, with the aid of the glass [spyglass, telescope] . . . is seen the [troop] transports with Col. Fitch’s command, steaming along in order, their white steam and white paint, contrasting widely with the black coal clouds of smoke, pouring out voluminously from the chimneys of the dark ‘iron-clads.’” At the tail end of this 10-mile procession came mortar boats towed by auxiliary steamers.

By 2:00 p.m., the flotilla saw Widow Craighead’s place, “which appears to have suffered materially.” Large quantities of cotton, loose and in bales, floated downriver. Coming in sight of Fort Randolph, they observed four deserted batteries along the bluff and below the ramparts with the “old flag,” i.e., Stars and Stripes, waving from a warehouse. “During all this time, [Flag Officer] Davis, with a quick, almost impatient step, quietly paces the quarterdeck.”

Shawl’s plantation, at the foot of Chickasaw Bluffs, was deserted, “the only smoke visible being from the chimneys of one of the negro houses. Here, and all along the river, we find loose cotton abundant, having been washed in to the shores.” They had steamed twelve miles with no signs of the enemy. “We hear they are only one hour ahead with their fleet of gunboats, and are stopping at all the plantations, and burning cotton. The smoke of bales in flames proves our information correct.”

Islands 35 and 36 floated by. The river split around islands forming the main channel down one side and a smaller, often more rapid “chute” on the other. The larger Benton kept to the main while one or two ironclads took the chute. “They occupy both channels in order to open the Mississippi effectually, and teach the rebel gunboats the art of naval warfare.”

At 3:30 p.m.: “We pass Pecan Point. Here we find more cotton floating by the bale, and both negroes and whites busily engaged in gathering it up as fast as the current drifts it ashore. It is picked up in skiffs, and packed off by horses, wagons and men. At almost every plantation the advance of our flotilla is greeted by the waving of hats, bonnets and handkerchiefs, by both sexes, as well as the masters and slaves.”

A large sidewheel steamer named Sovereign appeared above Island 37, bound upriver. Davis ordered a warning shot as a signal to heave to for inspection, but she rounded down and fled, so the ironclads opened fire. Benton let go nine rounds, Carondelet eight, and Cairo four; all fell short, went over, or scattered around. Benton’s Lieutenant Joshua Bishop took a 12-pound Dahlgren howitzer and 16 gunners aboard the tug Spitfire—“a little, wee craft” 75 feet long—and took off in pursuit. “The race is exciting, of course,” enthused C. D. M. Both vessels disappeared around the bend. “Here the smoke of burning cotton is plainly visible on the left hand shore.”

Just then, two men hailed from the right bank and were brought aboard Benton by the tug Terror. Pilots Sam Williamson of the ironclad Louisville and John Tennyson of her sister ship Pittsburg had been sent downriver in a dugout canoe by Davis with dispatches for Flag Officer David G. Farragut’s squadron, then ascending from New Orleans. The two pilots were compelled to evade Rebel gunboats by dodging into the willows and cottonwoods along the shore, and had observed Sovereign burning all the cotton she could find. “[They] were badly used by the mosquitos during the night previous, having slept in the woods.”

Benton descended the Tennessee side of Island 37 while Louisville and Cairo took the Arkansas chute. As the flagboat rounded the island at 4:40 p.m., Spitfire came into view nosed up to the bank alongside an apparently abandoned Sovereign. The big steamboat was faster, but the little tug had taken shortcuts through shallow bayous, caught up, and discharged a few shots from the howitzer. Sovereign’s captain beached her, jumped ashore with his crewmen, and “made tracks for the tall timber,” but not before stoking the boilers and placing weights to hold down the safety valves.

When Lieutenant Bishop and his men boarded, they found only a sixteen-year-old lad named E. A. Honness, formerly of Cincinnati, who had had been pressed into Confederate service. Assisted by “a negro,” he had removed the weights from the valves, opened the fire doors and flu caps, and was pouring water on the fires, saving the vessel and Union sailors from a catastrophic explosion.

One of Sovereign’s pilots, a local named Lewis, also surrendered. He and Honness said they were unaware the Federal fleet had started downriver, and that Sovereign was proceeding to Forts Pillow and Randolph to convey Confederate troops to Memphis. As soon as the captain sighted the ironclads, he intended to surrender but “his heart failed as he approached.” The boat had been badly used transporting troops and was much out of repair. She had collided with the Rebel ram General Beauregard the night before crushing a section of the bow.

However, continued C. D. M., “She is capacious and roomy, and will make a first rate naval hospital or supply steamer. . . . Her cargo only consisted of six bales of rope and cotton. The capture of this large steamer by so diminutive a ‘tug,’ is a new era in gunboat warfare.” A Benton junior officer went over to take Sovereign north as the flotilla continued downriver. “We are also hailed by men, women and children on Island No. 37, their camp indicating they are refugees. We did not stop, however, our mission being of too much importance to relieve them.”

“We glide along smoothly, until 8 20 P. M., when we pass Fort Harris, only six miles above Memphis. The night is clear and mild, and pale Cynthia[*] beams out in all her glory. All eyes and glasses are closely observing both shores, in the vicinity of ‘Paddy’s Hen and Chickens’—a cluster of islands—and on the look out for the first glimpse of Memphis.” Nighttime navigation was particularly treacherous.

Finally, numerous twinkling lights were sighted along the bluff, “together with the fires of an ascending steamer, perhaps a rebel gunboat.” At the captain’s order, “Pilot Duffy gives her the wheel, bringing the huge chief of the ‘iron clads’ around most beautifully.” Benton swung her bow upstream and dropped anchor a mile and a half above the city. Flag Officer Davis conveyed instructions to the messenger tugs; they “dart and whiz off steam” passing word to the flotilla.

The other ironclads anchored nearby while the caravan of commissary boats, ordnance boats, troop transports, towboats, and mortar boats tied up along the Arkansas shore and threw out a heavy body of pickets. “In the meantime, the men sleep by their guns, while the ‘boarding pikes’ are brought on deck, and the usual precautions taken to be ready for a surprise or a night attack…. Being weary and jaded noting the many interesting events of the day…, we go to bed, anticipating still more lively and vivid scenes on the approaching morrow.” Dawn, June 6, 1862, would break on the naval battle of Memphis.

Extract from the forthcoming book: The Naval Campaign for Memphis, April 12-June 6, 1862.

[*] Cynthia is a poetic and mythological name for the moon derived from Mount Cynthus on the island of Delos where the Greek goddess Artemis was born.

God, what a florid, windy gasbag that newspaperman was! The Edward Everett of the Mississippi River.

Thank you for bringing this to light and great photos, too. “[They] were badly used by the mosquitos during the night previous, having slept in the woods.” If only we had a further mention of their health after being the buffet. Thank you CDM for this adventurous travelogue, worth learning to read just for this. The loose bales of cotton along the river – today we watch Customs and Border Patrol television shows, and once in a while they highlight an abandoned package of cocaine wash up on the Florida shore, a possible modern parallel.

My oldest sister has the diary of John Tennyson, Mississippi Union Scout. I have read it years ago, but she is embarrassed by his staunch Christianity and constant references to God. She will not let anyone else read it, or even share with direct cousins. Perhaps, with the correct approach (appealing to her perceived intellect) She would not give me a copy years ago. I had to mail it back. It was a fascinating and captivating read for me. It is true American History. She must be convinced to share it as she is currently 77 years old and somewhat debilitated.