Was the Battle of Hatcher’s Run Inconsequential?

ECW welcomes back guest author Nigel Lambert.

During the freezing night of Tuesday, February 7, after three days of bitter fighting, the guns fell silent along Hatcher’s Run. The Union’s Eighth Petersburg Offensive (or battle of Hatcher’s Run) involved over 43,000 Union troops and around 15,000 Confederates. Total casualties stretched to over 2,500. Fourteen Union soldiers would receive Medals of Honor. And yet, it’s fair to say that posterity has not treated the battle too kindly.[1] I often hear that such neglect is because nothing of consequence (or significance) resulted from the offensive. I now explore this opinion.

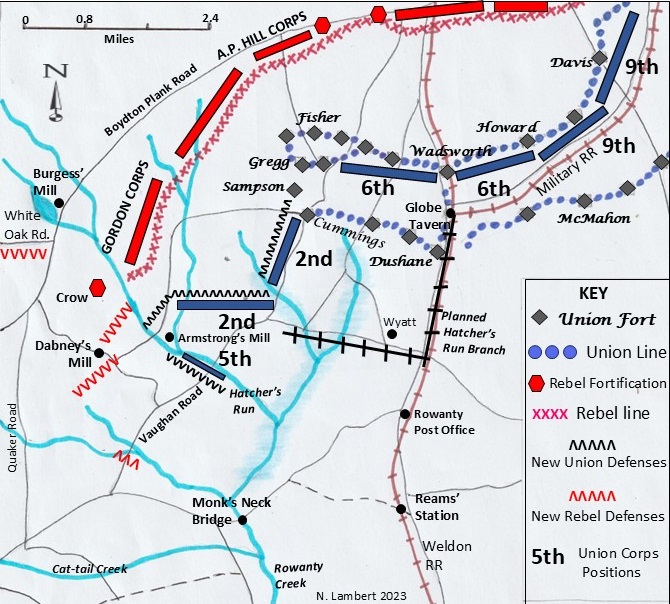

As his troops disengaged from the fighting, Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade issued a three-point circular defining new works and troop dispositions in light of the battle:

- The chief engineer would oversee the construction of “an entrenched line from Fort Sampson [the western end of the Union line] to Armstrong’s Mill.” The line would involve extensive breastworks and selected artillery positions. Works would also be constructed at Armstong’s Mill and the Vaughan Road crossing of Hatcher’s Run, with dams “built on Hatcher’s Run, and the stream obstructed as much as possible.”[2]

- Once constructed, “the extended line will be held as follows: The IX Corps, from the Appomattox River to Fort Howard; the VI Corps, from Fort Howard to Fort Gregg; and the II Corps, from Fort Gregg to Armstrong’s Mill.” The V Corps would hold the Vaughan Road crossing and picket Hatcher’s Run above and below the crossing and along “Vaughan Road via “Cummings’ to Wyatt’s.” It would protect the rear and support the II or VI Corps if attacked. The cavalry division will be posted on Jerusalem Plank Road and picket from the left of the V Corps to the James River.[3]

- “The chief quartermaster will extend the Military Railroad to conform to the new disposition of troops. The chief engineer and corps commanders will … construct corduroy roads to establish secure and prompt communications.”[4]

Federal forces began implementing these directives on February 8. In essence, the acquisition of the Hatcher’s Run crossings at Armstrong’s Mill and Vaughan Road enabled the Union to extend their left flank three miles west. Federal forces had captured these crossings before. The II Corps secured them during the Sixth Offensive (October 27, 1864), with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant visiting Armstrong’s Mill. That offensive failed, with Union forces returning to their original lines, relinquishing the two crossings. On December 9, Federal troops led by Bvt. Maj. Gen. Nelson A. Miles captured the two Hatcher’s Run crossings, only to withdraw the following day. Thus, the decision to hold the crossings following the Hatcher’s Run battle was significant.[5]

An essential part of the extension entailed connecting the new works to the railroad network. The Military Railroad was the Union’s main artery for transporting troops, materials, and supplies to the Petersburg front. It ran from City Point, the U.S. supply base on the James River, to Globe Tavern on the old Weldon Railroad. On Sunday, February 12, Chief Engineer James J. Moore and his assistant C. S. McAlpine arrived to survey the project. The most workable route for the “Hatcher’s Run Branch” involved extending the line from Warren Station (next to Globe Tavern) down the old track bed of the Weldon Railroad for two miles before bearing right to the Cumming’s house near Vaughan Road. Construction began the following day, and the railroad was effectively operational by the month’s end.[6]

Although not the mission’s original aim, extending the Union line westwards was how Union commanders “sold” the offensive to the Northern public and politicians. This was a more uplifting narrative than the initial aim, which involved an infantry-supported cavalry raid on what transpired to be a primarily abandoned Rebel supply line. In early 1865, Grant’s main fear was waking up and discovering that Lee’s army had slipped away, abandoning Petersburg. After six weeks of inaction, Grant’s Eighth Offensive certainly kept Lee occupied and allayed any such fears.[7]

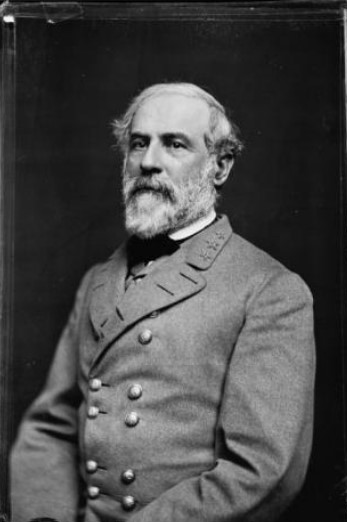

The battle also provoked significant responses from the Confederacy. It was during the battle (February 6) that Gen. Robert E. Lee officially became commander-in-chief of all Confederate forces. The day after the battle, Lee wrote to the newly appointed (also on February 6) Confederate Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge, describing the extreme plight of his soldiers. “Some of the men had been without meat for three days, and all were suffering from reduced rations and scant clothing, exposed to battle, cold, hail, and sleet.” Lee promised to send his chief commissary, Col. Robert G. Cole, to Richmond to see what improvements he could effect. Lee added, “If some change is not made and the commissary department reorganized, I apprehend dire results. The physical strength of the men, if their courage survives, must fail under this treatment.” He also mentioned that he had to disperse his cavalry for want of forage. When President Jefferson Davis heard the news, he replied, “This is too sad to be patiently considered, and cannot have occurred without criminal neglect or gross incapacity. Let supplies be had by purchase, or borrowing or other possible mode.” On February 16, Breckinridge removed the inept Lucius B. Northrop as commissary general and replaced him with Isaac M. St. John. Although supplies to Confederate troops improved, it was too late to change the war’s outcome.”[8]

Following the battle, the Confederates extended their Boydton Plank Road lines south beyond Hatcher’s Run, including the Dabney’s Mill site, to block any direct advance to the Southside Railroad. But with the Federals now controlling the main Hatcher’s Run crossings, they had many options for sweeping around Lee’s right flank. To frustrate these threats, Lee built a defensive line stretching several miles westwards along White Oak Road just south of Burgess’ Mill. However, considering his recent Hatcher’s Run experiences, Lee realized that Grant would eventually get beyond his right flank. By February 22, Lee had plotted a retreat west should they evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. He planned to rally his army around Burkeville (30 miles northwest of Petersburg), where the Southside Railroad joined the Danville Railroad. To this end, he moved his surplus materials to Amelia Court House, just north of Burkeville.[9]

At the start of 1865, desertion of Confederate soldiers around Petersburg became rife. Many interacting factors provoked the absconding: the lack of food and clothing during a harsh winter, the sense that defeat was inevitable, and the concern for families in the path of Sherman’s army marching through South Carolina. The hardships endured during the bloody battle of Hatcher’s Run certainly helped push demoralized soldiers toward deserting. Many Rebels openly surrendered to the Federals during the battle. As historian John Horn noted, “The floodgates [of deserters] opened after the battle of Hatcher’s Run.” Between February 9 and February 28, 1,148 Confederates surrendered to Union forces, a larger number than they lost at the battle. In addition to these recorded fugitives, many other Rebels simply deserted and returned home.[10]

Just three days after the battle, President Davis adopted a proposal from Lee for a 30-day amnesty for any deserters who returned to their regiments. To address the stream of Tar Heel soldiers back to North Carolina, toward the end of February, Lee sent valuable troops from his already stretched front line to the state border to round up deserters.[11]

Thus, the battle provoked substantial direct and indirect military consequences. The resulting Union line extension was the last of the Petersburg campaign. It meant that Lee had more miles of front to protect with his dwindling army. Not only had he lost valuable officers[12] and men during the battle, but in the following three weeks, an even greater number of his soldiers deserted. Finally, the new Union lines provided an effective launchpad for the Appomattox Campaign (March 29 – April 9, 1865) that eventually turned the Confederate right, forced the evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond, and the surrender of Lee’s army.

Given the scale and drama of the Hatcher’s Run battle and the significant outcomes outlined above, it’s hard to comprehend why posterity largely overlooked the event. As renowned historian Freeman Cleaves noted, “This battle … finds no conspicuous place in the chronicles of the war.”[13]

Dr. Nigel Lambert is a retired British academic who lives near Norwich, England. He has published many bioscience and social science articles linked to various medical issues. A life-long Civil War enthusiast, he recently became interested in the battle of Hatcher’s Run. Surprised by the sparse and conflicting literature on the battle, he employed his scientific and qualitative research know-how to advance our understanding of the battle. Working with US experts on the Petersburg campaign, he has created an extensive e-library for the battle.

Endnotes:

[1] Douglas S. Freeman, Bruce Catton, and James M. McPherson all ignored the battle in their respective seminal books: Lee’s Lieutenants (1944), A Stillness at Appomattox (1953), and Battle Cry of Freedom (1989).

[2] The full text of Meade’s circular can be found at The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 46, Part 2, 450.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Hampton Newsome, Richmond Must Fall (Kent, OH, 2012); OR 42/1: 263-64, 267-68, 272-76; OR 42/3: 890-91, 898, 900-902.

[6] Mike Willegal, Building a Railroad, *hatchers run book-II (willegal.net), 2022, 1-37.

[7] Nigel Lambert, “When Grant Just Wanted to Do Something” Emerging Civil War, 2024,.

[8] OR 46/1:382.

[9] Armistead L. Long, Memoirs of Robert E. Lee: His Military and Personal History (New York, 1886), 404. Earl J. Hess, In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications and Confederate Defeat (Chapel Hill, NC, 2013), 234, 246; Chris M. Calkins, The Appomattox Campaign (New York, 1997), 10-11.

[10] Noah A. Trudeau, The Last Citadel (Baton Rouge, LA, 1991), 294-95; John Horn, The Petersburg Campaign (Cambridge, MA, 1993), 217-18.

[11] Lee W. Sherrill, The 21st North Carolina (Jefferson, NC, 2014), 417; Vines E. Turner & H. Clay Wall, “The 23rd Regiment,” in Walter Clark, ed., Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, in the Great War 1861-65. 5 vols. (Goldsboro, NC, 1901), 2:262-63.

[12] Lee lost a division commander (John Pegram) killed, and two brigade commanders (G. Moxley Sorrel and John S. Hoffman) seriously wounded.

[13] Freeman Cleaves, Meade of Gettysburg (Norman, OK, 1960), 306.

Well done! Hopefully, Wil Greene will give this battle its due in his Petersburg trilogy (volume 2 out this spring).

Thank you for your warm comments. I have been discussing the battle with Will Greene recently, I’m sure he’ll do an excellent job. His first volume is a tour de force.

Great article! Thanks for highlighting this battle. I would like to hear more about the fourteen Medals of Honor. Your map was wonderful.

Thank you for your comments, much appreciated. I wrote a blog on the 14 MoH guys last year

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2024/06/25/fourteen-union-heroes-from-a-forgotten-battle/

Each is a fascinating story. I’m trying to get a marker sited on the battlefield to remember them, as currently their deeds are not acknowledged. 160 anniversary of the battle ending today, so a very timely post. I have been marking each day on civilwartalk on their Petersburg forum. Plus I recently did a podcast about the battle for the anniversary.

https://darrenscivilwarpag8.wixsite.com/acwandukhistory/post/the-battle-of-hatcher-s-run-with-nigel-lambert

Thanks so much. I don’t know how I missed that blog. I am always interested in Medal of Honor recipients. Looking forward to more articles by you.

Cheers

Very interesting. Thank you for sharing your insights.

Algorithm: If the battle has been discussed on ECW, it was not inconsequential.

You actually make a very interesting point Eric. You’ll be surprised how many times I’ve been told the battle was inconsequential. Posterity has not treated the battle too kindly. This is actually what got me interested in Grant’s 8th Petersburg Offensive initially, long before I knew the dramatic, roller coaster story of the battle itself. I usually end any presentation I give on the battle with a list of seminal books that chose to ignore the three bloody days: these include Grant’s memoirs, Gordon’s memoirs, Battles & Leaders (one line in a large footnote to be fair!), Douglas S Freeman’s Lee’s Lieutenants, Catton’s Stillness at Appomattox and McPherson’s Battle Cry to name three Pulitzer Prize Civil War titans. Just to name a few!

Until I revamped the Wiki page last November, it was a derisory 2 pages, I can point to engagements 10 times smaller in scale than Hatcher’s Run that have a comprehensive wiki page. On the major Civil War forum CivilWarTalk, the battle doesn’t even feature on it’s calendar of events!

I’m planning a couple of articles on this bizarre aspect of the battle.

“Out of sight out of mind” – visibility is crucial in remembering history, and I thank ECW for supporting my work on an unpopular battle, and helping to raise awareness.

Thank you for your wonderful note, Nigel. It’s not just obsessiveness from Civil War nutcases – it’s important. This battle is important, and this forum is, as you state, important for raising awareness on a number of battles, events and personages. I personally have benefitted from both the great interest in the Western Theatre that so many historians have – never enough material out there on this, and I’ve learned so much in their pieces – and from people whose favorite topic is river and ocean-going vessels used in the war, as information about one of them is important to the book I am writing. Besides general sources, I didn’t have the slightest idea where to search, but several people in this forum stepped up and supplied me with voluminous information without even being asked.

The other reason your work on Hatcher’s Run is important is because I have found in writing my book that we discover new things by going over and over the same ground, and what we glean can be vital to this particular battle, or to the campaign or the war on a larger scale. To be specific, I believe the Seven Days Battles are generally given short shrift. They’re lumped together and not seen as being as important as the battles in 1863. But my book largely centers around events in these battles. But in doing endless deep dives on everything connected with them in a search for what happened to a few individuals that week, I uncovered documents and then archaeological evidence that will rewrite how the history of one of those battles is written.

I’m certain the same has happened to historians in the past and will happen in the future – that is why this work is so vital.

Historian Nigel Lambert has made a compelling, well-researched case for the significance of the battle of Hatchers Run (Feb. 5-7, 1865).

Thanks John, glad you liked it.

It’s hard to view anything as “inconsequential” when it comes to the actions around Petersburg, especially for the Confederates. The attrition the Confederates suffered from sickness, battle, and desertions ensured that most if not all casualties were never ‘inconsequential’. Couple that with their government’s inability to supply Lee’s army, despite that army being so near the “breadbasket” that was the Shenandoah Valley and other sources, that had to inflict a mentality of inevitability as far as the Confederates chances to hold Richmond and to effectively continue to prosecute the war. This battle held Lee in place and set him up for what would be the final battles that drove him to Appomattox. That’s not “inconsequential” at all.

Thank you for a very good and informative article!

Thank you Douglas, I think that your words succinctly describe the situation perfectly. I may “steal” them when I’m next challenged on the battle’s relevance, and I need a snappy response.