A Medley of Death on the Yorktown Line

ECW welcomes back guest author Owen Lanier.

At first glance, the stories of Joe Durkee, Michael McDermott, and James Frampton don’t appear connected. They are three snapshots into intensely personal moments but, taken together, they paint a larger picture of the realities of a Civil War siege. Modern memory of Yorktown’s 1862 siege is that of a slow, procrastinating, delaying action. Unfortunately for the men along the siege works, this month-long siege was anything but. Today, let us look at the stories of men in a quiet siege.

A Child Dies: James Frampton:

Around 6:00 a.m. on April 22, 1862, Dr. A. P. Reichold of the 105th Pennsylvania heard a knock at his cabin door behind modern-day York High School, then a steam mill and III Corps headquarters. When the door swung open, a young 16-year-old stumbled through the door. James Frampton of Indiana County, Pennsylvania, did not have long to live. The previous night, unexpected snows caught the regiment’s pickets in the woods. Frampton and his comrades were unprepared for the rapidly changing temperatures.

The next day, James did not stop shaking. By morning, his comrades knew that typhoid had set in. Upon falling into Dr. Reichold’s arms, the young man ingested two shots of brandy. Although he did not stop shaking with fever, he lay down peacefully on the floor. A little under an hour later, James D. Frampton, a boy, died in Yorktown.

So, how do we know about James D. Frampton’s story? Luckily, newspapermen who followed the Army recorded their daily activities in their diaries. While the author of this diary changed Frampton’s name to Trampton, comparing the stories with lists of men who died on April 22 reveal only one match.

Upon finding James D. Frampton, who passed on April 22, the next step is finding out if he was indeed a boy of sixteen. This research revealed his actual age. Looking into census data confirms the tragedy. In the 1850 census, Frampton is listed as two years younger than his six-year-old brother. While his age is missing in the 1860 census, math assures us that Frampton was fifteen when the war broke out in 1861.

The stories of these men remind us that the 1862 Siege of Yorktown was not a quiet moment in war, but nearly thirty days of terror and loss. For weeks, more than 100,000 men sat along a twelve-mile front locked in a back and forth that foreshadowed the sieges yet to come. Men experienced constant sniper fire and the fear that their friend could die in an instant for no other reason than standing up. Artillery thundered around the clock while men scratched out sleeping holes in water-logged trenches. When Confederate iron and lead couldn’t reach them, the swamps and diseases could. Walking down a road without checking it for underground bombs could cost one a leg or a life.

Night fighting with Joe Durkee

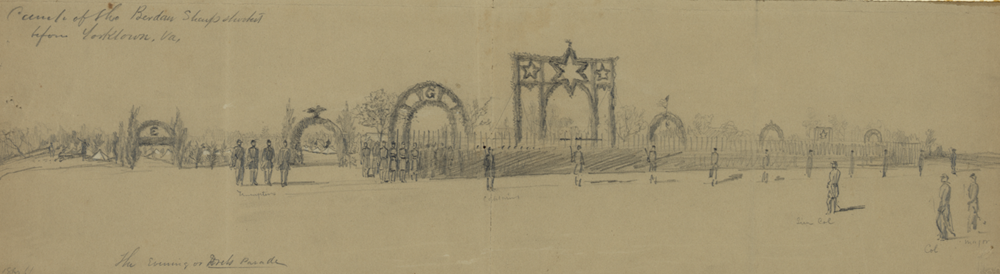

On May 1, around 11:00 p.m., Company G of the 1st United States Sharpshooters left its camp behind Wormley Creek and advanced to the siege lines. For the past two weeks, several companies of sharpshooters had been detached and sent up and down McClellan’s siege lines. Their primary job was protecting work details feverishly throwing up dirt for the big guns to come.

It was a moonless night. Lieutenant Frank Marble gestured for his detail of five men to move into the dark fields near what is today Yorktown National Cemetery. As the men came upon a knoll, they reckoned themselves 150 yards or more from the Confederate entrenchments. As Sgt. Maj. William Horton took stock of his unit’s position, Pvt. Joseph Durkee volunteered to provide an advanced vidette. Up the slight slope he went. Getting on his feet proved difficult. The sharpshooter slowly rose from the ground to creep forward. As he crested the ridge, a single shot rang out.

Sergeant Joel Parker glanced up to see Joe Durkee collapse to the ground. Gunfire erupted from the trees as the small band of snipers ran for their lives. Unfortunately for the small detail, they had mistakenly crawled within 40 yards of the Confederate lines.

Three days later, Company G returned to where they had last seen their comrade. They did not have much time. Divisions of men marching for Williamsburg passed by as the body of Durkee was found. His rifle and shoes were gone. If the regimental historian is to be believed, all that remained was a note stuck to his body thanking the sharpshooters for a donation of liquor.

The men buried Durkee’s body and struck out for Williamsburg. Later that day, the 5th North Carolina charged upon Hancock’s brigade on the left of the rebel line during the battle of Williamsburg. A sought-after trophy lay on the field after the action: Joe Durkee’s Colt rifle. Legend has it that the gun was returned to Col. Hiram Berdan, commanding the 1st United States Sharpshooters.

Today, Durkee lies in an unmarked grave, whether still on the battlefield or somewhere in the National Cemetery–no one knows. For us, Joe Durkee is but one life in a national story, but for his family, his death and unknown grave was their Civil War.

Tread Softly with Michael McDermott

“I have strange and startling news to tell you. Yorktown is in our hands. Evacuated earlier this morning,” wrote Frank Lemont to his mother.[1] As the news spread down the siege lines, Michael McDermott and the men of the 40th New York Infantry scaled the parapet of the White Redoubt–just outside of town. Immediately after, his comrades heard an explosion and watched McDermott’s body tumble into the works; Michael had just become the first casualty of mine warfare in America.

Terror awaited in the town. On May 4, 1862, news reached Union lines that the Confederate Army had abandoned Yorktown. Before the sun rose, columns of Union men began pursuing the retreating Confederates towards Williamsburg, many of them passing through the sallyport of the nearby entrenchments. Signal corpsmen also started arriving at the gate to lay telegraph cables and prepare the siege train for shipment via the town’s sprawling wharves.

Mr. D.B. Lathrop, a telegraph operator on Brig. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman’s staff, also entered the sallyport. As he approached the former Confederate telegraph office, he noticed cut wires dangling out front. Upon reaching out to examine the broken communications, his boot brushed a tripwire, setting off an improvised explosive device. The stretcher bearing a disfigured Lathrop passed back through this gate; he died the next day. Charles Bacon of the 15th New York engineers remembered, “That telegraph operator Lathrop was killed close by me. I was talking with him a moment before and had been walking all around the spot. I left Yorktown shortly after I saw the operation of that shell.”[2]

Immediately, all Union soldiers were ordered clear of town. Additionally, the marching columns were rerouted to cross between the Red and White redoubts and around town to the Williamsburg-Yorktown road. Confederate Brig. Gen. Gabriel Rains, the architect of the landmines, planned his trap solely in town. It was a success. While the mines killed relatively few, they slowed the Union’s pursuit.

To deal with the threat of landmines in Yorktown, George McClellan intended to use Confederate prisoners to clear the streets. When these prisoners failed to remove the mines, likely because they had placed them and planned on watching them explode among Union ranks, McClellan resorted to driving the Army’s beef cattle down the streets. This worked well enough for government work. By day’s end, Yorktown was occupied. Scores of men lay dead and wounded thanks to these “infernal contraptions.” This gate and others like it were likely the last entrance these men walked through before their deaths.

Owen Lanier is a senior at Gettysburg College. He coordinates the American Battlefield Trust’s Youth Leadership Team and has spent his formative years studying the often-overlooked 1862 Siege of Yorktown.

Sources:

Bacon, Charles Pumpelly, to His Aunt Stella, Spared & Shared 23, December 19, 2024, https://sparedshared23.com/2024/12/19/1862-charles-pumpelly-bacon-to-his-aunt-stella/.

Gunn, Thomas Butler, 1862. “Thomas Butler Gunn Diaries, Volume 21.” Oclc.org. Missouri Digital Heritage. 1862. https://mdh.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/CivilWar/id/27778.

Howard, Oliver Otis, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major General, United States Army (Baker and Taylor, 1908), Vol. 1, 218.

Lemont, Frank L., to J.S. Lemont, May 5, 1862.” DigitalCommons@UMaine. 2015. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/paul_bean_papers/17/.

“Report from Gen’l Wool on the Fall of Yorktown,” New York Times, May 5, 1862.

Stevens, C.A., Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865 (St. Paul, MN: C.A. Stevens, 1892).

Endnotes:

[1] Letter from Frank L. Lemont to J.S. Lemont, May 5, 1862.” DigitalCommons@UMaine. 2015. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/paul_bean_papers/17/.

[2] 1862: Charles Pumpelly Bacon to His Aunt Stella, Spared & Shared 23, December 19, 2024, https://sparedshared23.com/2024/12/19/1862-charles-pumpelly-bacon-to-his-aunt-stella/.

Well written article!

Excellent article of an understudied topic.

Excellent. Thank you for sharing these stories.

Excellent article!

Thank you so much! Perfect timing on the article as I did a video at Yorktown on the “Torpedoes” recently and found your article to help on research. I found the White Battery/Redoubt where the 40th NY was just yesterday and wanted to say Thank you!.

Hi Sean,

Great to hear! There is not much left of the White Redoubt, as I am sure you found. There are a few supporting trenches that remain untouched closer to Rte 17. The work’s footprint is still fairly visible on LiDAR. Unfortunately the Red Redoubt is totally gone and buried under the NPS maintenance building. Yorktown has many layers of history. Glad you are investigating an often overlooked chapter.