Stacking Arms “What Ifs?” – Episode III: “What If” An Ill & Frustrated Grant Had Broken Off Surrender Negotiations With Lee?

“It looks as if Lee still means to fight.”

“Why, it is a positive insult….”

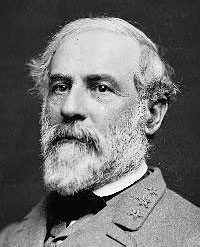

Ulysses S. Grant and his chief of staff, John A. Rawlins, respectively, reacting to Robert E. Lee’s response to Grant’s call for Lee’s surrender.[1]

The story of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865 is well-known. Richmond evacuated. The disastrous Sailor’s Creek battle. Escape blocked near Appomattox Court House. Grant offers generous surrender terms. A dignified stacking of arms.[2] Lee’s men return home with their commander’s stirring Farewell Address ringing in their ears.[3]

That peaceful Appomattox end scene might not have happened because of what Lee did on the very eve of surrender. What could be—and indeed at the time was— characterized as “underhanded” behavior by Lee[4] could easily have derailed that ending. The effusive praise history has afforded Grant for his generous conduct in Wilmer McLean’s parlor fails to consider an earlier critical decision Grant made that permitted that scene to take place at all. This tells that story.

During his pursuit of Lee’s army, Grant arrived in Farmville, Virginia the afternoon of April 7. While there, Grant learned that Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell (just captured at Sailor’s Creek) had confided that Lee had a moral obligation to seek terms. This dovetailed with a conversation that Grant had the day before with a relative of Ewell, who believed the war was lost, and “for every man that was killed after this… it would be very little better than murder.”[5]

It was time to end the bloodshed. Grant announced, “I have a great mind to summon Lee to surrender.”[6] Then he did so. Dated April 7, 5:00 p.m., Grant’s missive called upon Lee for “the surrender of that portion of the C.S. army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.”[7]

Lee replied. While disagreeing that further resistance was futile Lee, concurring with Grant’s desire to “avoid further useless effusion of blood,” wrote that “before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on the condition of its surrender.” [8]

There it was! Despite the minor hedging, Lee had asked for terms, accepting the inevitable. The end of the long national nightmare was at hand.

Lee’s reply reached Grant early on April 8.[9] Grant, possibly concerned that Lee feared his “unconditional surrender” reputation, assured Lee “that, peace being my great desire, there is but one condition I would insist upon, viz, that the men and officers surrendered shall be disqualified for taking up arms again against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged.”[10] After dispatching his note, Grant retired on April 8 expecting to accept Lee’s surrender the next day. Indeed, his message to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton made that confident prediction.[11]

Despite his optimism, Grant at this time was suffering significant pain. The campaign’s stress had caused a serious migraine headache. As Grant recounted in his Memoirs, “On the 8th … I was suffering very severely with a sick headache…. I spent the night in bathing my feet in hot water and mustard, and putting mustard plasters on my wrists and the back part of my neck….”[12]

What next happened certainly did not help Grant recover. Around midnight April 8, Grant received Lee’s response. Lee claimed that “I did not intend to propose the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, but to ask the terms of your proposition.” He had simply wanted to know whether Grant’s proposals would lead to the “restoration of peace.” Lee refused to meet with Grant to surrender, but if Grant’s proposal might “tend to the restoration of peace,” Lee would be pleased to meet Grant the next day.[13]

Rawlins, who had read Lee’s reply to Grant, was furious. Shouting, Rawlins accused Lee of bad faith and trickery, of trying to lure Grant into a forbidden discussion of politics, while falsely claiming that he (Lee) had not led Grant into believing that Lee was ready to surrender by asking for terms. Rawlins fumed: “It’s a positive insult. It’s an underhanded way to change the whole correspondence.” Noting that Lee also had said that he did not think “the emergency has arisen to call for the surrender” of his army, Rawlins growled that was a “lie,” and it was time to force Lee to give up.[14]

Grant, head pounding, temporized, suggesting that if he met with Lee he would end up surrendering. Rawlins reminded Grant that he had no authority to meet to discuss peace.[15]

Rawlins was right. Indeed, Grant recently had had his knuckles rapped after forwarding a proposal from Lee for a peace meeting. On March 3, Stanton shot back a sternly worded note that Lincoln absolutely forbade any meeting with Lee “unless it be for the capitulation of Lee’s army….”[16] Grant then had written to Lee, making it clear that Grant had no authority to discuss issues of peace.[17] Yet here was Lee, ignoring what Grant had told him, while pretending that he had not led Grant into believing that surrender was imminent, and trying to trick him into who knows what, perhaps attempting to buy time for his army to escape. Moreover, Sheridan had sent a dispatch that evening stating: “I do not think Lee intends to surrender unless compelled to do so.”[18] Lee’s note supported Sheridan’s conclusion.

Grant decided not to reply immediately, but to sleep on the problem. Grant’s effort failed. At 4:00 a.m., aide Horace Porter found his chief pacing the yard holding his head in both hands, reporting both that he had had very little sleep and “was still suffering the most excruciating pain.”[19]

In the end, the morning of April 9 Grant sent Lee another note. While declining the offered meeting, reminding Lee that he had “no authority to treat on the subject of peace,” Grant reiterated his desire for peace, strongly urging that not another life be lost.[20]

Grant’s was a soft letter, bereft of demand, threat, or ultimatum. By the time Lee received it, his breakout attempt had failed. After reading Grant’s message, Lee asked for a meeting to surrender. Lee directed his troops to set out flags of truce.[21] The rest, as they say, is history.[22]

But it might not have ended that way. What if, rather than sending a diplomatic response to Lee, Grant had adopted a more belligerent tone? Or, what if Grant had simply broken off negotiations, not replying at all, or in the alternative, decided to delay any response until Sheridan had bloodied Lee’s nose once again to force Lee to see reason?

The morning of April 9 Grant was in “excruciating pain.” He had not slept well, if at all. He was under enormous pressure. Just the day before he had told Stanton that Lee was about to surrender. Lincoln was expecting that.[23] Grant himself had expected that. Now all hope had been dashed. And it was all one old stubborn rebel’s fault.

Perhaps Rawlins was right. Lee had deceitfully misled Grant and was playing games to buy time to allow his army to escape. Lee was moving towards supplies, and the mountains, where he might find cover for fighting on even if he did not join with Joe Johnston in North Carolina. Grant’s own supply situation was tenuous. His men had done wonders, but he might be forced soon to stop and replenish his supplies.[24] It had been a mistake to treat Lee gently. Lee had responded by trying to take advantage of him.

Sheridan was right. Lee had to be forced to capitulate. If that meant more bloodshed, well, Grant had done his best to avoid such. His conscience was clear. Lee would be responsible for the coming butchery.

With this in mind, Grant might well have replied not to Lee, but to Sheridan, telling his most aggressive commander to bring Lee’s army to heel. Attack and keep attacking until all resistance has ceased. Then Grant would see how Lee felt about surrender.

Alternatively (or in addition), Grant might have sent a curt answer to Lee, perhaps reminding him that Grant had only recently told him he (Grant) had no authority to discuss peace, and chastising Lee for trying to entrap him in such a forbidden discourse. Grant also might have adopted Rawlins’s tone, expressing umbrage that Lee had claimed that he had not asked for surrender terms, calling out Lee for perceived duplicity. In effect, Grant would break off any further negotiations.

Receiving such a discourteous reply, how would Lee have responded? Now, Lee would have been effectively forced to beg even to be allowed to surrender. Lee might have realized that he had grossly overplayed his hand. He could expect no concessions from Grant. The humiliation of “unconditional surrender” would have been back on the table. He might end up a prisoner of war, to be paraded before the North. Would Lee’s pride allow him to go back to Grant and beg to be allowed to give up? And would Lee have hesitated before taking that step, desiring to confer with his officers, seek their advice? In the interim, however, Sheridan would have been on the attack. The end of the Army of Northern Virginia might not have come in Wilmer McLean’s parlor, but on the battlefield. What if Grant had not shown his final magnanimity?

[1] Ron Chernow, Grant (Penguin Press, New York, NY, 2017), p. 502; Mark M. Boatner, The Civil War Dictionary(David McKay Co., Inc., New York, NY, 1988), pp. 681-682.

[2] Elizabeth R. Varon, Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom At The End of the Civil War (Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2014), pp. 59, 77-78.

[3] “Gen. Robert E. Lee Farewell Address: General Order No. 9,” American Battlefield Trust, Civil War, Primary Source, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/gen-robert-e-lee-farewell-address.

[4] Burke Davis, To Appomattox: Nine April Days, 1865 (Eastern Acorn Press, reprint by Publishing Center for Cultural Resources, New York, NY, 1992), pp. 334-335.

[5] Davis, p. 296; Ulysses S. Grant, John F. Marszalek with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo, Eds., The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2017), pp. 713-714; Chernow, p. 499.

[6] Varon, p. 20.

[7] Varon, p. 20.

[8] Varon, pp. 20, 23 (emphasis supplied).

[9] Chernow, pp. 500-501; Varon, p. 29.

[10] Varon, pp. 29-30. Actually, considering what the U.S. had felt was Confederate bad faith in returning to the ranks POWs Grant had taken at Vicksburg, offering to parole Lee and his army represented a substantial concession by Grant. See “Exchanging Insults Rather Than Soldiers: Solomon Meredith, Robert Ould and the Breakdown of the Civil War Prisoner Exchange System (Part I),” Emerging Civil War Blog, January 13, 2025, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2025/01/13/exchanging-insults-rather-than-soldiers-solomon-meredith-robert-ould-and-the-breakdown-of-the-civil-war-prisoner-exchange-system-part-i/.

[11] Chernow, p. 501.

[12] Grant, p. 717.

[13] Varon, pp. 35-36.

[14] Davis, pp. 334-335.

[15] Davis, p. 335; Caroline E. Janney, Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army After Appomattox (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 2021), p. 15.

[16] Chernow, p. 474. Lee had suggested peace discussions by what he called a “military convention.” For the background of this scheme, see James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America(Barnes & Noble, Inc., New York, NY, 2004), pp. 501-505; Clifford Downey & Louis H. Manarin, Editors, The Wartime Papers of Robert E. Lee (DaCapo, New York, NY, 1961), pp. 897-898, 911-912; Chernow, p. 474; Stanton’s Letter to Grant, March 3, 1865, Encyc, https://encyc.org/wiki/Stanton%27s_Letter_to_Grant,_March_3,_1865.

[17] Longstreet, pp. 504-505.

[18] Davis, p. 333 (emphasis supplied); Varon, p. 35.

[19] Chernow, p. 503.

[20] Varon, p. 39.

[21] Varon, p. 41-45.

[22] Varon, p. 44, 49.

[23] On April 7, Grant had received a telegram from Lincoln. Lincoln had seen Sheridan’s April 6 message proclaiming that if “If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.” Lincoln had wired Grant: “Let the thing be pressed,” as if Grant were not already moving heaven and earth for that goal. Chernow, p. 498.

[24] Chernow, p. 501.

Great series of posts, Kevin. Really intriguing “What ifs.”

Brian, thank you kindly. (Just wait until I shock the audience by “killing off” R.E. Lee).

A great article.

Thank you, Mark. It was fun to write/speculate. More such on the way.

Great stuff! Confederate Major Charles Minor Blackford transferred to Richmond on 18 Sept, 1864. “When he was placed in a position to view behind the scenes, he soon determined that our cause was lost and that all our leaders knew it.” (Letters From Lee’s Army, page 275) Point being, Lee knew it was over long before he decided further resistance was futile.

Alan Nolan, in “Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History,” devotes an entire chapter (“The Price of Honor”) to the issue of when Lee himself felt that defeat was inevitable, and his actions in response.

It’s important to remember that Lee had ‘advisors’ on his staff (“Not yet”, said Longstreet, when he was asked straight up about surrendering!) and he had (Confederate) government officials he had to report to. He still took orders from them. Trying to finagle the best possible terms is understandable, and to be expected. To put this all as “that underhanded Lee” doesn’t seem credible, or fair. Given HOW Grant responded to Lee’s ‘change of intent’, it seems, to me anyway, that Grant night have anticipated such, and reacted accordingly. Ultimately, Grant won out, and for Lee’s troops, the fighting was indeed over.

Now, had Grant just called everything off and ordered that Lee be attacked, I think nothing would have ultimately changed, except for more bloodshed and the surrender being put off a few days or so. But Lee surrendered because it really was all academic at that point.

Doug, I do not disagree with your points. Lee was indeed trying to get the best terms he could, while trying to get out of his bad tactical situation. On the other hand, I can imagine (as I do in the post) a situation in which Grant reacted differently than he did in history. Grant too was under pressure, in physical pain, while he had Rawlins yelling at him. Also, as Grant later told a reporter while on his around the world tour, he feared that if did not bring Lee to heel within the next day, he might have to break off the pursuit for lack of supplies. Whether Grant really would have done that is questionable, but I can imagine him saying to heck with this Lee who is causing me all these troubles, I’ll let Sheridan go get him.

Grant had all the cards here and he clearly kept his own counsel in this matter — inspite of recommendations from a characteristically aggressive Sheridan and the ever-complaining Rawlins, his chief of staff … Grant clearly had the ANV in the bag and there was no reason for him to incur anymore casualties by attacking Lee … conversely, Lee was clearly angling for best terms he could get — no dishonor there … another great post. thanks