The Devious Deceiver – Chaplain Fr. Joseph Bixio S.J.

ECW welcomes guest author Rev. Robert Miller.

Civil War readers know that the conflict was replete with fascinating characters and unique personalities. From New York politician and general Daniel Sickles and the enigmatic Nathan Bedford Forrest, to the stern Presbyterian “Stonewall” Jackson and fiery Sojourner Truth, true characters abounded in all aspects of the war. However, when considering those colorful people – so many of whom pushed mid-19th century social boundaries, sensibilities, and traditions – one might not expect to see clergy and ministers.

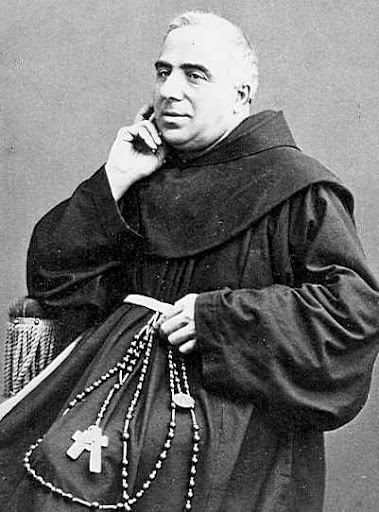

The bias exists both then and now that “good religious people” spend their time praying to God and are out of touch with real issues, far beyond the mundane exigencies of everyday life. This could not be farther from the truth! Those who chose a professional religious career in the Civil War era were as unique, mysterious, and quirky in their personalities as any civilian – perhaps even more so at times! In reviewing the often overlooked religious perspective of the Civil War, some truly distinctive and unique personalities emerge from the pages of history to grab our attention. One such character was a curious Jesuit priest named Joseph Bixio, an “informal” Catholic chaplain who, whichever side he chose to operate on, truly acted out of his own unique agenda.

All 126 Catholic Civil War chaplains (total numbers for both sides) faced unique challenges during the war years, being a minority in a primarily Protestant country and chaplaincy (only 3 percent). However, these courageous men helped break down century-old barriers of historic religious prejudice and bias. Some became very well-known: William Corby (88th New York Irish Brigade), Abram Ryan (poet of the Lost Cause), James Sheeran (14th Louisiana), and John Bannon (1st Missouri) among them. But of all Catholic priest-chaplains, no story is as colorful, checkered or filled with devious chicanery as that of the Italian Jesuit priest Joseph Bixio, S.J. (1819-1898).

Born in the Savoy region of Italy in 1819, Bixio was the brother of Nino Bixio, Giuseppe Garibaldi’s right-hand man in the 19th-century struggle for Italian unification. Always a somewhat restless soul, as a young man Joseph was called “a mischievous, troublesome hooligan,” street-wise and clever. Nevertheless, he eventually felt drawn to religious life, entering the Jesuits, and coming to the United States as a student when the that religious order were expelled from the Kingdom of Sardinia (1848).

Bixio was ordained in 1851, then worked in Virginia, Maine, and California as a “circuit-rider” for several years. Leaving California with “some bad feelings towards his superior” (his restless independence frequently led to tensions with his order), Bixio returned east, apparently intrigued and attracted by the energies and issues surrounding the looming war.[1]

As the Civil War began, he was serving in a parish which bordered Virginia and Maryland. At the battle of First Manassas, the smooth-talking Bixio seems to have played some helpful (though not totally verifiable) role in assisting the Confederacy, by giving information about the Union to the Confederates under Gen. Joseph Johnston.[2] However, after that battle, Bixio found himself stranded on the Virginia side of his parish, unable to return to the northern (Maryland) side. But, according to a January 1862 letter from Hippolyte Gache, a fellow Jesuit and chaplain of the 10th Louisiana (who had just met Bixio while in Richmond), “this didn’t bother him a bit; he has simply volunteered as a Confederate chaplain.”[3] Though his exact activities are unknown, by the spring of 1862 it seems that Bixio had developed a curious knack and talent for “slipping back and forth across the Federal lines,” using his Italian charm, Roman collar, and religious identity as “passports.” However, as Jesuit historian Cornelius Buckley noted, “it is fairly certain, too, that Bixio did not sneak back empty-handed.”[4]

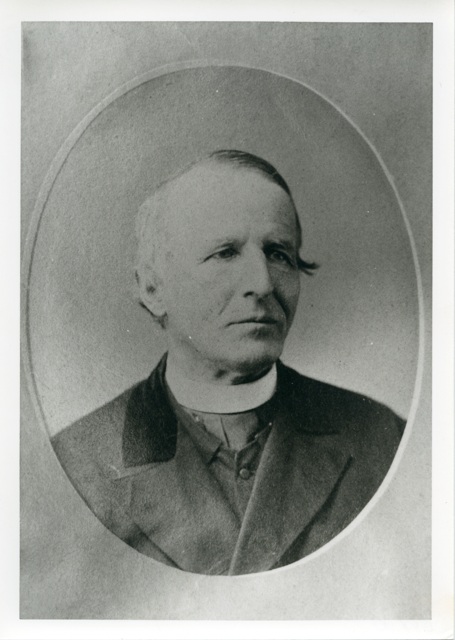

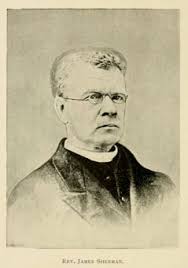

In the spring of 1862, priest-chaplain James Sheeran (14th Louisiana) noted in his journal that Bixio had again sneaked across the lines and “gained the hearts of officers and soldiers” in the Union army. But by June 1862, the Jesuit was apparently back with the Confederates at the battle of Gaines’s Mill, being referred to (without name) in the journal of a captain of the 11th Alabama whose wound had been dressed by a priest “who had a great deal of experience in the Italian army,” which could only have been Bixio.[5] In September 1864, Sheeran once again referred to Bixio, noting that he was “now playing Yankee chaplain and drawing federal rations in Winchester, Virginia.”[6] By this time however, Bixio’s games finally began to have some serious consequences, although he personally would never pay the price for his deceptions.

In the fall of 1864, Bixio had begun posing as the Italian Franciscan chaplain of the 9th Connecticut, Leo Rizzo de Saracena (1833-1897), whose credentials and uniform he literally had taken from Rizzo’s tent when he was deathly ill in the hospital with typhoid. Using this disguise, Bixio tricked Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan into giving him several wagon-loads of supplies, which he then brazenly drove into Confederate lines up to Staunton, Virginia. Although Bixio got away with this, when the deception was discovered, it was other people who suffered. Leo Rizzo himself was first accused of espionage and treason by an enraged Union general, but was able to provide witnesses as to his serious medical issues at the time. But James Sheeran of the 14th Louisiana was not so lucky: A furious Sheridan had Sheeran arrested after catching him as he ministered to the wounded of both sides after the battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864. Without being told why he had been arrested (until his final contentious interviews with Sheridan after his release much later), Sheeran was imprisoned for four months under truly horrible conditions in two Baltimore prisons.

St. Bonaventure University.

After great personal troubles, and with his physical condition rapidly failing, Sheeran managed to use his connections with his own religious order (the Redemptorists) and James McMaster, editor of the New York Freemans Journal, to finally secure his release. However his chaplain’s career was finished, and he ended the war in a Richmond infirmary.

Yet the devious Bixio evaded all consequences, after receiving a “polite” message in Staunton, Virginia from an unidentified Union general that he would be “hanged from the first tree” if he was caught again. The sly Italian had the common sense to stay away from the Valley and Sheridan and never was caught. After the war ended, he traveled to Georgetown with a trunkful of useless Confederate money expecting to found a college there, but again left the East for California in October 1866.[7]

To the end, the Italian Jesuit retained his cunning and charisma, charming Archbishop Joseph Alemany (San Francisco), becoming his confidant, working at the Jesuit College in Santa Clara, and even founding several parishes there. But his restless spirit still not quieted, Bixio left for Australia in 1878 in a failed effort to teach there, only to return to California two years later. Ironically praised in his final years for “his incredible nobility, coming and going about the town and valley, familiar to all and liked by all,” Bixio remained at Santa Clara College until his death in March 1899.

Although not considered an official Civil War chaplain, Joseph Bixio certainly had a colorful history, whatever his true nature and intentions. Perhaps this most idiosyncratic of all the Civil War Jesuits was best summarized by one historian of the order who called him “every bit as ingenious and resourceful as he was double-dealing and cunning.”[8]

Robert J. Miller is a Catholic priest of 49 years, retired from 35 years of inner-city Chicago ministry. He has master’s degrees in religious education and divinity, has authored 5 books on spirituality and faith, and was an adjunct professor of Church History at the University of St. Mary of the Lake. A former President of the Chicago Civil War Round Table, he frequently speaks on topics of spirituality, history and Civil War religion. His 2007 book, Both Prayed to the Same God: Religion and Faith in the Civil War, was the first book-length overview of the topic. His newest book Faith of the Fathers: A Comprehensive History of the Catholic Chaplains of the Civil War has just been published by Notre Dame Press (April 2025).

Endnotes:

[1] Cornelius Buckley S. J., “Joseph Bixio: Furtive Founder of the University of San Francisco,” California History, Vol. 78, no. 1 (Spring 1999), 14-25.

[2] An English Combatant, Battlefields of the South: from Bull Run to Fredericksburg, (London: Smith, Elder and Company, 1863) Vol. 1, 280.This anonymous English lieutenant said “Johnston and Beauregard escaped death or capture at Manassas” by heeding the advice of an unnamed Jesuit priest, who clearly was Bixio.

[3] Hippolyte Gache, S.J., A Frenchman, A Chaplain, A Rebel: The War Letters of Pere Louis Hippolyte Gache, S.J. (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1981), 92.

[4] Buckley, “Joseph Bixio,” 98.

[5] George Clark, A Glance Backward, or Some Events in the Past History of My Life (Houston: Rein and Sons, 1920), 23-24.

[6] James Sheeran, C.Ss.R., Confederate Chaplain: A War Journal, ed. Joseph Durkin (Milwaukee: Bruce, 1960), 100-102, 153-56, 160.

[7] “Obituary of Joseph Bixio,” Woodstock Letters, XVIII (1889), 247. Based on location, time, and connections, the author believes this general may be Benjamin Butler.

[8] Gache, Frenchman, 97-99.

Bixio was quite the character. His obituary says he was “arrested as a spy, but was finally honorably released.” After the war he served as an pastor at San Francisco’s St. Joseph’s Church and for two years at Santa Clara College. (“A Pioneer Priest Dead,” Daily Alta California, 4 Mar 1889, p 5, col 4, https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=DAC18890304.2.40&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN——–) Could he be the same Joseph Bixio that the University of San Francisco credits with serving on the boards of the institutions that became the University of San Francisco and Santa Clara University?(https://myusf.usfca.edu/provost/The-Jesuits-and-Native-Communities)

Bixio’s brother Nino was also a controversial character whom I encountered during the research and writing of my current book project involving Garibaldi. His actions in Sicily in 1860 were ferocious, including executing five civic officials in the town of Bronte, including the mayor. Nino Bixio’s harsh actions reverberate even today and form a stain on Garibaldi’s heroic reputation in Italy. Before the voyage of the Thousand to Sicily, the shirtless Bixio spoke to the troops under his command: “I’m young. I’m thirty-seven years old, I’ve been around the world. I’ve been shipwrecked; I’ve been a prisoner; but here I am and I command! Here I’m everything, Czar, Sultan, Pope. I’m Nino Bixio!”

Fr. Miller, wonderful story, and well-told. We look forward to you speaking to the Roanoke (VA) Civil War Round Table in the future.

As one who was college educated by the Jesuits, I find this behavior not uncommon. In fact, it could be categorized as par for the course.

As one who was college educated by the Jesuits. I find this conduct not uncommon. In fact, I would call it par for the course.