The Last Major Confederate Surrender: Smith, Buckner, Shelby, and Price Debate Their Options

Dating when the American Civil War ended is a point of debate. All that can be agreed upon is that the fall of Richmond and Petersburg, followed quickly by Robert E. Lee’s submission at Appomattox, created a chain reaction that assured collapse. Lee and his ability to hold Petersburg and Richmond was the hope the diehards clung to in 1865. Now it was gone.

Dating when the American Civil War ended is a point of debate. All that can be agreed upon is that the fall of Richmond and Petersburg, followed quickly by Robert E. Lee’s submission at Appomattox, created a chain reaction that assured collapse. Lee and his ability to hold Petersburg and Richmond was the hope the diehards clung to in 1865. Now it was gone.

Aiding this was William Tecumseh Sherman’s advance through North Carolina and the fall of the last major coastal bastions at Charleston, Wilmington, and Mobile. James Wilson ripped through Alabama and into Georgia and Florida, destroying the last of the South’s industrial base. Joseph Johnston, who was never as committed to the Confederacy as others, surrendered on April 26 after long negotiations. The last major force east of the Mississippi River was surrendered by Richard Taylor at Citronelle, Alabama, on May 4. The next day, Jefferson Davis dissolved the Confederacy and was himself captured on May 10, the same day Florida’s forces submitted.

Even as the Confederacy fell apart, some wanted to continue. Many were looking to their political future. Taylor observed with his usual sarcasm that “many Southern warriors, from the hustings and in print, have declared that they were anxious to die in the last ditch, and by implication were restrained from so doing by the readiness of their generals to surrender. One is not permitted to question the sincerity of these declarations, which have received the approval of public opinion by the elevation of the heroes uttering them to such offices as the people of the South have to bestow; and popular opinion in our land is a court from whose decisions there is no appeal on this side of the grave.” Taylor believed such dramatic statements were hollow.

Johnston had a spat with Thomas Clingman, who was perhaps looking to his political future. Clingman wanted to “make this a Thermopylae” rather than surrender to Sherman. Johnston retorted that he was “not in the Thermopylae business.” Johnston had already told Davis it was over, and Taylor told his men not to turn guerrilla lest they “be hunted down like beasts of prey.” Kirby Smith’s Trans-Mississippi Department was different. It was filled with guerrillas and rough-hewn cavalry. If a true guerrilla war or insurgency were to happen, it would be here, where there were actual diehards as well as men who feared retribution. They might keep fighting.

Smith was tired of his command and asked for reassignment months before. His department was under constant strain and reeling from Sterling Price’s disastrous Missouri invasion. Supplies were dwindling, inflation was high, the men were unpaid, and many were leaving. Smith resorted to freely executing deserters, but it did little good. Some 50 men in the 29th Louisiana left as deserters from east of the Mississippi streamed in, bringing stories of disaster at Nashville and Petersburg.

Not until April 19 did Smith know of Lee’s fate when John Pope informed him. It was kept from the men until April 21. The initial reaction from the top brass was to keep fighting, confirmed in a meeting on April 29 in Shreveport. That same day, George Flournoy, backed by Louisiana Governor Henry Allen, said that Smith planned to surrender the department to Pope. Adding to Flournoy’s case, John T. Sprague, Pope’s chief of staff, was at Alexandria waiting for Smith to submit. Smith denied that he wanted to yield, but now there were rumors in a chaotic situation.

Price wanted to arrest Smith. However, Smith’s spies warned him, and Smith ordered Price to Washington, Arkansas, to get him out of Shreveport. How serious Price was is debatable, but it is unnerving that he even contemplated anything. Smith, though, decided to hold on in case Davis made an escape.

Smith had some 50,000 men in arms, but once the news of Lee’s surrender arrived, the department’s shaky discipline and morale collapsed. Desertion accelerated. Officers left and were followed by their men, some destroying their weapons. Lawlessness was so bad that Smith and his staff did not leave their quarters at night.

Texas troops abandoned the cause first. John N. Edwards, a member of Joseph Shelby’s staff, insulted them in 1867 in strong words, that it “never occurred to her galloping, spur-jingling, half-horse, half-alligator Yahoos, that some bastard Federal lieutenant would erect branches of his negro bureau in every available town, and through the magic of a shoulder-strap whisp away the half dozen revolvers girt about them, and the fearful yells with which the long-haired man-eaters were wont to extinguish the ‘Yankees’ and devour the ‘Dutch.’ Where now are the ‘three-foot’ bowie-knives? Where the coiled lassoes for fancy work about the skirmish lines? Where the unterrified, unextinguishable, unadulterated, unuttterable Tex-i-ans, who swore as an excuse for clandestinely disbanding, that if the ‘Yankees dared to pollute the sacred soil of Texas, every rivulet should run with blood and every bayou should be a battle-field ?’ Herding harmless cattle in the sunlight, and promising great things some day — subjugated, oppressed, trampled upon, and despised by the very ‘Yankees’ to whom they marched three hundred miles to surrender, and for whose sakes their guns were consumed in the prairie grass, and their swords beaten into plowshares.”

On May 8, Sprague met Smith at Shreveport and told him Johnston had surrendered. Smith wavered, knowing there was no major army east of the Mississippi outside of Taylor’s forces, which had just taken a beating at Mobile and Selma. Regardless, Smith turned down Pope on May 9, in part because Pope’s message was too harsh. Meanwhile, morale utterly collapsed in the department at the news of Johnston’s surrender, and now most generals and politicians decided it was truly over. In a May 13 meeting at Marshall, Texas, the various governors advised Smith to surrender.

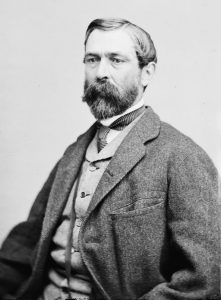

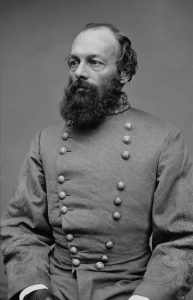

Despite all the bad news, Shelby would not give up. He wanted to replace Smith with Simon Buckner. The plan was to keep on fighting until driven across the Rio Grande, where the Rebels would help either side in the ongoing Mexican Civil War and from there found “an Empire or a Republic.” When Shelby told Smith his plan, Smith cried and promised to hand command to Buckner, who agreed to take command only if Smith gave it up willingly.

Buckner apparently agreed with Shelby at this point, but there is some doubt about how serious he was. However, most soldiers wanted to give up, and Buckner was fast losing hope, if he had any. Smith, meanwhile, at Shelby’s behest, sent William Preston to Mexico to apprise him of the situation. There were vague hopes of Mexico letting the Rebels in or even asserting some authority over Texas. Smith also expected Davis to arrive via Cuba, not knowing yet he was in Wilson’s custody. At the same time, Smith sent a letter to Pope to reopen talks.

That the war would end was certain, but the situation was in flux and dangerous. The next few weeks would determine if the bloodshed would end sooner or later. And in this situation, Buckner would play a key role.