The Last Major Confederate Surrender: Submission in New Orleans, May 26, 1865

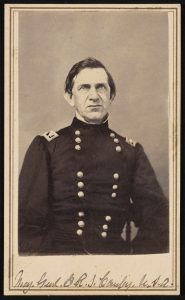

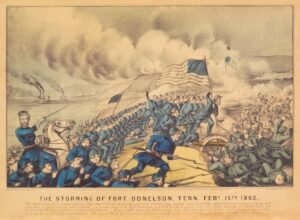

Simon Buckner had taken a tortured road to his 1865 command. He tried to get Kentucky out of the Union and had the sad duty of surrendering Fort Donelson. He spent most of the war in district commands, but led a corps at Chickamauga. Buckner was assigned to the Trans-Mississippi Department on April 28, 1864, at Kirby Smith’s request. Jefferson Davis appears to have wanted Buckner to help in an invasion of Missouri, where many Kentuckians settled before the war.

Simon Buckner had taken a tortured road to his 1865 command. He tried to get Kentucky out of the Union and had the sad duty of surrendering Fort Donelson. He spent most of the war in district commands, but led a corps at Chickamauga. Buckner was assigned to the Trans-Mississippi Department on April 28, 1864, at Kirby Smith’s request. Jefferson Davis appears to have wanted Buckner to help in an invasion of Missouri, where many Kentuckians settled before the war.

Buckner eagerly accepted his new assignment, crossing at Tunica, Louisiana, on June 13, 1864. He did well as essentially Smith’s second in command and was popular with the men. For his efforts, Buckner was promoted to the Confederacy’s second-highest rank at Smith’s insistence. However, Buckner tried to cross troops to the east bank, but it was determined only small groups could come over. An idea by P.G.T. Beauregard to strike at New Orleans in February 1865 was squashed by Smith and Buckner.

Fighting was at a near end. CSS Webb, which made a run from Shreveport to the gulf, was almost successful before being destroyed near the mouth of the Mississippi on April 25, in one of the most dramatic naval actions of the war. The skirmish at Palmito Ranch near Brownsville, Texas was brought on by a controversial Union attack. On May 17 Smith went to Houston without giving Buckner command, leaving before an angry Sterling Price could confront him. He intended from there to gather his forces and wait for Davis, who was said to be making his way west.

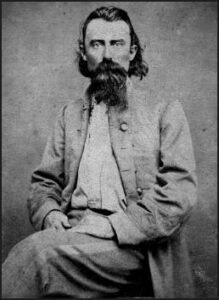

In Texas, Smith found out almost all the troops under John G. Walker and John Magruder had disbanded. Smith called himself “a commander without an army.” John N. Edwards noted that in Texas, “everything was collapsing as fast as a patient in the last stages of cholera.” Joseph Shelby found his men having to resist marauding ex-soldiers, particularly in Tyler, Texas. His men maintained order where they could, but Texas was too vast, and its unionist element was asserting itself.

Price, against Smith’s orders, went to Shreveport. By then, the remaining Louisiana and Texas Confederates were deserting, many turning to banditry. Rations were dwindling, which caused the 26th and 28th Louisiana to evaporate after a march from Natchitoches to Mansfield. The 26th Louisiana ripped apart their banner, each man getting a piece as a memento. Their commander, Winchester Hall, burned the flagstaff.

Price, against Smith’s orders, went to Shreveport. By then, the remaining Louisiana and Texas Confederates were deserting, many turning to banditry. Rations were dwindling, which caused the 26th and 28th Louisiana to evaporate after a march from Natchitoches to Mansfield. The 26th Louisiana ripped apart their banner, each man getting a piece as a memento. Their commander, Winchester Hall, burned the flagstaff.

Only the Missouri and Arkansas troops remained, and they asked Buckner to make an orderly surrender. For his part, Buckner was appalled by the chaos in the area and thought only Federal troops could restore order. Some of it was self-inflicted. The 3rd Louisiana, one of the best regiments, only dissolved on May 19-20 when they were placed under guard. The enraged men proceeded to disperse and liberally loot. Only a small part of the 17th Louisiana remained.

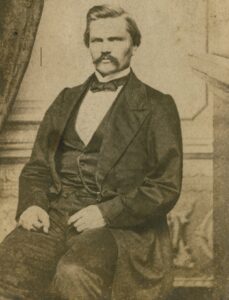

Buckner’s surrender would be a relief to E.R.S. Canby, the overall commander west of the Mississippi and along the Gulf Coast. As late as May 20, Peter Osterhaus, Canby’s chief of staff, reported that Smith and Buckner planned to keep fighting. By one account, an alarmed Canby was preparing to drive into Texas on May 27.

In reality, May 20 was when Price decided to surrender. Price went with Buckner and each man taking part of their staff. Shelby, after hearing this, made for Mexico. As for Osterhaus, he received word from Buckner on May 21 and informed Canby, who was in Mobile. Buckner was not a moment too soon. Independent of Buckner, Harry Hays on May 23 had already sent Joseph Brent to talk with Francis Herron, commander at Baton Rouge, about surrendering Louisiana. John Magruder also had a delegation sent to surrender Texas, but they did not arrive in time.

Upon reaching Baton Rouge on May 24, Herron, escorted Buckner, Price, and Brent to New Orleans. Canby and Buckner arrived in New Orleans on May 25. Buckner did not dally. He went straight to the St. Charles Hotel. The building was a massive structure, built atop a previous hotel that burned down. It was here that Benjamin Butler made his headquarters, and it remained so for the Union forces in Louisiana. It was here the Bayou Teche, Port Hudson, and the Red River campaigns were planned. Today it is the site of the massive Place St. Charles. There is no historical marker for what unfolded there.

To aid in the talks, Buckner asked for Richard Taylor to assist. He was in New Orleans waiting for his family. He had established good relations with Canby, who also wanted Taylor there. However, Taylor had exchanged barbed words with Osterhaus weeks before. There might be another dramatic exchange ripe for newspapers and memoirs.

The terms were the same Ulysses S. Grant gave Robert E. Lee and which John Pope offered Smith weeks earlier. Buckner tried to get better ones, but it went nowhere, and William Tecumseh Sherman’s generous terms to Joseph Johnston would be impossible. The Rebels agreed to terms that night, but not until May 26 would everything be signed and finalized. By all accounts, the meeting was relatively pleasant and without any humorous or dramatic incidents. There was no pathos in New Orleans. No Sherman hogging whiskey, Taylor sparring with Osterhaus, nor Grant asking Lee if he remembered them meeting back in Mexico.

Osterhaus signed for the Union, as he was Buckner’s Union equivalent. Osterhaus recalled, “With these capitulations, the great war came to its conclusion. To me, it will always be a highly valued recollection, that it was my good fortune to set my name under these final agreements.” As for Taylor, he wrote, “So, from the Charleston Convention to this point, I shared the fortunes of the Confederacy, and can say, as Grattan did of Irish freedom, that I ‘sat by its cradle and followed its hearse.’”

There would be another hearse on May 26. That same day, some of the Union’s last executions occurred, as ten men, eight from the 52nd USCT, were hanged for murder. The other two were also from USCT outfits.

Back in Louisiana, Buckner inevitably thought back to Fort Donelson, saying it “was but an illustration of what I did here.” There was the parallel of him being left by a superior to carry out the act. Buckner also surrendered on his initiative at both places. Unlike Fort Donelson, though, his men were mostly eager to give up. Just as Nathan Bedford Forrest escaped Fort Donelson, Shelby fled to Corsicana, Texas.

Smith considered going to Mexico and asked Buckner to join him on May 28, unaware Buckner had already given up. On May 30, Smith gave up all hope of good terms and contacted John Sprague. On June 1, Smith went to Galveston and found out Buckner had already surrendered. The next day, he finalized the capitulation in Galveston harbor aboard USS Fort Jackson, adding only that Confederates be allowed to make a home out of the country.

Smith considered going to Mexico and asked Buckner to join him on May 28, unaware Buckner had already given up. On May 30, Smith gave up all hope of good terms and contacted John Sprague. On June 1, Smith went to Galveston and found out Buckner had already surrendered. The next day, he finalized the capitulation in Galveston harbor aboard USS Fort Jackson, adding only that Confederates be allowed to make a home out of the country.

By then, Arkansas was in chaos, and those troops were dissolving. On June 2, Price told his Missouri men it was over. They were among the few to maintain some discipline and reacted with joy, dejection, or anger depending on the man. June 3 saw the Red River squadron surrender. On June 6, Herron arrived in Shreveport. Slavery was ended in Louisiana on June 10 and in Texas on June 19.

On June 2, Shelby’s men split up, some going to Shreveport and the rest going with him from Waco to Austin. At some point, Price joined him. At San Antonio, they found the city in the clutches of disorder and a number of prominent Confederates milling about, including Smith, Magruder, Thomas Hindman, Hylan Lyon, Danville Leadbetter, Cadmus Wilcox, Henry Allen, Isham G. Harris, and others. From there they went to New Braunfels with these fellow Confederates in tow. Smith led the vanguard.

Shelby reached the Rio Grande at Eagle Pass with 1,000 men. The Confederates dumped their flags in the river on July 4, 1865. Whatever hopes they had of service in Mexico or raiding Texas ended as they were disarmed after crossing over.

Many blamed Smith and Buckner for what befell the department, even though Smith went with Shelby to Mexico. Edwards, ever ready with an insult, thought Smith was “totally destitute of enterprise, without the faint whisperings even of ambition ; slow, nerveless, indifferent ; more of an Episcopalian preacher than a revolutionary leader; he demoralized the entire department, mildewed the army, disgusted his subordinates.” Of Buckner, he wrote, “His enthusiasm was short lived, his determination was never compact, his romance was a practical kind, and he had the mournful satisfaction of surrendering the first and the last army of the subjugated and destroyed South.” Edwards, though, penned those words during the height of Southern bitterness, and the reality was Buckner and Smith had little choice.

While Smith left for Mexico, Buckner judged it undignified to flee. He oversaw the paroling of the department. While he thought he would parole 38,000, it was only around 17,000 due to desertions, exiles, and men going home directly. The work was done by June 8. Buckner wrote a farewell to his men, soldiers he had known for nearly a year and had not led into battle, but who retained great confidence in him though no longer in the cause and its chances. He told them to “cultivate friendly relation with all, abstain from all hostile acts, and discountenance every attempt at disorder.” The next day, he wrote a farewell to his staff. He then returned to Kentucky.

Several history books have made a case for May 26 as the war’s true end. While the department was dissolving, it could have held out under different circumstances, particularly if Smith made plans in regard to Mexico weeks before Appomattox. Collapse east of the Mississippi came too fast to a department already in a leadership crisis because Smith was dejected, Buckner lacked will, and Price was under a cloud due to his disastrous 1864 Missouri invasion. Only Shelby and his brigade, probably the best west of the Mississippi, soldiered on, having a leader of iron will commanding a coherent fighting force. Stand Watie also held out until June 23, but that had more to do with the politics of Indian Territory than a true diehard last stand.

There is a contingent of historians who say the war never ended. The nation is still divided along the same lines, and Reconstruction saw an insurgency. However, Reconstruction was not an insurgency, as the American army was not targeted. It was more a manifestation of the type of political violence that was already common in America before the war, which already had a racial dimension.

One would do better to compare Reconstruction violence to New York City and New Orleans in the 1850s, than they would Iraq or Vietnam. There have been massacres, riots, and skirmishes since 1865, and beyond Reconstruction. There would be Colfax, Haymarket, Tulsa, and Ruby Ridge, violence across the political spectrum, with varying dimensions of race, class, ideology, and even religion. However, an actual war, where Americans participated in mass, consistent, and constant organized violence, was at an end the moment Buckner and Osterhaus signed in the St. Charles Hotel.

Excellent. There has always been incredible untidiness in American history that is more spontaneous in nature than conspiratorial and exquisitely planned. The decorous nature of Appomattox under the gimlet eyes of Grant and Lee was certainly not the norm out West.

The author is certainly correct in differentiating America’s long history of civic violence from the Great Insurrection.

Enjoyable read.

What a great closing Just so we don’t forget, the 60’s had substantial organized consistent antiwar and antidiscrimination violence, murder of leaders, burning of sections of cities, teargas being in great demand, culminating in Kent State civilian killings, but I say that in a lest we forget vein, not to take away from this brilliant series of articles.