Book Review: Hope Never To See It: A Graphic History of Guerrilla Violence during the American Civil War

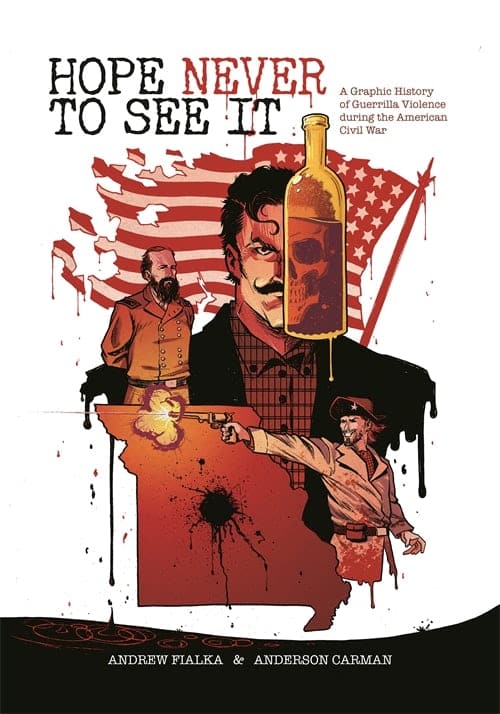

Hope Never To See It: A Graphic History of Guerrilla Violence during the American Civil War. By Andrew Fialka and Anderson Carman. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2025. Softcover, 198 pp. $19.95.

Hope Never To See It: A Graphic History of Guerrilla Violence during the American Civil War. By Andrew Fialka and Anderson Carman. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2025. Softcover, 198 pp. $19.95.

Reviewed by Lee White

Hope Never To See It: A Graphic History of Guerrilla Violence during the American Civil War by Andrew Fialka and Anderson Carman is a surprising recent release by the University of Georgia Press that definitely proves the old adage, “Don’t judge a book by its cover.” In a brilliant and bold move, and using an unconventional format—a graphic history—the authors are able to effectively offer readers (and of course, viewers) an alternative take on an extremely grim and dark chapter of the American Civil War. Scholarship on Civil War guerillas has blossomed over the past couple of decades, producing some excellent studies that have expanded our understanding about many facets of irregular warfare from 1861-1865. But, Hope Never To See It certainly blazes a brand new trail of its own.

The bloody guerrilla conflict that ravaged Missouri spawned a type of warfare where atrocities were commonplace and the distinctions between civilians and soldiers often blurred to the point of blending. Illustrator Anderson Carmen makes effective use of the graphic format to emphasize the visceral violence that permeated this brutal style of fighting in ways that words often fail to properly convey. Since history did not leave us many images or photographs of the atrocities and depredations committed by irregular soldiers, modern artwork can help us see the often indescribable brutality of the guerrilla war.

Dr. Andrew Fialka focuses on two brutal chapters of this ugly war. The first, a two week 1864 murder spree by US detective/spy Jacob Terman, alias Harry Truman, and perpetuated under the guise of his attempt to capture Confederate sympathizing guerrilla leaders that turns into a personal campaign of robbing and killing. The second examines the notorious Confederate guerrilla chief William T. “Bloody Bill” Anderson’s infamous 1864 raid on the town of Centralia, which resulted in the massacre of 22 unarmed US soldiers taken from a passing passenger train. Anderson then followed up that atrocity by ambushing a force of Missouri Unionists that added 125 more deaths. Both of these gruesome stories work well for the graphic history format, neither pulling any punches when it comes to the violence that each side perpetuated in this conflict.

However, do not mistake Hope Never To See It as simply an extended comic book. On the contrary, this graphic history book contains proper source citations, and all of the image dialogue is based on sound primary sources, including court records from Terman’s prosecution. Modern academic scholarship related to Missouri’s guerrilla war serves as a solid foundation throughout the book. Additionally, Fialka provides a scholarly and well written introduction and conclusion that help place the two stories in proper context of the broader history of guerrilla warfare in this border state.

A number of excellent maps highlight the text and set the stage for the events that transpire within its covers by illustrating the spatial effect of Order #11, which was intended to combat guerrilla violence within the state. One particularly intriguing map shows the increase of guerrilla activity leading up to the tragic events at Centralia. Other highlights of the book include an artist sketchbook and a thorough bibliography.

Hope Never To See It is an innovative book. It opened my eyes to a part of the war that I had only a passing knowledge about. Fialka, Carman, and the University of Georgia Press should be commended for thinking outside of the box with Civil War scholarship and exploring ways to bring history to a wider, more diverse, and likely younger audience with subjects and studies like this that often go untouched by traditional histories of the war and battle narratives.