Seizing Grant’s Ship?

ECW welcomes back Arie De Young.

In the modern day, John Marshall Harlan is best known for his time as a justice on the United States Supreme Court, particularly for the fiery and prescient dissent he rendered in response to Plessy v. Ferguson. Before he sat on the bench of America’s highest court, he served his country in the Civil War. As the colonel of the 10th Kentucky Volunteer Infantry, he participated in several of the war’s famous moments, including the battle of Mill Springs and John Hunt Morgan’s Christmas Raid. According to him, however, he encountered an even greater brush with fame during the conflict.

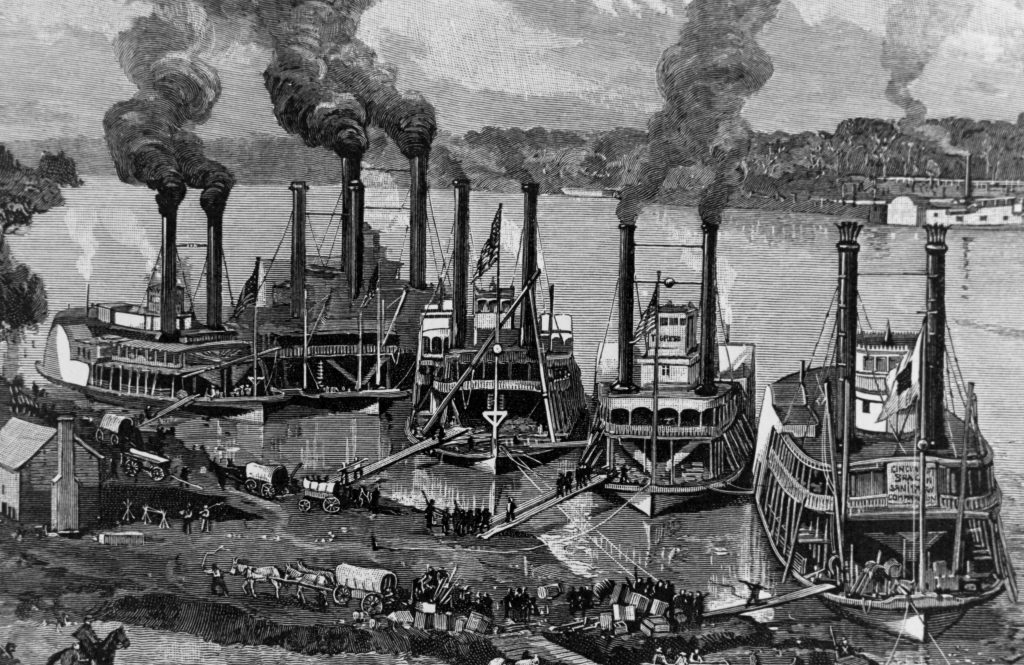

His regiment was serving in George H. Thomas’s division of the Army of the Ohio in April 1862. When the battle of Shiloh began Ulysses S. Grant called on reinforcements from the Army of the Ohio; they hurriedly marched to his aid. Struggling through heavy rain and flooded creeks, they eventually boarded a steamboat that expedited their transport to Pittsburg Landing. Nevertheless, when the regiment arrived on April 7, 1862, the battle had already concluded in a Union victory.[1] With his men exhausted and drenched, Harlan recalled what happened next in a 1911 letter he wrote to his son, Richard Davenport Harlan.[2]

The soldiers were ordered off the transport and to make camp at the landing. Many grumbled against this as “a cruel order,” however, as the rapid speed of their transport and crowding onto the steamboat had necessitated that they leave behind their supply wagons, including most pressingly their tents.[3]

Left with only their “ordinary army blanket,” Harlan’s men improvised. Some of them walked to where the army’s supplies were and procured several hay bales. Once opened, the hay was used to cover the soaked ground. This was sufficient, Harlan noted, that “in a few moments they were all asleep.”[4]

The ordeal wasn’t over for them, however. The rain started once more in the middle of the night. Even with their hay beds, the conditions became insufferable, and the men awoke. The 10th Kentucky was soaked once more as the rain drizzled on them. Harlan noted, “I determined that the situation should be changed, whatever might be the consequences to me.”[5]

Salvation seemed to loom in the river right beside them. Harlan recalled, “Right before my eyes was a large steamboat, brilliantly lighted, with no one occupying it except a few officers and subordinates.”[6] Ordering his men into a line, Harlan marched them towards the boat. When they arrived, they were sternly denied entry at the plankway.

Outraged, Harlan bellowed, “Who dares to stop my men or to interfere with my orders?”[7] In response, the guard replied that the steamboat belonged to headquarters and consequently had been restricted from use by others. Harlan retorted that he only hoped to allow his men to rest on the lower decks beside the boilers so that they could dry their twice-soaked uniforms, but he was once more refused.

Harlan would not tolerate what he viewed as a great injustice. He called forward one of his most reliable captains, Frank Hill, and ordered him to see to the entry of his men aboard the boat. If the guards resisted, Hill was “to pitch them into the river.”[8]

Eager to finally be out of the weather, Hill promptly saw to his orders. He drew together a squad of soldiers and once more approached the plankway. The guard ordered them to halt, but the 10th Kentucky had prepared for his refusal. Hill ordered his squad to fix their bayonets and said to the guard, “Now, young man, I am going on that boat, and if you put yourself across my path, you will go into the river.”[9] Facing such determined opposition, the guard quietly stood aside as Hill ordered the advance onto the boat. For the rest of the night, the weary infantry finally slept in warm and dry conditions.

When morning arrived, however, Harlan began to consider what he had done. He recalled, “I began to turn over in my mind what had taken place, and learned that the boat was the Headquarters of Gen. Grant and that he was then actually in his room.”[10] Fearful of potential punishment for having forced his way past a guard, he quickly had his men vacate the steamboat. No punishment came from his actions, for according to Harlan’s telling the guards either did not report the trespassers or Grant himself chose to overlook it in recognition of “the extraordinary circumstances of the case.”[11]

Although certainly a fascinating tale, it is unlikely that Col. Harlan actually had his men force their way onto Grant’s headquarters steamboat, with the general sleeping aboard no less. Other accounts by the 10th Kentucky similarly recount Harlan organizing their embarkment aboard a steamboat against the will of the guards, but tellingly make no mention of the boat being Grant’s headquarter steamer Tigress, nor that Grant himself was aboard the vessel.[12]

Further undermining Harlan’s story is that Grant established his headquarters in a little log cabin on top of a hill in Pittsburg Landing.[13] In his post-war memoirs, Grant describes his failed attempts to sleep under a tree and in a log house serving as a hospital on the night of April 6, 1862.[14] This indicates that Grant chose to sleep on shore during his time in Pittsburg Landing for the battle, which is further confirmed by a staff officer who witnessed Grant doing so.[15] Taken together, both of these would point to Grant not sleeping aboard the steamboat boarded by the 10th Kentucky, or any steamboat at all, with him instead choosing to rest on land.

The final nail in the coffin of Harlan’s story as he told it can be found in that Tigress wasn’t even in Pittsburg Landing the night of April 7. It had instead been pressed into service to help transport the men and supplies of the Army of the Ohio as had occurred with Harlan’s own men earlier in the day.[16] Consequently, it couldn’t have been the lightly-manned vessel at rest that was so enticing to Harlan and his regiment.

Written almost a half-century after the events occurred, it seems likely that the aging Harlan might have been misremembering the details of his war service, or exaggerating for the eyes of his son, or perhaps even repeating a rumor he heard at the time. Given the number of steamboats in the vicinity and the similar recollections by his soldiers, there is no doubt that the 10th Kentucky under Harlan’s orders seized some steamboat. It is only his harrowing anecdote of narrowly avoiding the wrath of Ulysses S. Grant himself that crumbles under scrutiny.

Arie De Young has long been fascinated with the American Civil War, whether it is exploring battlefields, reading books, or attending roundtables. Currently attending Anderson University to achieve his bachelor’s degree, he plans to enter a doctorate program and academia. He has twice been a featured speaker at local Civil War roundtable events.

Endnotes:

[1] Loren P. Beth, John Marshall Harlan: The Last Whig Justice (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1992), 57.

[2] Peter S. Canellos, The Great Dissenter: The Story of John Marshall Harlan, America’s Judicial Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021), 139.

[3] Harlan to Richard Davenport Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers, Library of Congress.

[4] Harlan to Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers.

[5] Harlan to Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers.

[6] Harlan to Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers.

[7] Harlan to Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers.

[8] Harlan to Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers.

[9] Harlan to Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers.

[10] Harlan to Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers.

[11] Harlan to Harlan, 16-17 July 1911, Harlan Papers.

[12] Dennis W. Belcher, The 10th Kentucky Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War: A History and Roster (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2009), 29.

[13] Wiley Sword, Shiloh: Bloody April (Dayton: Morningside Bookshop, 1974), 349.

[14] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, ed. E.B. Long (De Capo Press, 1982), 181.

[15] Sword, Shiloh: Bloody April, 379.

[16] O. Edward Cunningham, Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862, ed. Gary D. Joiner and Timothy B. Smith (New York: Savas Beatie, 2007), 340.

“The older I get, the better I was.” [Lament of a veteran of the U.S. Navy.]

Although this researcher has never encountered this story before, it has the ring of truth. The Battle of Shiloh was a confused, edge-of-your seat conflict that had potential to end in favor of either side up until sunset on Day One (Sunday 6 April 1862). Buell’s Army began arriving at Pittsburg Landing from about 4:30pm and by Monday afternoon 7 April all but one of Buell’s divisions (that of George H. Thomas, which included the 10th Kentucky) had crossed the Tennessee River in time to participate in driving Beauregard’s Army of the Mississippi from the field. Meanwhile, there were thousands of wounded men that were retrieved from the battlefield, loaded aboard every available steamer and transported north to hospitals in St. Louis, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois and Ohio.

Major General Buell had strung a telegraph line from Louisville to Savannah Tennessee… but it did not cross the Tennessee River. A “picket boat” from Pittsburg Landing had to ferry official messages across the Tennessee River, connect to the end of the telegraph line, and return to Pittsburg Landing with official orders from St. Louis. Although “Tigress” was Grant’s floating HQ, it also acted as primary picket boat, relaying messages from Pittsburg Landing. The Federal gunboats “Lexington” and “Tyler” patrolled the river north and south of Pittsburg Landing. The only other “steamer detained at Pittsburg Landing” and not available for use as Hospital boat was “Iatan,” which acted as floating armoury packed with tons of artillery shells, small arms ammunition and powder. As steamers from St. Louis continued to arrive at Pittsburg Landing their newly reporting regiments were offloaded… and that steamer became available for use as Hospital boat. These vessels did not remain empty for long.

As for Major General Grant’s location: after riding aboard “Tigress” (commanded by Captain Perkins: see “The Conquest of the Missouri, being the Story of the Life and Exploits of Captain Grant Marsh” by Joseph Mills Hanson, 1909, pages 40- 47) from Savannah to Pittsburg Landing, arriving at about 9:15am Sunday, Grant was mostly in the field… returning briefly to Tigress at about 1- 1:30pm to query Captain Baxter (just returned aboard Tigress from Crump’s Landing) about “the orders delivered to Major General Lew Wallace.” While in conference with Baxter aboard Tigress, Major General Buell appeared on board Tigress before 2:30pm (Buell having “taken possession of a steamer” at Savannah for the ride to Pittsburg Landing.) Grant and Buell left the Tigress on Sunday afternoon. There is no record of either man returning to Tigress during 7 April or 8 April. On Tuesday 8 April Major General Grant was with Sherman in the morning and ordered “a reconnaissance” towards Corinth Mississippi in order to determine if the Rebels were truly retreating: the Battle of Fallen Timbers resulted, involving elements under command of Brigadier General Sherman against Rebel cavalry performing rearguard duties, under control of Brigadier General Breckinridge.

In summary: it is possible “an empty HQ boat/picket boat waiting at Pittsburg Landing was boarded on the evening of 7/8 April 1862 by elements of the 10th Kentucky under command of Colonel Harlin.” More information is required to determine if the incident really took place; and if so, what was the name of the steamer involved?

Great story. Mr Justice Harlan was a favorite jurist of my very senior and erudite professor of Constitutional Law.