Spindle Field’s Fall Haircut

Imagine my delight as I pop out of the woodline on the southern edge of Spotsylvania’s Spindle Field and I see row upon row of corn. It’s exactly what I should see at this time of year, but such has not been the case for most of the summer. The uncultivated part of this field, closest to the woodline, has been in dire need of a haircut.

That’s been the case all across the Spotsylvania Courthouse Battlefield. The open fields—unburned in the spring and mowed all summer—have become many deciduous jungles of fast-growing oaks and scraggly pines. Occasional tulip poplars, tall and stringy, have stretched their way in, and in some places, sumac has grown so thick, they look like short stands of palm trees thick enough to require a machete. Bristly thistles have started to show their purple globe blossoms.

But these were farm fields once here around Sarah Spindle’s farm. Elsewhere, the Landrums, the McCools, the Harrisons had farms of their own. Sarah Spindle’s farm field is mostly in cultivation these days, but the others are left as natural places.

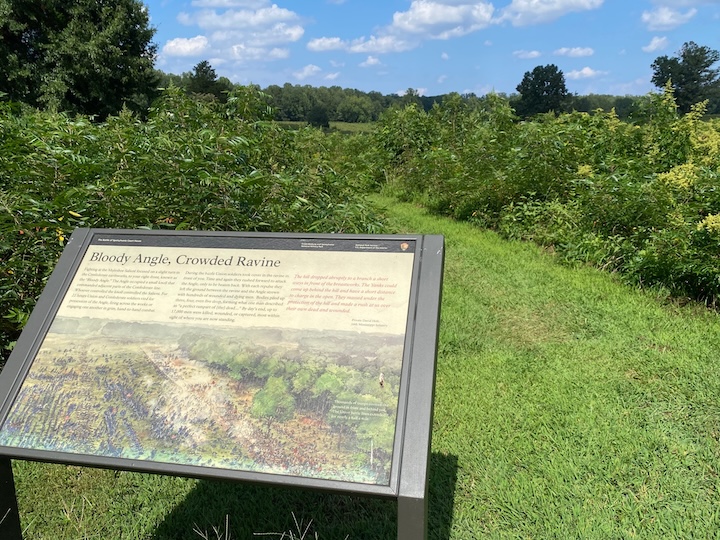

The challenge, of course, is that topography is such a vital part of the story of Spotsylvania Courthouse. The same can certainly be said on nearly any battlefield, but at a battlefield like Spotsylvania, where minimal interpretation and signage marks the field, being able to see the ground becomes especially important for understanding the story. When the foliage has taken over, land features get obscured and earthworks vanish.

In front of the Mule Shoe, the swale the did so much to direct troop movements into the maw of the Bloody Angle seems far less prominent, despite its sweep and size. The dueling earthworks along the Mule Shoe’s east face, where Federals and Confederates sniped at each other for twenty hours, dissolve into the terrain, obscuring the angry proximity of the lines. They have no power to illustrate, losing their most important value to us.

But the Park Service has been suffering budget cuts and staffing shortages. Mowing has tumbled down the priority list. And Spotsylvania, the least-visited of the park’s four battlefields, has always received less attention than the others because of its relative isolation.

But today I can see those rows of corn in the cultivated part of the field, no longer obscured by the wilder part of the field along the woodline.

What strikes me immediately is how they resemble rows of infantry. Imagine federal soldiers in Dennison’s Maryland Brigade lined up shoulder to shoulder in their advance at about 8:00 a.m. on May 8, 1864. I can’t see their point of departure on the far side of the field. A ridge cuts perpendicular across the field, obscuring its far side. When Federals reached the ridge, only then could they see another quarter of the field beyond and the confederate line at the far side along the woodline where I now stand.

That is something else the corn shows me today. Imagine those same Federal soldiers lined up in a long row, shoulder to shoulder, on the crest of that ridge line, silhouetted as easy targets for the waiting Confederates, who had only just rushed onto the field and perhaps hadn’t even had much time to get their bearings. Silhouettes on the ridge became easily recognizable targets for tired, disoriented veterans.

If I follow the walking trail down toward the corn, it intersects the ridge right next to Brock Road. Here, a bend in the road turns east toward the village, running along the upper lip of a large fishbowl in the landscape. Confederates used a rail fence along the road to help form a barricade against the first brigade-sized attack that crossed Spindle Field, six Federal regiments under the command of Peter Lyle.

For most of the summer, the fishbowl lay beneath a sea of foliage that seemed to fill the bowl. Now moved, the dramatic nature of the concavity shows. Lyle’s men got down into the fishbowl, many of his men in underneath the fire of the Confederates who could not depress their rifles far enough to hit them once the Federals got close enough. Lyle’s men ended up pinned against the lip of the fishbowl until finally flushed out by a flanking attack from Benjamin Humphrey’s Mississippians, who found it like shooting fish in a fishbowl.

Lyle’s men had no idea what they were marching into. From the perspective of their approach, a knoll hid the fishbowl in the same way that the ridge on the opposite side of the road hid the far woodline. The topography played tricks on everyone—tricks that have remained hidden this summer, buried beneath aggressive green.

Those of us in the preservation community talk about the value of “walking the ground” to better understand what happened there. But as this summer has illustrated, you have to be able to see the ground as you walk it.

I’m glad the Park Service has been able, finally, to mow. I’m sure for some folks, it seems like just another tedious chore that someone needs to do. But for those of us who know the ground and the stories it holds, a clear landscape makes a world of difference.

Great article, Chris! It’s amazing how much you miss if you just stick to the tour roads. The “good ground” plays an important part in battle tactics.

Thank you for this report, Chris!

Living essentially on a field of battle gives you such a grasp of the immediacy of the events. The men never leave…they are always there.

I wonder if this is the season for mowing because I’ve noticed a lot of “haircuts” in the Petersburg area, e.g. one can now see Fort Gregg (CSA) passing by on the road.

Your post about Spotsylvania provided an incentive to check the Revolutionary War Battlefield at Yorktown for “haircuts.” Alas, Yorktown rates a mixed review, and that has been the case for my thirty plus years of navigating the Encampment Loop. The open fields where our Continentals and French allies camped receive an obligatory “haircut” annually, and that signal event occurs a couple of weeks prior to the October Surrender Day celebration. On the other hand, the NPS Visitor Center, located within the British fortifications, receives regular attention in order to appease the sensibilities of our summer sunshine patriots. Unfortunately, Surrender Field, being a mile or so distant from the Visitor Center and beyond a line of sight, unfortunately warrants the annual “haircut” treatment. In my view, the very ground where “our independence was won” deserves more appropriate attention.

Thanks for this thoughtful and provocative piece. I’ll leave to others the historical arguments per se (I had ancestors on both sides), but my own experience tells me the following:

1. As a teacher of English, creative writing, and professional education (retiring in 2011 after forty years), I never had the above issues in my job description. Lucky me, right?

2. Maybe not so lucky: English literature, as taught in most public school, is a bit of everything, one of which is cultural history. You can’t teach it (well) without reading from the great African-American writers like Frederick Douglass to Zora Neal Hurston, Maya Angelou, Rita Dove, and beyond. And the C.W. itself generated a good bit of literature. And how are we to interpret the class-based, but race-conscious substrata under Kate Chopin’s Awakening? Luckily (or not), I could probe by acting as a devil’s advocate or even ask for What-Ifs like these: What if Walt Whitman, a poet and war reporter, had written a vignette to go in his Drum Taps collection, about an action involving the U.S. Colored Troops. Or write a postwar scene between Frederick Douglass and Robert E. Lee. Or what if Stephen Crane had lived long enough for a sequel to Red Badge? Write a scene in which The Youth Henry, an old veteran now, observes and reports on the trench-warfare horrors of WWI, or begins to teach in an integrated school. Write part of a spinoff of Their Eyes Were Watching God in which Tea Cake does survive and maybe goes on to the life of a civil rights activist or doesn’t. Write it from his point of view, or write a song composed by…. OK, you get the idea. Somebody should write a book about this.

3. As part of my ed. “backgrounds” course (in the 1990s), I had to deal with the cultural development of American education. You can’t avoid history there, but you could deal with it in generalities, trends, and so on, that address class, but don’t directly address race. At least that was not then explicitly in the curriculum. BUT I could differentiate and allow individuals or groups to get into those subjects. I could facilitate, which is my preferred stance anyhow.

4. My one recommendation, I guess, is that whatever we do, we must model reason, openness, fairness, curiosity, and imagination. There can be “no rank in the room” in those discussions. We are all learners.

5. Look at original sources, always.

6. Look for ways to use empirical evidence: E.g. Do searches on Google’s utility for occurrences over time in the public domain of certain terminology in certain contexts. I’m too old for this now, but many of us are not. There are dissertations to be found here. Language always matters!