The Issue of Transcription and Editing: Maintaining “Voice” and Authenticity while boosting Comprehension and Readability

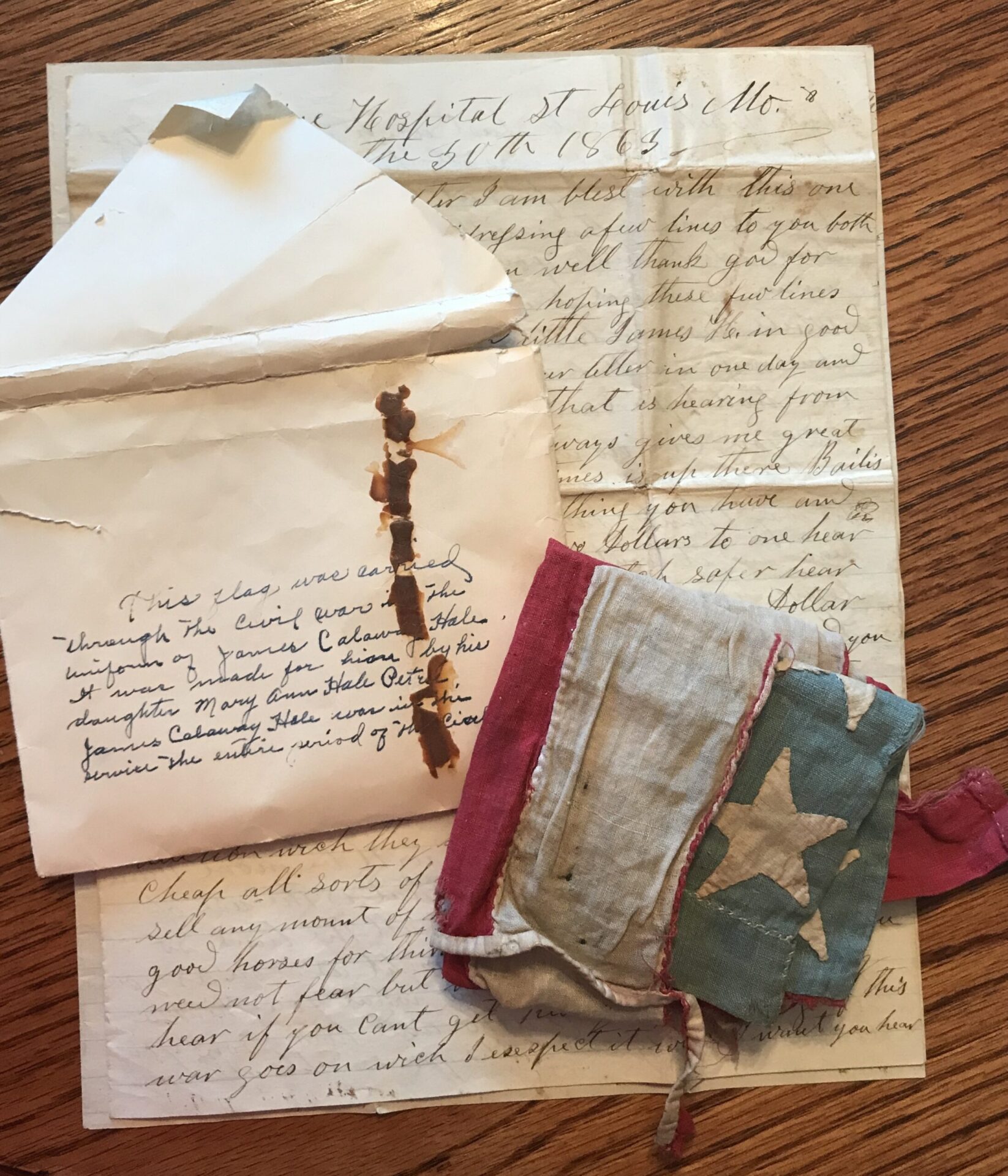

When a box of old family letters landed on my doorstep back in February 2023, the oldest dating back to 1846, I felt like I’d hit a winning jackpot. More than twenty years of researching my family history on Ancestry.com had led me to quite a few surprising connections and interesting stories about various ancestors, but never a treasure trove like this. That box eventually led me to write a book titled A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri, 1862-1865, which I wrote about in this earlier ECW post.

When a box of old family letters landed on my doorstep back in February 2023, the oldest dating back to 1846, I felt like I’d hit a winning jackpot. More than twenty years of researching my family history on Ancestry.com had led me to quite a few surprising connections and interesting stories about various ancestors, but never a treasure trove like this. That box eventually led me to write a book titled A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri, 1862-1865, which I wrote about in this earlier ECW post.

Initially, though, I merely set out to transcribe the letters to learn more about my family’s history. While fifty of those letters were from the Civil War, there were others from the Oregon Trail, early California, and between various family members in Missouri and Tennessee, with several from the 1850’s and the most recent written in the early 1900’s.

If you’ve ever tried to read old letters or other historical documents, you know that the writing can often be quite difficult to read. All of the letters were written in cursive, often using older writing forms (such as “fs” instead of “ss”), and most had absolutely no punctuation or paragraphing. Some letters had pieces of them missing, especially the Civil War letters – I’m not sure if that was a censorship issue or if the letters just got torn over the years.

Some letter writers had neat handwriting and almost perfect spelling (such as Benjamin Petree); others had messier writing, left words out, and had very “creative” ways of spelling certain words, such as “bocay” for “bouquet” and “persipick otion” for “Pacific Ocean” (those two definitely made me laugh). This was especially true of the letters written by Jane Kennedy Hale from the “Nebraskey Terytory” along the Oregon Trail.

James Hale’s writing was fortunately quite neat, but he did have some “creative spellings” and also frequently used slang I’d never heard before. I quickly adjusted to his use of “the seecesh” to describe the secessionists he was fighting, but when he talked about “taking a french,” it took some research to figure out that a “french furlough” meant someone had deserted or taken an absence without leave to go home for the holidays.

At times, due to Hale’s lack of punctuation, it was hard to know whether certain phrases were situated at the end of one sentence or the beginning of another. His use of capitalization was haphazard at best. His distinct dialect certainly came through as well, but that was at times rather charming. In one particular letter from Helena Arkansas, from which I share an excerpt later, I couldn’t help being reminded of Mark Twain’s use of dialect in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

So, once I decided to compile these letters into a book, how did I decide to handle some of these “ethical” issues? Fortunately, as a long-time high school teacher, I’d had plenty of practice reading misspellings and messy handwriting, so I was able to painstakingly work my way through the letters fairly well, though often requiring a magnifying glass. There were, however, places I’d get stuck, unable to make out a name or word or phrase no matter how many ways I looked at it.

Sometimes these questions resolved themselves because the same word would appear later, written more legibly. Such was the case when I thought Hale asked his wife how the “frogs” were coming along (which confused me), then later realized he had written “hogs” (which made so much more sense). In the case of some of the names, I was greatly helped by Andrew County Historical Society Genealogist Kathy Ridge (I wrote about her in this previous ECW post). She recognized many of the names and was able to correct my misreadings or Hale’s misspellings on several occasions. Even better, she was often able to tell me something about that person’s history, for many of the names mentioned came from Andrew County.

There were several other questions I had to deal with as I began putting the letters into the book. First off, how much should I correct the spelling for the sake of readability? Should I add proper punctuation and capitalization? And if a word was missing, should I add it in brackets or just leave it out? If there was slang, should I try to explain it in the text of the book or save that for the endnotes? How should I handle all the names – especially of unknown figures – who came up? And finally, how could I maintain Hale’s “voice” while still making the letters easier for readers to follow?

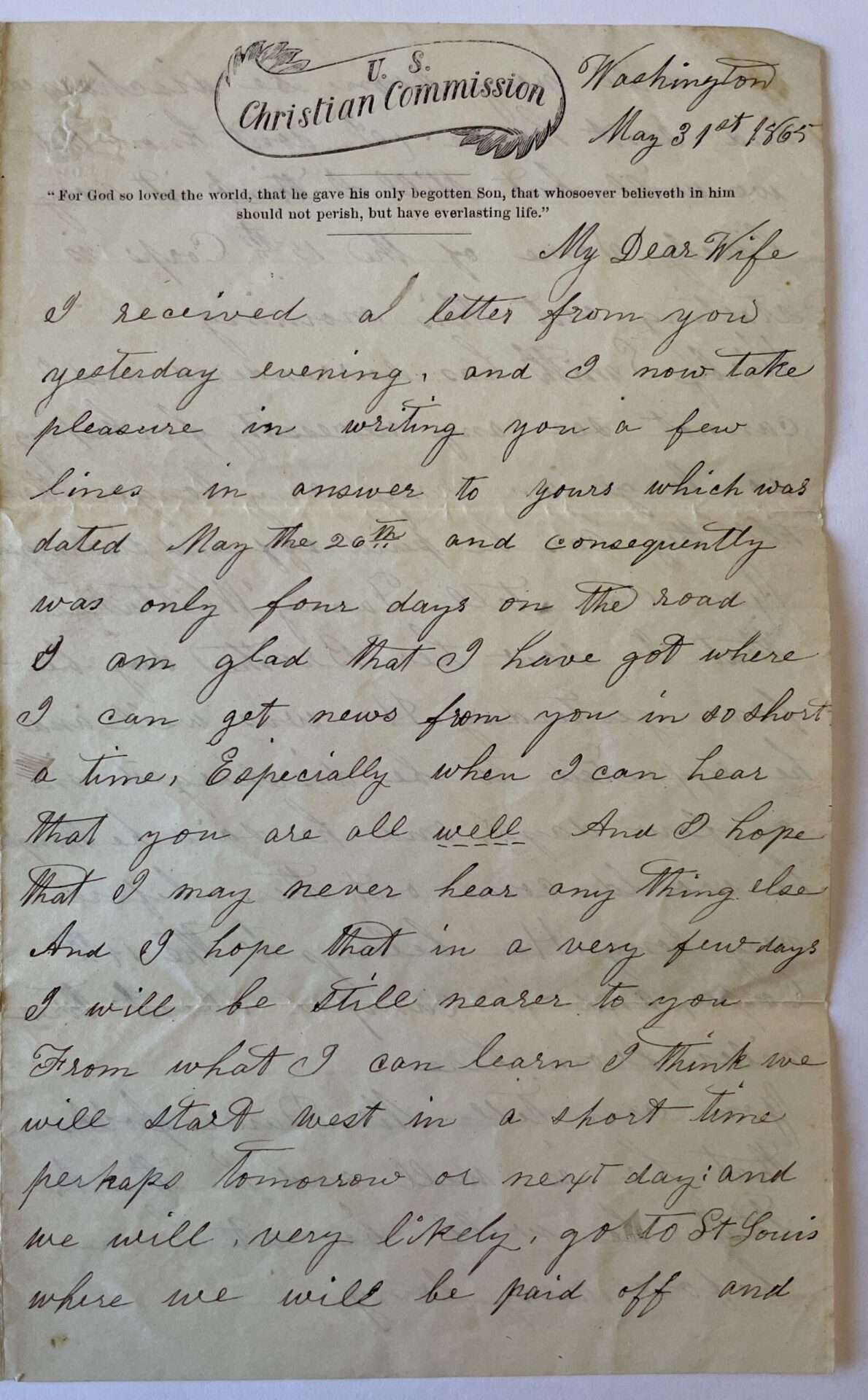

As I explain in the Introduction to my book, “In my letter transcriptions, I tried to keep the original word choice as much as possible in order to maintain each author’s voice, but in many cases I corrected spelling errors and added punctuation to make reading easier.” One way I maintained Hale’s voice was by keeping his continuous use of “They is” instead of “There is” at the start of his sentences. Spelling, however, I often corrected, and I added punctuation and capitalization where it seemed appropriate. Here’s an example from one page of a letter Hale wrote from Helena, Arkansas, sometime in February 1863. First, you can see the letter exactly as James Hale wrote it (italicized); then after, as I edited it for the book:

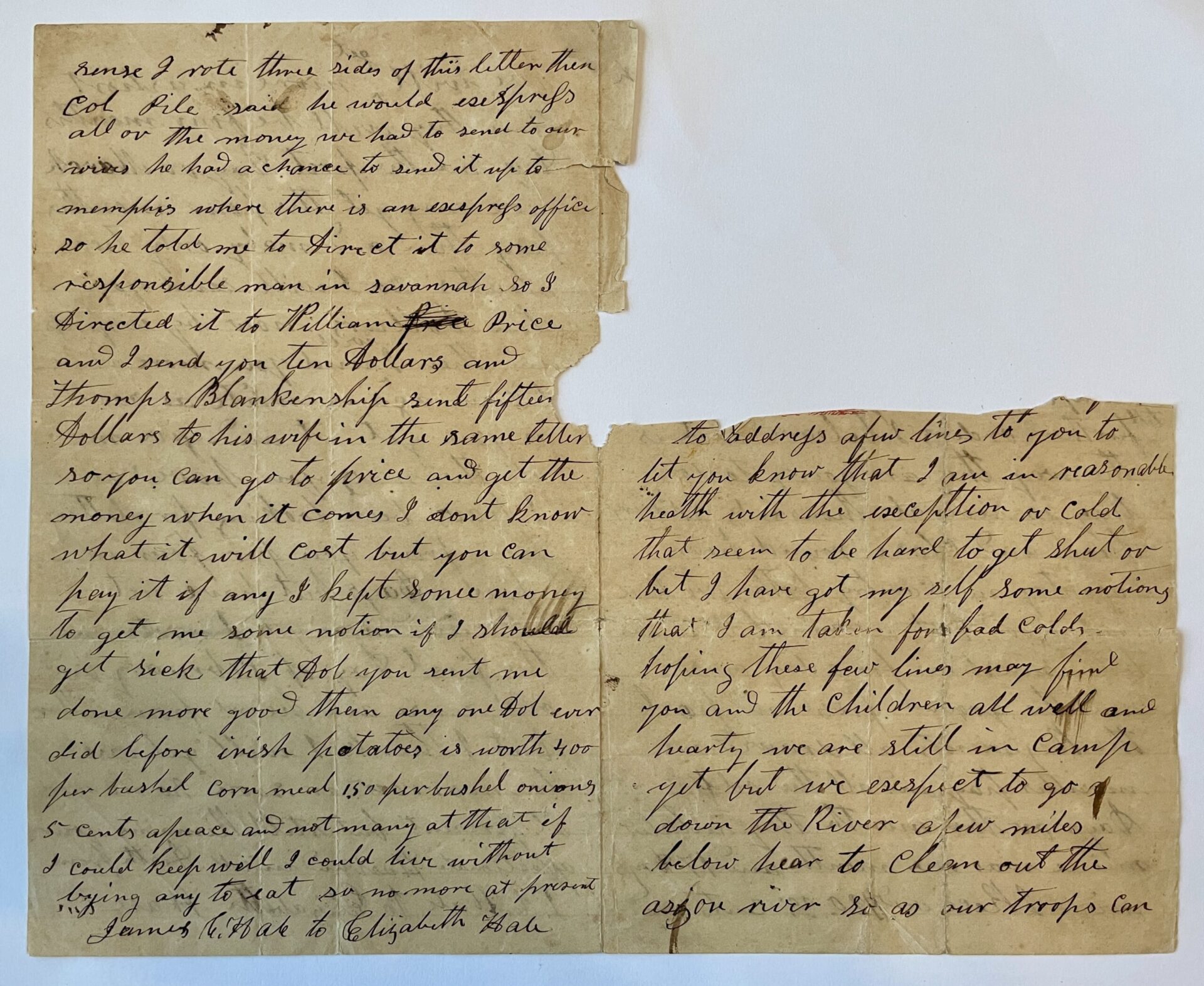

Sense I rote three sides of this letter then Col. Pile said he would exsprefs all ov the money we had to send to our wives he had a chance to send it up to memphis where there is an exsprefs office so he told me to direct it to some responsible man in savannah so I directed it to William Price and I send you ten dollars and Thomfs Blankenship sent fifteen dollars to his wife in the same letter so you can go to price and get the money when it comes I don’t know what it will cost but you can pay it if any I kept some money to get me some notion if I should get sick that Dol you sent me done more good that any one Dol ever did before

Since I wrote three sides of this letter, then Col. Pile said he would express all of the money we had to send to our wives. He had a chance to send it up to Memphis where there is an express office, so he told me to direct it to some responsible man in Savannah, so I directed it to William Price (7), and I sent you ten dollars, and Thomas Blankenship sent fifteen dollars to his wife in the same letter. So, you can go to Price and get the money when it comes. I don’t know what it will cost, but you can pay it if any. I kept some money to get me some notion [medicine] if I should get sick. That dollar you sent me done more good than any one dollar ever did before.

In my edited versiion, you can see I kept some of Hale’s “voice” despite its incorrect grammar by today’s standards, but I added punctuation and capitalization and fixed some of the spelling issues. I also added an endnote (7) to provide more information about the “responsible” William Price, but I did not try to explain who Thomas Blankenship was since I had no additional information about him. Price, as I learned from Genealogist Kathy Ridge, was a respected Savannah merchant, and Savannah named one of its streets after him. I also clarified that “notion” referred to “medicine” by putting the latter in brackets.

I must admit, I had a difficult time making out the word “Dol” for quite a while until I finally realized that was how Hale abbreviated “dollar.” Then, his words made sense: he was grateful to his wife for the dollar she sent because it allowed him to purchase the medicine he needed. He suffered a lot from illness while in Helena, and many soldiers died there due to the unhealthy conditions. Hale ended up being transferred to the General Hospital in St. Louis at the end of June 1863 due to his dysentery and rheumatism.

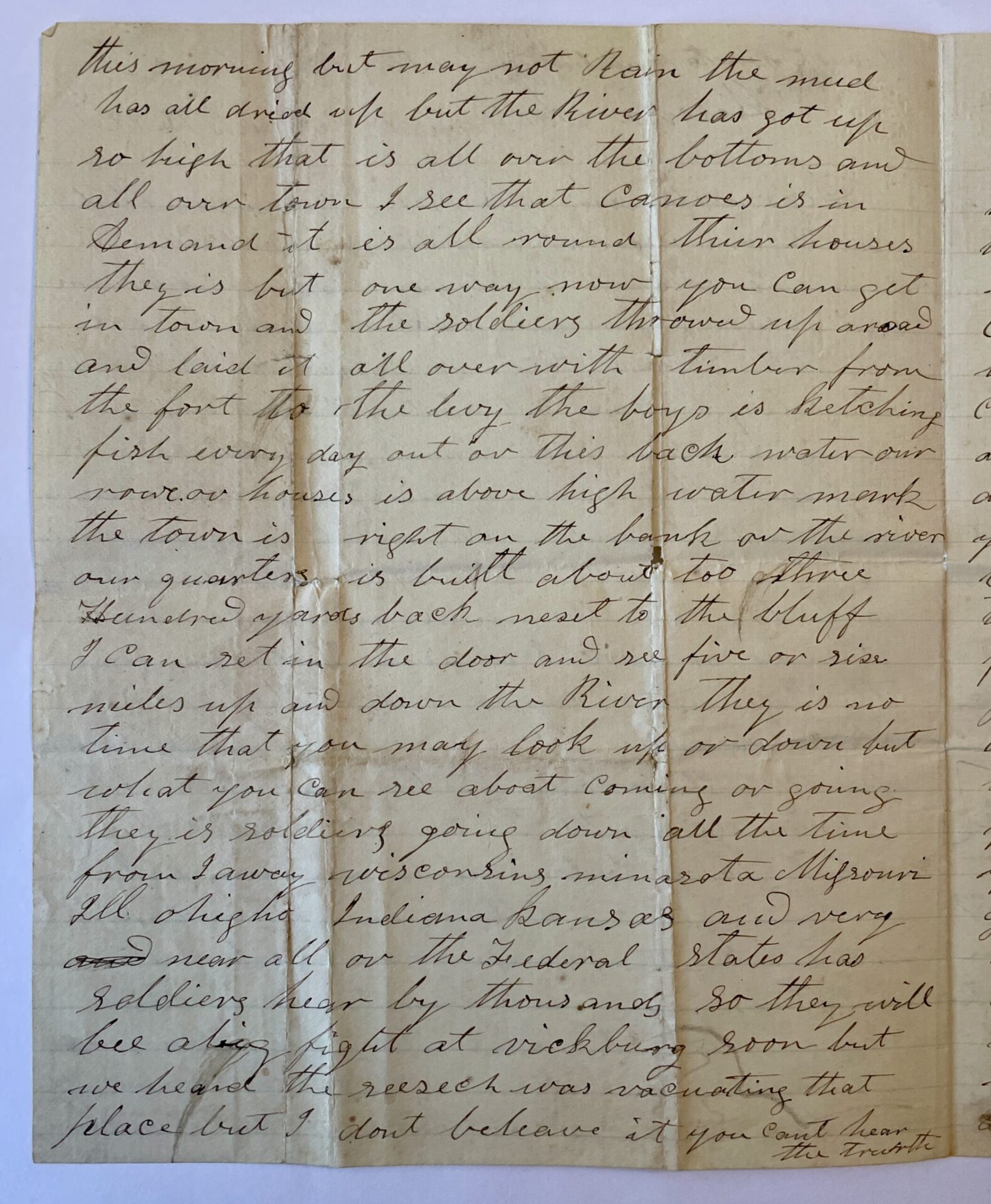

Here’s another example, this one from a letter dated March 22, 1863, showing Hale’s original writing (italicized), then my edited version:

I bought myself ahigh pare of boots the other day water proof so as I could wade deep mud but has cleard off and have not rained for over aweek but it is cloudy this morning and may not rain the mud has all dried up but the River has got up so high that it is all over the bottoms and all over town I see that canoes is in demand it is all round their houses they is but one way now you can get in town and the soldiers throwed up around and laid it all over with timber from the fort to the levy the boys is ketching fish every day out ov this back water our row ov houses is above high water mark the town is right on the bank ov the river our quarters is built about too three hundred yards back next to the bluff I can set in the door and see five or six miles up and down the River they is no time that you may look up or down but what you can see aboat coming or going they is soldiers going down all the time from Iaway wisconsins minasota Mifsouri Ill ohigho Indiana kansas and very near all over the Federal States has soldiers hear by thousands so they will be a big fight at Vickburg soon but we heard the seesech was vacuating that place but I don’t beleave it you can’t hear the truth.

I bought myself a high pair of boots the other day – water proof – so as I could wade deep mud, but it has cleared off and has not rained for over a week. The mud has all dried up, but the River has got up so high that it is all over the bottoms and all over town. I see that canoes is in demand. It is all round the people’s houses. They is but one way now you can get in town, and the soldiers laid timber all over town from the fort to the levy.

The boys is catching fish every day out of this back water. The town is right up on the bank of the river. Our quarters is built about two or three hundred yards back next to the bluff, above highwater mark. I can set in the door and see five or six miles up and down the River. They is no time that you may look up or down that you cannot see people coming or going. They is soldiers going down all the time from Ioway, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Kansas, and very near all over the Federal States – soldiers here by the thousands. They will be a big fight at Vicksburg soon. We heard the Seesech will be evacuating that place, but I don’t believe it. You can’t hear the truth.

As you can see, I didn’t always correct Hale’s grammar. I thought it was important to hear his voice when he was clearly understandable. Sometimes, that voice was so striking, I made very few changes other than adding punctuation. Here’s a perfect example of that from Hale’s March 29, 1863, letter from Helena:

I was going down to the river the other day, and they was a lady and her daughter come out on the porch trying to get a long plank from the top of the porch to the road, water all round the house, so I took a hold of one end of the plank and raised up on the edge of the road so as they could walk out. Says I to the old lady, I would not like to live here. Why, says she. Says I, everybody will die with sickness here after a while. Says she, it is always heaps healthier after an overflow than if they was none. It cleans everything off, says she.

It was this particular passage that reminded me of Mark Twain’s writing – so picturesque!

I hope the above explanations and examples give you a bit of insight into some of the “ethical issues” I faced while transcribing and editing Hale’s letters. Perhaps at times I edited too much – but I did what I thought would aid both comprehension and readability. If you haven’t already, I encourage you to check out the rest of Hale and Petree’s letters in A State Divided, which is available at this link.