Coming to Terms with My Civil War Era Family History

I am fortunate to know a great deal about my family’s history, a knowledge set I am excited to use as a lens into the history of the United States with my students. I feel it provides a tangible connection for students to see that history is made not by great figures, but by average people living their lives as best they can.

I am fortunate to know a great deal about my family’s history, a knowledge set I am excited to use as a lens into the history of the United States with my students. I feel it provides a tangible connection for students to see that history is made not by great figures, but by average people living their lives as best they can.

That family history is spread wide. Within the first weeks of my early US History course, I show students burial records of my ancestor, Jacques, who arrived in New Orleans in 1721 and was laid to rest in the city’s first cemetery. I talk about how Jacques’s grandson Zenon filed a land claim following the War of 1812 because he claimed to be part of the Louisiana militia call-up by Andrew Jackson. I talk about how both of my grandfathers, Lamie and Charles, served in World War Two, one in the army and the other in the navy, and how my uncles served in Vietnam. I talk about a distant cousin who had a ship named in his honor in World War Two and am fortunate to be able to show them copies of the ship’s logbooks. These are just a small few of a host of other examples ranging from 1721 to today.

I also talk about my family’s time during the Antebellum period and Civil War era. After coming to Louisiana, the Chatelain family settled in Avoyelles Parish, near Marksville and Mansura. There are still many Chatelains there today. I tell my students that this was the area that Solmon Northup spent most his dozen years enslaved, and that my family lived mere miles from where Northup labored, something that provides a personal touch to complement their reading of Northup’s memoir. Then we talk about how ten Chatelains fought in the Civil War, all for the Confederacy in Louisiana infantry and cavalry regiments. Most survived the war, though not all.

The question comes up every semester. If my family lived where Northup was enslaved, and if the Chatelain family fought for the Confederacy, did they actively participate in enslaving anyone? My great grandfather, in the early 20th century, was a poor sharecropper who grew sweet potatoes, and my grandfather, who only learned English in school, moved to New Orleans (the big city!) to escape that life. The family’s history followed that avenue of poor farmers just trying to get by. I also looked up a book of Louisiana enslavers and found no Chatelain entries. So, each semester I confidently informed my students that yes, the Chatelain family fought for the Confederacy, but had no part directly in enslaving anyone as they were too poor.

This past summer I found out just how wrong that claim was.

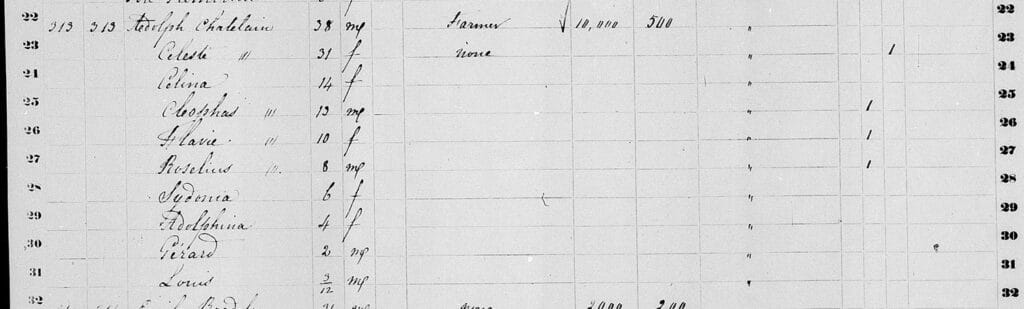

I spent much of summer 2025 digging through census records for some ongoing projects. During that research, I took the time to dive into my family’s census records as well. My great-great-great-grandfather was named Adolph Chatelain (not to be confused with relatives Adolph Z. Chatelain or A. Chatelain, both of whom fought in the Civil War). The 1860 census lists him as 38 years old, living with his wife Celeste, and eight children (ages ranging from 14 years old to 3 months old at the time of the census). Then I noticed something interesting. The family had accumulated wealth estimated at $10,500.

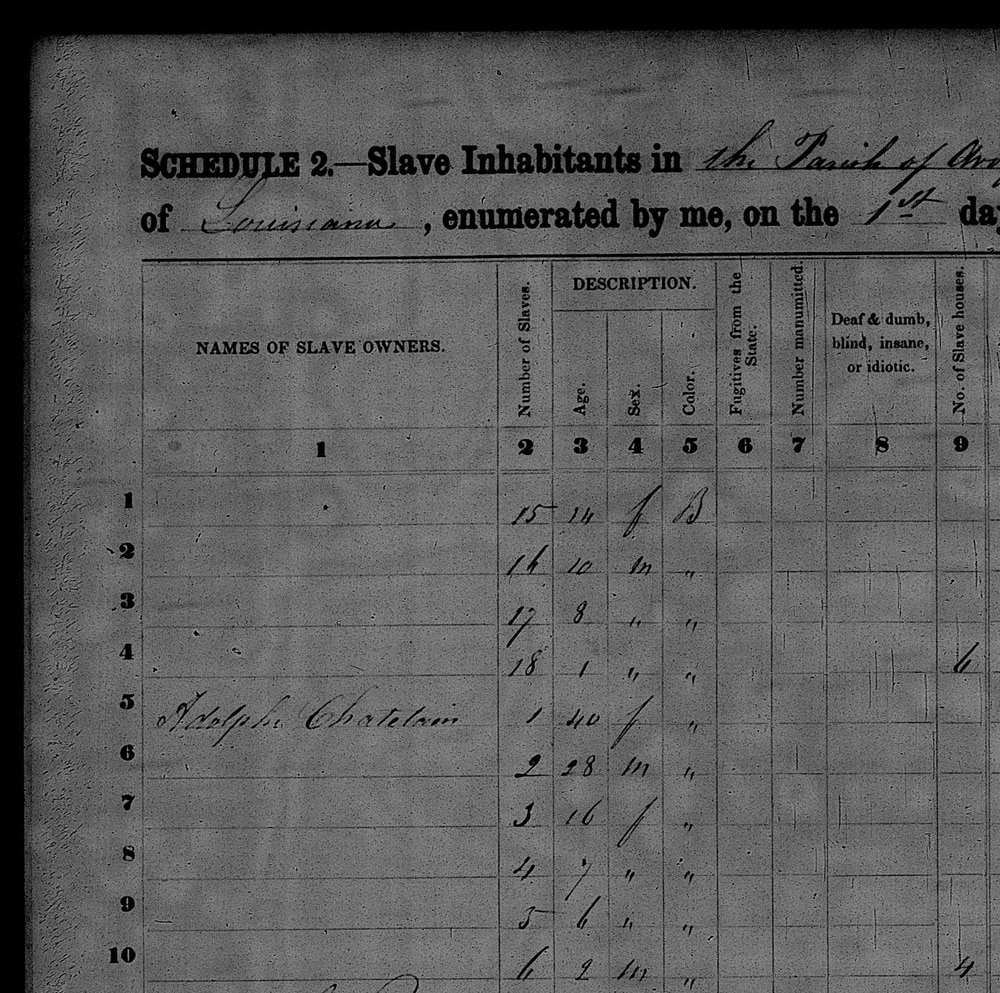

I kept digging, on a hunch, and found the Avoyelles Parish Slave Schedule for the 1860 Census. It did not take long to learn the truth. Adolph Chatelain owned and enslaved six people. I do not know their names, and at this point the only real information I have are their basic descriptions from the census: a 40-year-old woman, a 28-year-old man, a 16-year-old girl, a 7-year-old girl, a 6-year-old girl, and a 2-year-old boy. I cross-referenced this with the 1850 Census, which listed Adolph Chatelain as owning only one enslaved person: a 17-year-old boy (likely the same 28-year-old from the 1860 Census).

So, in this instance, our family’s lore was quite off, and it made me ponder a great deal. Adolph owning these people was not my fault, but because of this information I felt a weight upon me. There was an element of shame and disappointment at what my family had once been a part of, but I also felt a sense of responsibility in ensuring I freely acknowledged my family’s past actions. More so, I found this out literally just a couple of weeks after repeating the same statements about my family not being wealthy enough to enslave anyone to my summer classes.

As I returned to campus to prepare for the fall semester, I took some time to speak with a fellow faculty member about what I learned this summer. The two of us pondered the weight of family legacies and reflected on the greatness of being able to look at all these original documents, often with just the touch of our fingers from the comfort of our homes.

When the fall semester began, I started teaching several classes of Early US History again, one class of Modern US History, and a class on Early World Civilizations. The modern history course starts in 1877, and I generally spend the first class re-exploring briefly emancipation and Reconstruction, tying it all to racial relations up to the year 1900. This semester, that class is packed with students who previously took my Early US History course, and the same recurring issue came up in my mind.

I felt a responsibility to ensure these students heard the truth from me. So, when our first class began, I started by announcing that I had some newly discovered family history to share. Most of the class leaned forward in anticipation, and I came out and admitted it: In 1860, my great-great-great-grandfather owned six people.

I teach in suburban Houston. The vast majority of my students are black and brown. At first several of them had looks of disgust, recognizing exactly what I was saying. Then very quickly their facial expressions changed to ones of inquisitiveness, interest, and even understanding. They took great interest in copies of the census records I passed around.

We had a frank discussion about why I brought this up to them. For one, I learned something new and felt they should know, since we previously discussed it, as I felt an ethical responsibility to set the record straight. Besides that, this facilitated a deeper conversation about what family history means, and who bears the weight of past historical events. It also allowed a discussion about the importance of going to the original source material, and about historical revisionism, and how this term that often holds a political spin is simply reassessing our understanding of the past with new information to create a more complete interpretation of that past. Finally, this has paid dividends already, as students in that class have begun sharing their own thoughts, opinions, and ideas – even controversial ones – with the rest of the class. By sharing how members of my family had previously enslaved people, I fostered a safer class environment for others to share things they might have previously thought too controversial.

My students did not hold me personally accountable for the actions of my ancestors (or at least that is the impression I had). They did not think of me as a lesser person, just as I do not hold the actions of my ancestors as a personal weight to bear. In class, I had previously admitted some pretty cool things my family had done, and now I was freely admitting how my family also had scars in the past. From what I could tell, they all appreciated I was willing to even speak about such tough subjects.

This one anecdote hopefully impacted how these few dozen students view the past and how they explore how people today must reckon with past events. We do not bear the weight of being personally responsible for events from before our births, but the scars of those events remain, and a good step to healing wounds is having open conversations about what caused those scars in the first place, why they matter, and what has been done since then. My students handled this tough conversation with clarity, understanding, acknowledgement, inquisitiveness, and a calm demeanor that fostered better engagement with the information and documents we explored together. We could all learn much from them.

You are responsible for nothing, absolutely nothing and should apologize for nothing. Your obligation is to your direct blood line relatives and remembering them as such. You have perpetuated the myth of transference. You should look further to

understand them. But not self flagellate.

Neil, what is this “pondering the weight of family responsibility ‘ nonsense? You know as well as I do that in Louisiana’s complex pre-war class and race structure that there were a multitude of freed people of color who owned slaves. Think their descendants are wandering about like Eeyore pondering issues like this? What are you going to unburden next, having a relative who participated in the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre? One who poured the oil on Jean D’arc’s wood? It was what it was, now it’s gone. Thank God. We are not our ancestors. There is more than a large cottage industry that derives it’s modern existence from self flagellation or, alternatively , “you owe me” ism. Both are economically and socially worthless. Or, if not, sign me up for some Anglican Restitution for what they did to my local parish after the Battle of the Boyne.

I agree with both responses about our responsibilities for what happened in our family’s past, past history. Unless you have the keys to a Delorean, there is absolutely nothing you can do about it.

P.S. if you own a Delorean, make sure it is equipped with a flux capacitor!

The desire to discover one’s roots, the pride in the struggle and accomplishments of your ancestors, the effort to preserve history and its artifacts, and bragging about the various great great great granddads’ service in the Civil War. People go on and on about the importance of knowing history. But soon as they come up against how awful most people can be, its ho hum it doesn’t mean a thing.

My only direct ancestor who lived in the United States during the Civil War was a farmer in Ohio, and I was disappointed to learn he apparently never volunteered to fight. But you can’t control what someone did or didn’t do 160 years ago, let alone today.

One of the dangers of researching Family Ancestry: finding one or more relatives who did not “meet expectations” of the present day. Some of us feel uncomfortable when we encounter period photographs of relatives smoking; some are disappointed to discover ancestors with jail time. In my case, a direct descendant was recorded as “Died as result of a cow stepping on his foot.” Upon further investigation, this man was found to have committed suicide. I have one Civil War ancestor who “mustered out when his regiment disbanded January 1866” …but he was never seen again. A cenotaph in Iowa records his death as taking place January 1866. I want to know… and yet I don’t want to know. For the time being I am leaving Corporal McKinnis to rest in peace.

We cannot change the past. Each of us is doing his or her best to be our best today.

The uniqueness of our connection to our ancestors makes it entirely understandable that we may feel a “personal weight of responsibility” upon learning that they owned slaves. That has certainly been my experience, and it seems to me a natural reaction. Coming to grips with that reality is a real learning experience (to say the least) and, for me, it has led to more empathy for the suffering and perseverance of African Americans.

Ummm…. you are the historian, so you must know many former slaves looked on their slave days with some fondness. Many former slaves reported to the Federal Writers Project in the 1930s that they had decent or even kind owners. None of that excuses slavery. Nothing can. And much of that fondness, it seems to me, is based on the relative material comfort they experienced before and after slavery. Post-slavery times were super harsh for former slaves. But, you could lighten your load a bit. Unless you can speak to how your ancestors actually treated their slaves, you have no idea what those six slaves experienced.

Tom

They experienced dehumanization in the most literal sense. Every day they experienced fear of family separation and physical or sexual violence based on the whim of their enslaver or market conditions over which they had no agency. The slave narratives from the Federal Writers Project are generally considered less than reliable source material given the elapsed time and (more importantly) the context of Jim Crow that loomed over the interviews.

Correct. Slavery was wrong in all respects. But, that is not the same as saying it conveyed no benefit as perceived by the enslaved themselves. Read the narratives. They are consistent in many respects. Discounting living witnesses to the institution of slavery should require some care.

Tom

I can’t believe that I have to explain this to anyone in 2025, let alone someone who is obviously interested in the subject. I’d encourage you to read the autobiographies of Frederick Douglass or Josiah Henson, then read “Twelve Years a Slave” by Solomon Northrup. Finally try read (if you can stomach it) Harriet Jacob’s “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.” Once you are done with all those, you can tell me about all these alleged benefits of being enslaved. I’m rather fond of Abraham Lincoln’s quip, “Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery, I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.”

Re-read my posts. Nowhere do they “argue for slavery.” Sigh. I can trade you books that suggest slavery was not without benefit for every book you cite that it had zero benefit. Thanks anyway.

Tom

Eloquent, honest, and well written. Thanks for sharing, good work.

This is a great post. I have never understood the perceived need for somebody living in 2025 to “defend” or align themselves with everything their ancestors believed or did. My ancestor served three years in the Army of the Potomac. He was a product of his time and place. He believed some things that I, too, believe. He had other beliefs that I do not share, some of which I think were simply wrong. One thing I am pretty certain of, however – if he saw me mindlessly defending or agreeing with everything he believed 160 years later, he’d likely be embarrassed to call me a descendant. I won’t mention a more distant ancestor who may (key word) have been involved in clandestinely selling gunpowder from the local minute man supply. LOL