“Rally, Boys, Rally”: Captain Hugh Irish and the Battle of Antietam

ECW welcomes back guest author Danny Brennan.

On the morning of September 17, 1903, hundreds of visitors gathered near Sharpsburg, Maryland, which forty-one years earlier became the site of America’s bloodiest day. But this time, the crowds didn’t come to fight. They came to unveil a monument honoring New Jersey troops who fought at the Battle of Antietam.

President Theodore Roosevelt addressed the crowd, which included an estimated 304 veterans.[1] Among them was Ezra Carman, the former colonel of the 13th New Jersey Infantry, who spent much of his career preserving and interpreting the surrounding battlefield. But it wasn’t a politician or soldier who unveiled the monument. That honor went to Mrs. J. Hartwell, sister of the highest-ranking New Jersey soldier killed at Antietam: Capt. Hugh Irish. As a band played and a salute rang out, she pulled away a large flag, unveiling a 40-foot monument topped by a statue of her late brother.[2]

The monument commissioners chose Capt. Irish not only for his rank, but for his character—his leadership, courage, and warm demeanor. Born on August 10, 1832, in Victory Township, New York, Irish lost his father at age thirteen and soon became a printing apprentice for the Paterson Guardian in New Jersey. That job led him back to New York as a master printer, where he married Elizabeth “Betsy” Haight, in 1854.

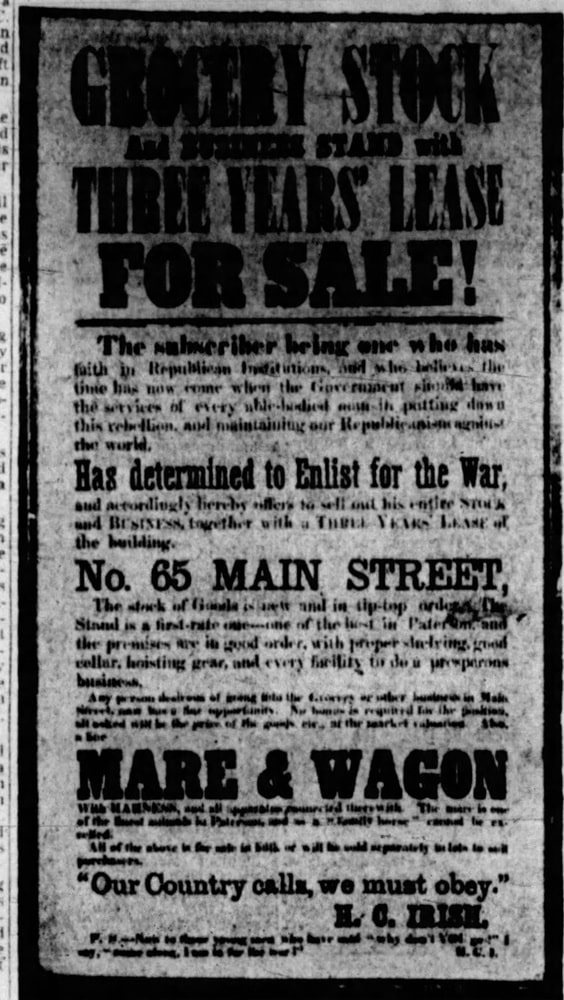

Irish returned to Paterson two years later to become editor of the Guardian, a beacon for the budding Republican Party.[3] As civil war loomed, he used his platform to support the Lincoln administration. Irish eventually stepped away from printing to open a grocery store, which provided him a venue to transform patriotic words into action when the president called for 300,000 more volunteers in the summer of 1862.

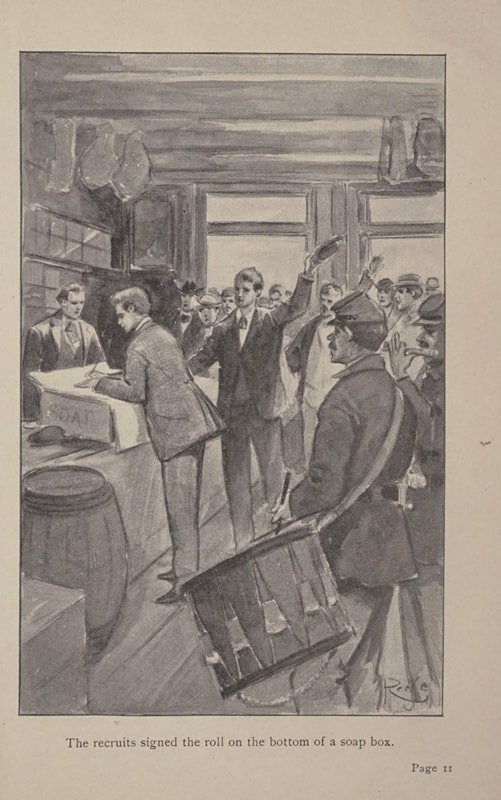

Though he left behind a pregnant wife and two sons, Irish decided that patriotism outweighed personal ties. He stressed in an advertisement selling his store how he committed himself to “putting down this rebellion and maintaining our Republicanism against the world.”[4] He soon began raising Company K of the 13th New Jersey Infantry, one recruit recalling how Irish’s “grocery store was transformed into a recruiting office…[where] the recruits signed the roll on the bottom of a soap box.”[5]

The 13th New Jersey left home in late August after minimal training, led by the experienced Col. Ezra Carman. Meanwhile, the Union was going through what regimental historian Samuel Toombs described as “the most critical period of the war.”[6] Confederate forces crushed Federal troops at Second Bull Run, emboldening Robert E. Lee to invade Maryland. George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac needed to react quickly, and they did so by calling on brand-new regiments.

The XII Corps, weakened from heavy casualties suffered at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, doubled its strength by welcoming five new regiments. The 13th New Jersey was one of these, placed in Gen. George H. Gordon’s veteran brigade on September 9. The subsequent march into Maryland was grueling, particularly for the green soldiers. Crowell remembered how Capt. Irish looked after his sunstruck and footsore soldiers, causing him to be “beloved as a father by the men.”[7] Those who persevered crossed Antietam Creek in the early morning of September 17.

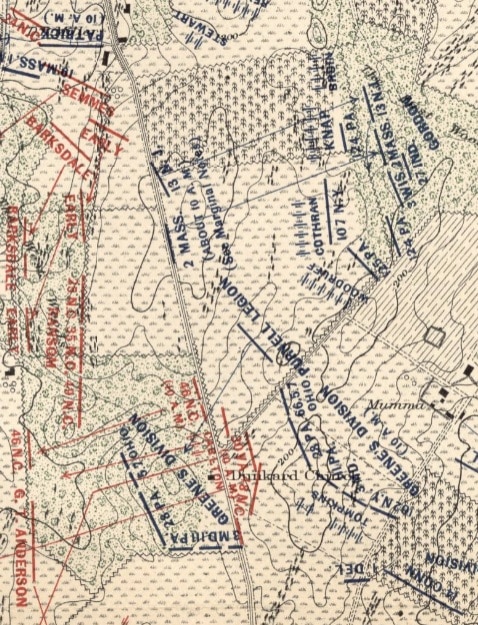

The New Jerseyans spent much of the day’s battle positioned in the East Woods. Irish waited anxiously, predicting to a sergeant, “I will never come out alive.”[8] The inexperienced bluecoats soon heard the shots of Confederates surprising a large U.S. force in the West Woods, about a half mile away. Gordon’s brigade was ordered to counter the attack. Their brigadier directed two regiments to advance first: the 2nd Massachusetts on the left and the 13th New Jersey on the right. It was around 10 a.m. when the soldiers advanced westward.

The men jogged into Miller’s Cornfield. The remaining corn stalks, coupled with littered bodies and supplies, turned the untrained men into a mob. For much of their advance, groans of the fallen joined with the whiz of bullets and the crash of distant artillery. Irish’s Company K on the right end of the line reached the pike first and began crossing the road’s eastern fence. Shots soon came from the woods 150 yards away.[9] Colonel Carman reported that he then “formed my line and prepared to dispute the advance of the foe.”[10]

Whatever semblance of order the officers created disintegrated when a blue-clad man came from the West Woods, insisting that the Federals were firing on their own men. A momentary ceasefire from the New Jerseyans was greeted with an enemy volley. The men’s lack of training caused some to fire back while others fled. Most paused in confusion.

Amid the chaos, Capt. Irish urged his men forward. He crossed over the pike’s western fence, raised his sword, and shouted, “Rally, Boys, Rally!” Then, a bullet found its mark through his chest. Sergeant Herber Wells rushed over to his captain. “Herber, I am killed,” was all Irish could get out before he expired. The mortal wound “left a small red spot, but which shed no blood.”[11]

Irish’s death shattered the regiment’s resolve. Private Sebastian Duncan implied that Irish’s push was a solitary event, for soon after, “some of the officers who had driven us in [were] now leading us out.”[12] The 13th left the 2nd Massachusetts unsupported as they retreated to the East Woods. Though the unit later occupied the West Woods, they were pushed back around noon. For the New Jerseyans, Antietam was a brutal initiation into the realities of war.

When the regiment retreated, Sergeant Wells remained with Irish’s body despite a “perilous” crossfire. He gathered the captain’s watch, diary, letters, and sword before rallying three others to retrieve Irish’s body. Though they moved Irish away from the pike, they could not remove him to the East Woods. Wells feared for his commander’s remains into the next day but felt some comfort from a rumor that “the surgeon has taken steps to secure his body.”[13]

The 30-year-old captain was interred on the crimsoned ground east of where he fell, the location marked by a “rudely carved” headboard.[14] Weeks later, his body returned to Paterson. A hearse inscribed with the words “Rally, Boys, Rally” carried him to his funeral service and burial in a local Baptist cemetery.[15] Betsy Irish was devastated. In a letter thanking Wells for returning her husband’s belongings, she wrote, “I can’t feel that I have much to live for.” Her strength ultimately gave out on February 25, 1863.[16]

Captain Irish may have served only briefly, but his legacy endured. Members of the 13th New Jersey, hardened by three years of combat experience after their baptism of fire at Antietam, remembered Irish as “the first to fall,” even though others fell earlier on the advance to the Hagerstown Pike. A Sons of Union Veterans post took on his name and remained active until the late 20th century. And in 1903, Irish’s sister unveiled his likeness that topped the monument honoring all New Jersey soldiers who fought at Antietam.[17]

Born in a township called Victory, Capt. Irish fell at the height of an ill-fated attack. But his efforts, along with the efforts of many other soldiers around the battlefield, led to a major strategic victory for the Union cause; one that compelled Lee to retreat away from Maryland and convinced President Lincoln to issue his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Though he did not live to see it, Irish’s service not only maintained “our Republicanism against the world,” but also helped make that system more inclusive. Such sacrifice was indeed monumental.

Danny Brennan is a PhD student at West Virginia University who works as a seasonal ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park. He is interested in exploring the culture and experience of Union soldiers in war and memory.

Endnotes:

[1] Joseph E. Crowell, The Young Volunteer: The Everyday Experiences of a Soldier Boy in the Civil War (Paterson, NJ: Joseph E. Crowell, 1906), 487.

[2] Thirteenth New Jersey Volunteers, Eighteenth Reunion, (Bloomfield, NJ: S. Morris Hulin, 1903), 4.

[3] Levi R. Trumbull, History of Industrial Paterson (Paterson, NJ: Carleton M. Herrick, 1882), 316.

[4] “How Hugh C. Irish Showed Faith in Nation,” The News (Paterson, New Jersey), July 12, 1951.

[5] Crowell, The Young Volunteer, 11.

[6] Samuel Toombs, Reminiscences of the War, Comprising a Detailed Account of the Experiences of the Thirteenth Regiment New Jersey Volunteers (Orange, NJ: Journal Offices, 1878), 3.

[7] Crowell, The Young Volunteer, 79.

[8] Crowell, The Young Volunteer, 133.

[9] D. Scott Hartwig, I Dread the Thought of the Place: The Battle of Antietam and the End of the Maryland Campaign (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023), 282.

[10] OR, ser. I, vol. 19, pt. 1, 502.

[11] Herber Wells letter, September 18, 1862, Passaic County Historical Society, https://lambertcastle.org/civil-war-letter-from-herber-wells/

[12] Sebastian Duncan to his mother, September 21, 1863, Sebastian Cabot Duncan Junior Papers, Box 2, Folder 13, New Jersey Historical Society.

[13] Herber Wells letter, September 18, 1862.

[14] Trumbull, History of Industrial Paterson, 339.

[15] Thirteenth New Jersey Volunteers, Eighteenth Reunion, 13.

[16] Susan Irish Loewen, “The Captain and Mrs. Irish,” The Castle Genie, Vol. 10, No 1. (2000), https://sites.rootsweb.com/~njpchsgc/mil/irish_capt_hugh.htm

[17] Thirteenth New Jersey Volunteers, Proceedings of the Second Reunion, (Newark, NJ: Amzi Pierson & Co, 1888), 42.

Great post, Danny!

Danny is the best Civil War historian of all time