Confederate Leadership at the Battle of Sharpsburg: Left Flank, 5:30 – 9:00 a.m.

The battle of Sharpsburg/Antietam occurred Wednesday, September 17, 1862. It lasted from sunrise to sundown. The Union first attacked on the Confederate left flank. While the fighting continued there, blue clad troops struck the center of the line. The battle slowly developed on the right flank and ended in a spectacular fashion.

Gen. Lee and his lieutenants communicated throughout the day with the assistance of their staff officers. Wing, division, and brigade commanders shuffled commands and rushed to the aid of their compatriots. Most met their assailants with extreme violence. It was a grotesque slug fest. In the end, Lee’s Misérables survived to fight another day, just nudging—and I mean nudging—out a win against the enemy.[1] It was at Sharpsburg that the Army of Northern Virginia’s leadership exhibited their finest tactical performance to date.

This series provides a glimpse at some deeds and actions of those commanders.

Preamble

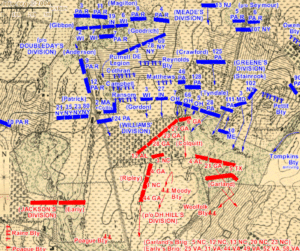

The rearguard action along South Mountain gaps bought Lee time and allowed him to regain the campaign initiative on Sept. 14, 1862. He ordered his scattered divisions to make a bee line to the quiet town of Sharpsburg, Maryland.[2] The Army of Northern Virginia started regrouping by the 15th. Lee reestablished his army into two wings: Maj. Gen. Longstreet oversaw the right and center. Maj. Gen. Thomas Jackson directed the left flank. Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry dutifully watched over the far left and directed artillery fire.[3] There were roughly 40,000 Confederates ready to fight; the Union counted about 87,000.

Tactical goals were straightforward on both sides The Union sought to destroy the Confederate army. Lee’s objectives included: 1) Survive to Fight another Day; 2) Kill as many Union soldiers as possible; 3) Hold off the enemy until reinforcements got to Sharpsburg; and 4) Defend the Ford near Sharpsburg.

The topography Lee chose had good and bad aspects. It was a strong defensive position in some respects. He set up his line on a series of hills just west of Antietam Creek.[4] It was a tight formation with the advantage of interior lines. There was about 1.5-2 miles between the left and right flanks. Lee could quickly get troops to the right place and the right time. The Potomac also lay to their rear and that would make for a quick get-away, but it wasn’t tactically ideal. One big push from the Union and the Confederates would be routed into the Potomac and finished off. It was risky, but the Virginian was a risk taker.

Lee recognized he needed all his talented officers. He made one of his biggest, and best, decisions right before the battle of South Mountain, Sept. 14. He reinstated Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood to his division command. As Lee put it, he couldn’t have “one of his best officers under arrest” before a big fight.[5] This move boosted morale and restored the hard-charging, capable division commander. Hood’s men fought well at South Mountain, but it was at Sharpsburg his soldiers played a pivotal role.

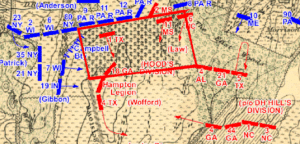

Left Flank – D. R. Miller’s Cornfield and West and East Woods

About sunrise, 5:30 a.m., Union battle lines appeared through the morning mist on Jackson’s left flank, trampling through D. R. Miller’s farm, West and East Woods and along Hagerstown Pike. Brig. Gens. William Edwin Starke’s and Alexander Lawton’s divisions met the assailants.[6] Starke went down, wounded three times and died within the hour. Lawton’s boys charged and pushed their opponent back through Miller’s soon-to-be infamous cornfield and West and East woods.

The Yankees regrouped and counterattacked; the Rebs found themselves surrounded on three sides, low on ammunition, and losing men and ground fast. Colonel Marcellus Douglass, commanding Lawton’s brigade, fell. His men dragged him back. An eyewitness described the scene.

“They carried him some distance and stood him down to mend their hold so they might carry him with more ease . . . while he was standing on one foot holding to them, he was struck in the left side of the abdomen, the ball passing through him . . . they all knew it must be fatal. Still, they took him up and carried him . . . but his suffering was so intense, and strength failing so, he desired them to lay him down, the balls, as well as shot and shell, still falling around them; and these are his words, the last he uttered on earth: ‘Lay me down, boys, and let me die; I had rather die on the battle-field than in the arms of my wife.’”[7]

Brig. Gen. Alexander Lawton was wounded as well. Brig. Gen. Jubal Early assumed command of Lawton’s division. The Union lines closed in on the Confederates in the cornfield from three sides.[8] One of Lawton’s staff officers found Hood: “General Lawton sends his compliments with the request that you come at once to his support.”[9]

File in! echoed through Hood’s division. The hungry soldiers dropped their breakfasts and went on the run.[10] His division smashed into the Union infantry and artillery. Hood later recalled.

“This most deadly combat raged till our last round of ammunition was expended. The First Texas Regiment had lost, in the corn field, fully two thirds of its number; and whole ranks of brave men . . . were mowed down in heaps to the right and left. Never before was I so continuously troubled with fear that my horse would further injure some wounded fellow soldier, lying helpless upon the ground.”[11]

The assault drove the blue lines from the cornfield and east woods, but it also shattered Hood’s command. Out of 2,304, his division lost 1,008 or 44% in 30 minutes or less.[12]

Three of D. H. Hill’s brigades covered Hood’s withdrawal. It was an uncoordinated and unfair fight. Col. Alfred Holt Colquitt’s brigade (made up of Georgia and Alabama boys) took the brunt of the enemy’s renewed offensive. It was the entire Union XII Corps. Colquitt’s command buckled back onto Brig. Gen. Roswell Sabine Ripley’s and Col. D. K. McRae’s men. The three brigades high-tailed out of Miller’s cornfield and out of the way of the twenty-plus regiments headed their way. It was about 9:00 a.m. The Confederate defense had collapsed. The initial casualties in Miller’s Cornfield and the surrounding woods were devastating. Confederates counted 4,000 killed or wounded. The Union had 4,200 casualties.[13] The left flank was there for the taking . . . or was it?

[1] I give the Army of Northern Virginia the win because they were still standing at the end of the fight. Lee’s number one tactical goal was to stay alive to fight another day. The American Battlefield Trust gives the Army of the Potomac the win. For further reading, Scott Hartwig provides an impressive, in-depth account of the battle at the command level, I Dread the Thought of the Place: The Battle of Antietam and the End of the Maryland Campaign. If you would like to read an excellent account of the battle from a soldier’s perspective, see John Michael Priest’s, Antietam: The Soldiers’ Battle. Maps in this blog can be found at https://antietam.aotw.org. This is a great online source.

[2] South Mountain was a Confederate tactical loss, but winning wasn’t Lee’s objective. It was about buying time. Walter Taylor, one of Lee’s staff officers, notes the majority of troops on hand were deployed by Sept. 15, see Walter Taylor, General Lee: 1861-1865, 128.

[3] For orders of battle, see https://antietam.aotw.org/oob.php. Taylor says Lee fielded 35,000 men, 134.

[4] Taylor, 129.

[5] Hood’s brigade captured some ambulances at 2nd Manassas. Maj. Gen. Nathan Evans wanted Hood to turn over the ambulances to him. Hood refused. He was arrested but allowed to stay with command. John Bell Hood, Advance and Retreat, 38-9.

[6] Starke commanded “Jackson’s division.” Brig Gen. J. R. Jones had command of Jackson’s division at the start of the battle, but Jones was wounded, stunned by an artillery round. Starke took command. https://antietam.aotw.org/officers.php?officer_id=75. Lawton replaced Richard Ewell after he was wounded at 2nd Manassas.

[7] For quote and a second account of Douglass’ death https://antietam.aotw.org/officers.php?officer_id=857.

[8] Jubal Early estimated Col. Douglass’ brigade sustained a loss of 554 killed and wounded out of 1,150, losing 5 regimental commanders out of 6; Hays’ brigade sustained a loss of 323 out of 550, including every regimental commander and all of his staff, and Col. Walker and 1 of his staff had been disabled, and the brigade he was commanding had sustained a loss of 228 out of less than 700 present, including 3 out of 4 regimental commanders. https://antietam.aotw.org/exhibit.php?exhibit_id=37.

[9] Hood, Advance and Retreat, 42-3. Lawton was taken to Henry Kyd Douglas’s house, see I Rode with Stonewall, 168. Hood’s division had two brigades and nine regiments.

[10] Hood, 43.

[11] Ibid., 44.

[12] Hartwig, Appendix: Strength and Casualties – Army of Northern Virginia.

[13] https://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/casualties.htm. Murfin says over 12,000 Union and Confederates were killed or wounded in the cornfield. See Murfin, 241.

I think the big question is, was the stand by Lee at Antietam worth it? Losses were high and the potential to be shoved into the Potomac was high. AP Hill’s arrival was just about a miracle in timing.

I think the phrase “Lee’s Misérables” deserves a special “wit” award — thanks!

Lee may of shown its finest tactical performance to date, but it was a horrible strategic mistake. To have 10,000 casualties out of 45,000 (American Battlefield Trust estimate), to put his army at risk of destruction (anyone but McClellan) solely to kill Union soldiers (who had plenty of them) and to fight to survive another day when he didn’t have to fight at all was military malfeasance. The destruction of Hood’s division was worth it? A.P. Hill’s last minute arrival part of the battle plan? Risk taking is a part of being a commander, stupid ones are not.

This is a great narration, keep it going.

I agree that the relatively short distance between the flanks, giving Lee good interior lines, had to be helpful given the topography, particularly on the southern(right) end. The maps are very helpful.