“I Beg to Be Sent Forward”: McClernand’s Agony and the Launch of the Vicksburg Campaign

ECW welcomes back guest author Devan Sommerville.

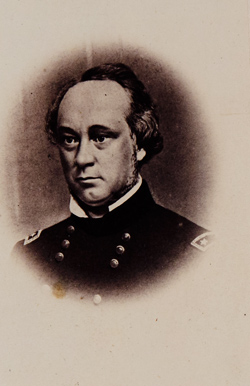

John McClernand’s alarm was growing. Deskbound at Springfield, Illinois, the general was proud of his success. In a matter of weeks, he and his staff had mobilized and dispatched dozens of newly organized regiments down the Mississippi River to the front.[1] Now he was forced to wait with growing frustration and awareness that command of the Vicksburg expedition was slipping away.

The seeds of his disappointment were planted in the orders issued by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck in late October. Proceeding to Springfield, McClernand was to complete the organization of regiments in Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa to be rapidly dispatched downriver for the purposes of organizing an expedition under his command “against Vicksburg and to clear the Mississippi River.” This was followed by a clause that would prove devastating to McClernand’s ambitions: “The forces so organized will remain subject to the designation of the general-in-chief and be employed according to such exigencies as the service in his judgment may require.”[2]

Halleck was a dedicated steward of army professionalism. McClernand, a politician-turned-soldier, held little regard for the West Point-trained officer corps.[3] The disdain was mutual. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles observed that McClernand “is no favorite, I perceive, with Halleck.”[4]

With the carefully worded orders in hand, Halleck turned his sophisticated understanding of the military bureaucracy – and his counterpart’s ambition – towards his own ends. The Federal army benefited from McClernand’s organizational energy, but leadership of the Vicksburg effort fell to a more capable subordinate: Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the Army of the Tennessee.

Grant, however, was initially unaware of McClernand’s new responsibilities. By early November, Brig. Gen. James Tuttle began reporting to Grant that regiments were arriving at Cairo, Illinois “with a kind of loose order to report to Gen. McClernand.”[5] Grant only received firm confirmation of McClernand’s activities when engineer James H. Wilson was assigned to him mid-month, having been pursued by McClernand for his expeditionary force staff.[6]

Grant shared Halleck’s misgivings about McClernand. There was friction between the two officers, including Grant formally describing McClernand’s official report after Shiloh as “faulty.”[7] He recounted that “he did not think the General selected had either the experience or the qualifications to fit him for so important a position,” and feared severe losses among the men under McClernand’s command.[8]

Nevertheless, Grant sought clarity from Halleck as to the extent of McClernand’s authority. Grant later explained that he had telegraphed Halleck on November 10 to seek direction, as “the mysterious rumours of McClernand’s command, left me in doubt as to what I should do.”[9]

Halleck was blunt. “You have command of all troops sent to your Dept,” he told Grant, “and have permission to fight the enemy when you please.”[10] Grant prepared his own campaign against Vicksburg, with “good reason to believe that in forestalling [McClernand] I was by no means giving offence to those whose authority to command was above both him and me.”[11]

McClernand’s suspicions were soon piqued. On November 13, he wired Stanton to express concern that Grant was asserting authority over the regiments for his planned expedition.[12] Stanton was quick to dismiss this, stating that they were “not to be withdrawn from your command,” but were only sent elsewhere, “temporarily for organization.”[13]

Halleck was more circumspect. “It is not important whether regiments go to Memphis or Helena,” he responded, noting that “detachments will be made from both places for the same object” – with no mention of McClernand’s leadership of the Vicksburg operation.[14]

McClernand’s correspondence grew increasingly frantic. He turned to political allies to press his case. Illinois Governor Richard Yates requested that McClernand “be soon sent forward in command of the expedition identified with his name.”[15] The following day, McClernand wired Stanton seeking to be ordered to proceed downriver to what he described as “my command,” to embark on an “early and successful movement” towards Vicksburg and re-opening navigation of the Mississippi River.[16]

Two weeks later, on December 12, McClernand contacted both Lincoln and Stanton with greater urgency. “I am anxiously awaiting your order,” he indicated, “sending me forward for duty in connection with the Mississippi expedition.”[17]

Stanton did not respond to McClernand for three days. His dispassionate reply did not calm the general: “I had supposed that you had received your orders from the General-in-Chief. I will see him and have the matter attended to without delay.”[18]

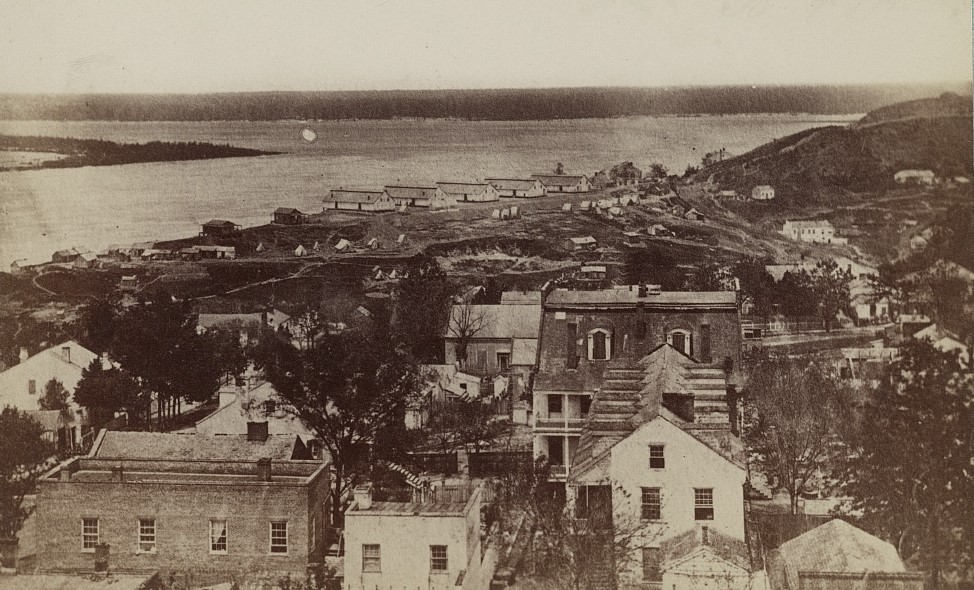

That same day, December 15, Halleck was completing preparations to commence Grant’s movement against Vicksburg before McClernand could arrive. His aide-de-camp, Col. Lewis Parsons, advised that the river transportation for the expedition was nearly ready and that “no efforts shall be spared to render the expedition a success and carry out your plans.”[19] The overall campaign was to be led by Grant; Sherman would command the riverborne expeditionary force. Embarkation was set for December 18.[20]

Having received no further update from Stanton, McClernand telegraphed Halleck directly with a blunt request, “I beg to be sent forward.”[21] The direct appeal to Halleck was the first open recognition that his fate – and his ambition to lead the advance on Vicksburg – was in Halleck’s hands.

A desperate McClernand wired both Lincoln and Halleck on December 17 with succinct requests: “I believe I am superseded. Please advise me.”[22] Stanton responded that afternoon, indicating surprise but that he would seek clarification from Halleck.

His response, reflecting Halleck’s input, was the death knell of McClernand’s grand ambitions. At its essence was the carefully prepared order issued in October. The troops mobilized by McClernand had been forwarded to Grant’s department for the expedition against Vicksburg. Rather than an independent command, McClernand would command a corps in the army, “assigned to the operations on the Mississippi under the general supervision of the general commanding the department.” Halleck had bested the politician at his own trade.

Halleck’s culpability in maneuvering against McClernand is not in doubt. Grant and Sherman, while expressing reservations about McClernand’s fitness, were at ease with exercising the latitude that Halleck granted them in accelerating their preparations.

The role of both Secretary of War Stanton and President Abraham Lincoln is more difficult to assess. Lincoln openly associated McClernand with the proposed expedition in both conversation and correspondence, and Stanton actively and repeatedly encouraged McClernand’s interpretation of his orders.[23] Nevertheless, the original order drafted by Stanton cannot be overlooked, nor the implications it would have on McClernand.[24]

An irate and chastened McClernand departed Springfield for the Mississippi theater on Christmas Day. Two days prior, he wed Minerva Dunlap, his second wife.[25] His mood was not improved by the telegraph received earlier on his wedding day from Stanton, claiming that it was not his “understanding that you should remain at Springfield a single hour beyond your own pleasure and judgment of the necessity of collecting and forwarding the troops.”[26]

McClernand’s press allies shortly announced the general’s departure, noting that “there has no doubt been a good deal of intriguing and maneuvering among the West Point interest to prevent the General’s assuming the command.”[27] McClernand, arriving shortly after Sherman’s bloody failure to seize Vicksburg at the battle of Chickasaw Bayou, heartily agreed. To Stanton, he bluntly stated, “I have been deprived of the command that had been committed to me.”[28]

Devan Sommerville is a consultant lobbyist based in his native Canada, living in Toronto, Ontario with his wife and young son. A lifelong student of the American Civil War and American Antebellum History, he holds an Honours Bachelor of Arts in History and a Master’s in Public Policy from the University of Toronto.

Endnotes:

[1] The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 401.

[2] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 282.

[3] Richard L. Kiper. Major General John Alexander McClernand: Politician in Uniform (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999), 135.

[4] Gideon Welles. Diary of Gideon Welles. (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), 1:127.

[5] John Y. Simon. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1977), 6:279.

[6] James H. Wilson. Under the old flag. (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1912), 120-121; 140-141.

[7] OR, Series 1, Vol. 10, Part 1, 114.

[8] Ulysses S. Grant. Personal Memoirs. (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885), 1:426.

[9] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 347.

[10] Simon, 6:288.

[11] Grant, 1:430-431.

[12] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 345.

[13] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 348-349.

[14] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 349.

[15] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 366.

[16] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 371-72.

[17] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 401.

[18] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 413.

[19] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 413.

[20] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 409.

[21] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 415.

[22] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 420.

[23] David Dixon Porter. Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War (New York: D. Appleton, 1885), 122.

[24] Kiper, 152.

[25] Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago: December 28, 1862), 2.

[26] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 462.

[27] Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago: December 27, 1862), 2.

[28] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 528.

With focus on Major General John McClernand, this report by Devan Sommerville on the “politically motivated attempt to place McClernand in command of troops bound for Vicksburg” is informative and accurate… as far as it goes. Every condensed version of history suffers from “errors of omission.”

A trend has arisen in recent years to incorporate “Confederate Memory” into the narrative of the Civil War. I personally see this as problematic, because “recollections, passed down through generations” have too great likelihood for embellishment. And when “remembered history” is conjoined with recorded history, the two formats usually do not mesh. Which format takes priority?

A little-known operation took place in Mississippi during November/ December 1862 that had potential implications for McClernand’s command of the campaign against Vicksburg. The following video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oCdrc6JNzqs features Jerry Skinner explaining “How General Grant’s wife, Julia, was nearly captured at Holly Springs” [while the maneuvering for McClernand’s official command of the attempt on Vicksburg was ongoing.]