Bushrod’s Logjam

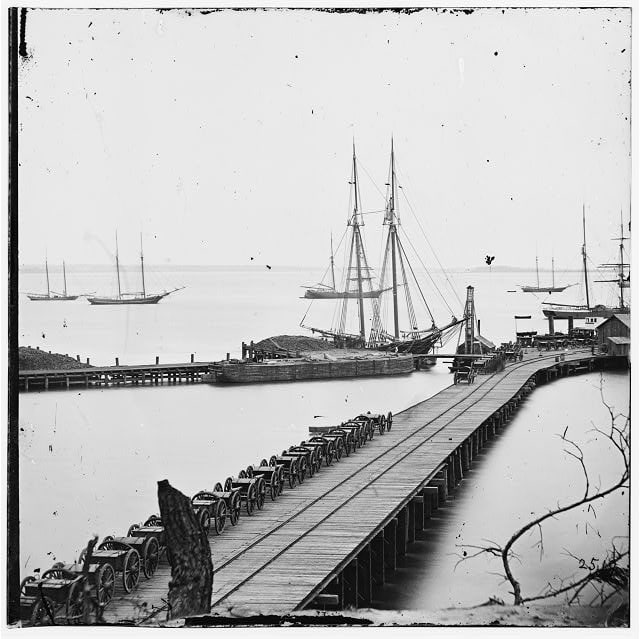

During the siege of Petersburg, supplies for the Army of the Potomac passed through City Point. A tiny fishing village before the war, it became a massive logistics center with eight acres of wharves, at times loading and unloading over 100 ships a day. Far from the main lines, the problem of interrupting this traffic vexed Confederate leadership. Major General Bushrod Johnson proposed an unusual plan that could render City Point wholly inoperable.

“I would suggest that if the present rain continues until a flood or good rise is produced in the James River, 1,000 men with axes could, in a few days, cut from the banks of that river and float together trees enough to sweep the Yankee fleet out into the Atlantic Ocean…The freshets in the James River are, I understand, powerful in volume of water and swiftness of current; the trees cut and floated together before a rise could be strongly united, forming almost a solid mass, and no power or Yankee ingenuity could withstand the crushing power of this raft, hurled down the stream by the accumulated torrents of the river.”[1]

There is no evidence of further consideration to this proposal, but could it have been effective? The hydrologic conditions seem promising. Freshets are sudden increases in the height and speed of a river often due to rainfall, and the James was prone to these changes. Historical data from 1870 to 1900 shows rises of over fifteen feet in Richmond, twenty miles upstream, were not uncommon. The two highest readings, 27 and 28.6 feet, were the earliest measured, in 1870 and 1877.[2]

Johnson’s use of the term “raft” is not suggestive of tying the logs together in the style of a crude floating vessel. Raft also referred to a natural logjam, the most significant of which clogged the Red River. Erosion along the banks swept countless trees into the waterway for centuries, accumulating to a length of 60-70 miles long. First recorded by Europeans in 1722, it severely impeded navigation.[3] During the Red River Campaign, Union commanders failed to adequately prepare for its challenges, while rebels utilized their knowledge of its features to forestall the Federal flotilla.[4]

Combining an obstacle such as this with a crushing wall of water would no doubt prove disastrous to ships downstream. Whether 1,000 men with axes would be sufficient to create a massive logjam in a short amount of time seems to be more a question for a lumberjack or mathematician. The width of the James around City Point is near a mile, so to this amateur historian it seems unlikely.[5] It is unlikely that the Army of Northern Virginia would have been able to expend the necessary manpower during the siege. Only a bomb clandestinely loaded onto a ship carrying powder harmed operations at City Point, and only temporarily.[6] As far-fetched as Johnson’s idea was, there was no harm in asking.

[1] B.R. Johnson’s daily report, 19 July 1864, OR 40(3):783-784.

[2] “Freshets in James River, VA,” Monthly Weather Review 28, no. 4 (1900): 156. https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/mwre/28/4/1520-0493_1900_28_156a_fijrv_2_0_co_2.xml.

[3] Jacques D. Bagur, A History of Navigation on Cypress Bayou and the Lakes (Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 2001), 60-77. https://books.google.com/books?id=JyDh2ZgTcNsC.

[4] Danny W. Harrelson, Nalini Torres, Amber Tillotson, and Mansour Zakikhani “Geological influence of the Great Red River Raft on the Red River Campaign of the American Civil War,” Geological Society, London, Special Publications 473 (2019): 267-273. https://www.lyellcollection.org/doi/abs/10.1144/sp473.5.

[5] “Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge,” BridgeHunter, accessed September 15, 2025. https://www.bridgehunter.com/bridge/33803.

[6] “Confederate Sabotage at City Point.” U.S. Army Ordnance Corps and School. https://goordnance.army.mil/history/Staff%20Ride/STAND%202%20CITY%20POINT%20JAMES%20RIVER%20SHORLINE/Explosion%20at%20City%20Point.pdf.

Interesting concept, Aaron. Did not hear of Johnson’s proposal before. I agree with your assessment that success was highly unlikely. Thanks for the article.

Appreciate it Brian, glad you liked it!

The problem with freshets: predicting when they will occur.

A series of freshets, due higher-than-average rainfall during 1862, worked to the advantage of Union forces. In early June, heavy rain caused the Rappahannock River to rise over twelve feet. The rain persisted for several weeks, resulting in a channel depth of 22 feet from Chesapeake Bay to just below Fredericksburg; and even ocean-going transports were among the dozens of vessels put to use transporting men, artillery, horses and supplies down the Rappahannock to White House on the Pamunkey.

The freshets were even more impressive on the Western rivers. A freshet on the Tennessee River late January/ early February 1862 caused the navigable river to rise over fifty feet; Confederate torpedoes broke their anchors and floated “harmlessly” downstream, allowing Flag-Officer Foote’s flotilla of gunboats to assault Fort Henry from point blank range. Fort Henry itself nearly flooded during the assault: at the moment of surrender, on 6 February, the rising river found its way inside, allowing a Union rowboat to proceed through the Sally Port and take the surrender of General Tilghman.

The nearby Cumberland River also suffered a freshet shortly after Fort Henry fell. Confederate barges loaded with stone had been sunk months earlier at Lineville, successfully blocking the channel. The rising water overtopped the barrier in early February, permitting Foote’s gunboats to proceed to within range of Fort Donelson.

All of this water had to go somewhere… flowing first into the Ohio River, this wall of water added to the flood on the Mississippi River. In late February the torrent reached New Orleans; an elaborate – and expensive – barrier raft stretched across the Mississippi River between Forts Jackson and St. Philip was swept away by the debris-laden flood. This raft was replaced by a less-robust string of floating hulks chained together, which was broken by Farragut’s forces in April 1862.

Very interesting Mike. It’s cool that the flow can be traced all the way to the ocean and had an effect on multiple offensives. I need to read up on naval stuff!

Great article. No idea that this proposal was considered by Johnson.