“The news from Kentucky is somewhat confused”: How Harper’s Weekly Reported on the Defense of Cincinnati

I’m endlessly fascinated with Civil War-era Harper’s Weekly archives. For millions of Northern civilians – not to mention the Southerners who got their hands on copies from across enemy lines – the illustrations in Harper’s had a critical impact on how they visualized the war. The Civil War was waged on a scale that had never before been seen in North America, and required both sides to mobilize their populations at a scale that was unprecedented in American history. Outside of the relatively few veterans of earlier, smaller wars, and the occasional militia drill, almost nobody had firsthand experience of what organized, armed conflict actually looked like.

In 2025, it can feel trite to say that a picture is worth a thousand words. Emerging Civil War ran an entire series exploring that idea, through the lens of Chris Heisey’s fantastic modern photography. But before the advent of widespread photography – let alone the nearly-infinite images at the fingertips of anyone with an Internet connection today – illustrated newspapers such as Harper’s and Leslie’s were immensely popular in large part due to their visual portrayals of the front lines. That often included depictions of events that seemed significant at the time, or that at least happened to occur near a Harper’s correspondent, but which today are virtually unknown to most students of the Civil War.

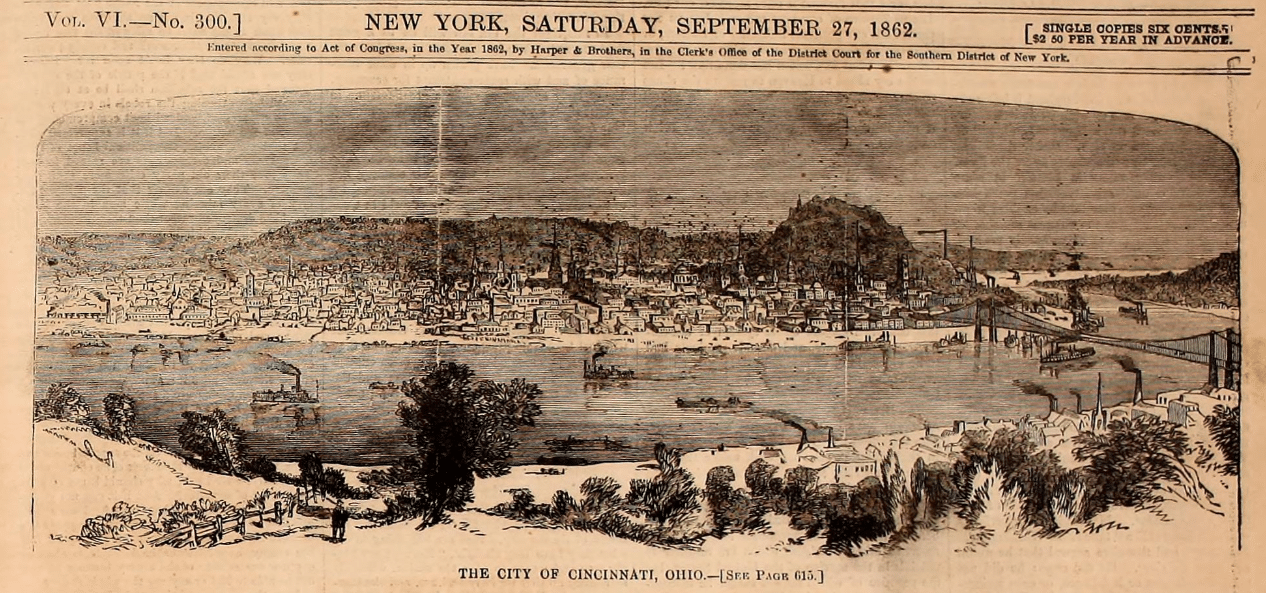

163 years ago today, Harper’s Weekly devoted a significant portion of their September 27, 1862 issue to what is now the little-known defense of Cincinnati, Ohio. In the late summer and early fall, Confederate armies under Generals Braxton Bragg and Kirby Smith slipped away from their Union counterparts, staged a rapid march north into Kentucky, and won lopsided victories at both Richmond and Munfordville.

Federal armies were caught flat-footed, with patchy intelligence at best about the whereabouts and strength of either Confederate force. That anxiety and uncertainty was shared by civilians who might be caught in the path of Bragg and Smith’s offensive. On September 27, Harper’s reported that, “Whether Bragg is still at Chattanooga, or elsewhere in Tennessee, we have no way of knowing.” – placing his force in entirely the wrong state, while acknowledging that “The news from Kentucky is somewhat confused.”[1]

Union leadership recognized that Bragg and Smith now had the inside track to the strategically vital cities of Louisville, KY and Cincinnati, OH. Smith dispatched between 6,000 and 8,000 troops under General Henry Heth to threaten Cincinnati – the same Heth who went on to find himself in badly over his head on July 1, 1863.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Cincinnati was a major city. By population, it was the 7th-largest in the United States, according to the 1860 census. Its strategic location on the north bank of the Ohio River, bordering Kentucky, made it a vital logistics hub for Federal armies marching south into the Confederacy in 1862.[2]

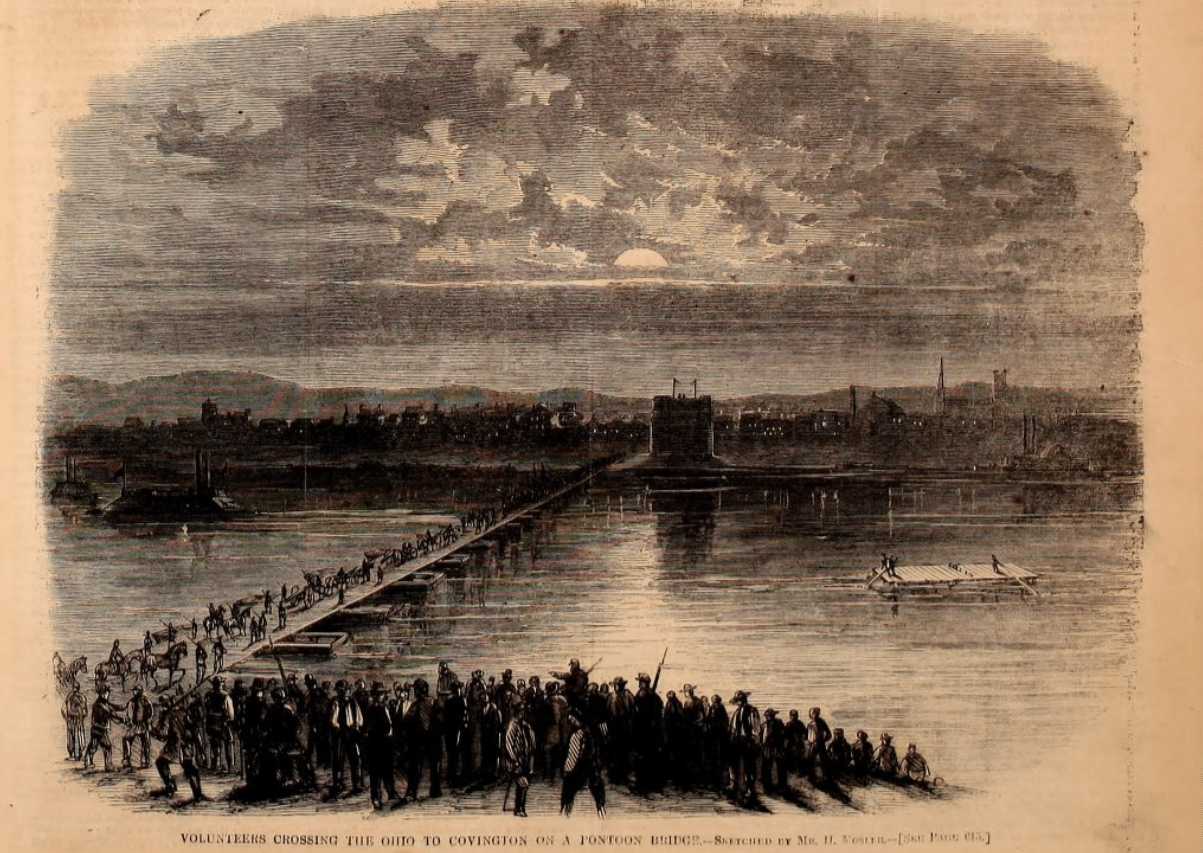

In response to the threat posed by Smith and Heth, Federal military and civilian leadership scrambled to mobilize a defense of the Queen City of the Ohio River. A mix of so-called “Squirrel Hunters”, local militia, and more organized Union units flooded into the city.

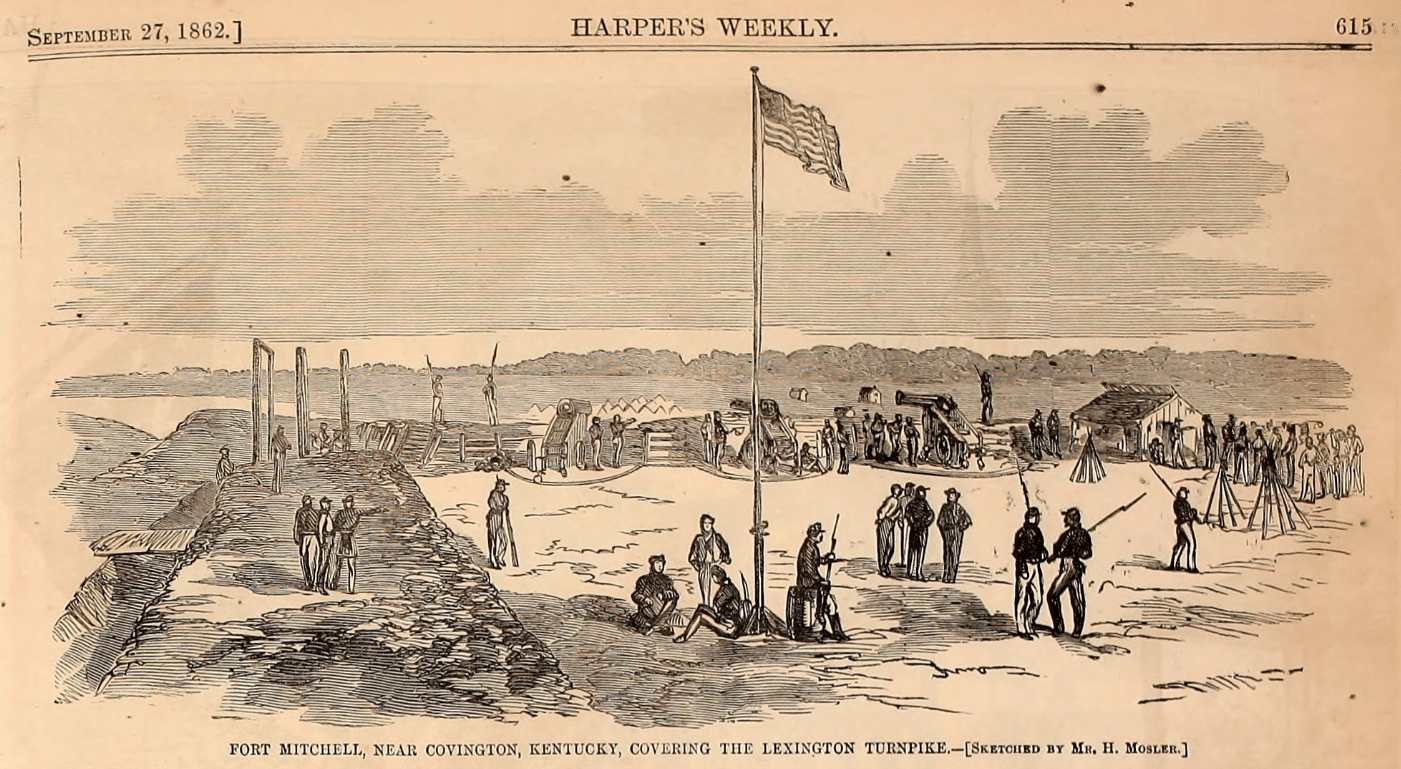

Under the command of generals Horatio Wright and Lew Wallace, they built a long string of fortifications south of the river, in and around Covington, KY. The Harper’s illustrations emphasize the entrenchments and earthworks, as well as the pontoon bridges that had to be hastily constructed to funnel men and supplies across the river.

In the moment, it was reasonable for observers on the ground to think that a major U.S. city was under imminent threat from Confederate forces that were on the march north. And without the fairly rapid response by Union leaders, it may have amounted to more.

But with the benefit of hindsight, the intense focus that Harper’s Weekly gave to the defense of Cincinnati was perhaps unwarranted. Outside of some skirmishing and reconnaissance, Heth’s Confederates declined to offer battle, and fell back by late September. After an inconclusive battle at Perryville, and stymied by their high command’s inability to coordinate different forces in the state, the Confederates eventually withdrew from Kentucky entirely.

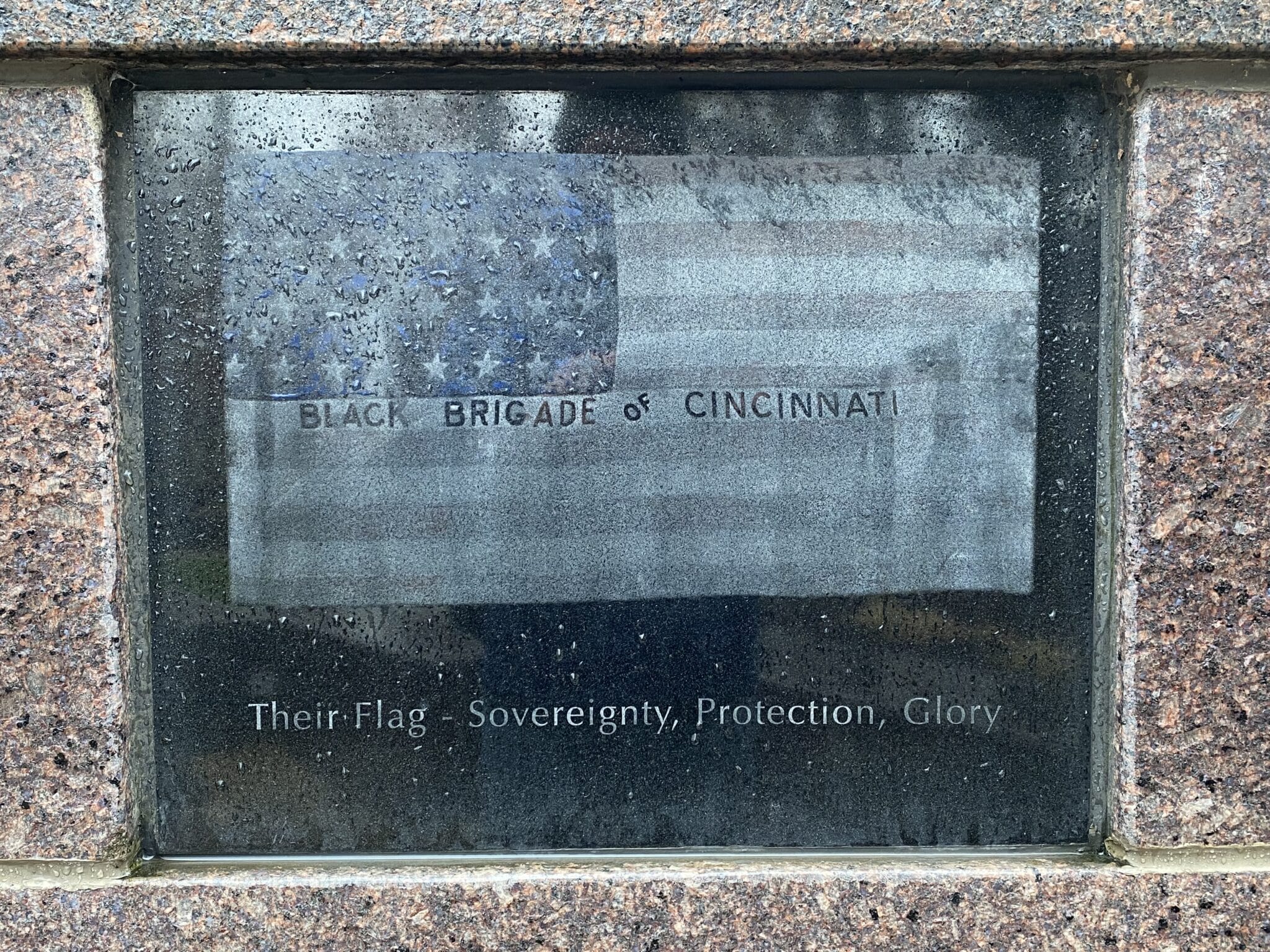

Today, this bit of Civil War history is remembered by a small portion of Cincinnati’s Riverfront Park along the waterfront that is dedicated to the Black Brigade of Cincinnati Monument. A series of interpretative signs offers a brief history of the campaign, while honoring the contributions of the members of the Black Brigade who were first impressed into service, and then subsequently volunteered to assist in the city’s defense.

[1] “Our Army At Cincinnati,” Harper’s Weekly, September 27, 1862. Accessed via Internet Archive.

[2] Statistics of the United States Census (Including Mortality, Property, &c.) in 1860, Washington Government Printing Office, 1866, XVII-XX.

Excellent article about one of the underrepresented aspects of Bragg’s Invasion. I do have one quibble, however. Heth was not in “over his head” on the first day at Gettysburg. He was surprised as any commander would be when there is a major failure of advance reconnaissance. He prudently adapted to the circumstances, held his position, and allowed Penders Division an opportunity to finish the days work, if in an incomplete manner. Davout was similarly surprised at Auerstadt, but in his case was opposed by a blundering Prussian opponent, which enabled him to continue the offensive without assistance. Heth’s opposition was of a far higher level than Davout’s.

Overall, a balanced and informative introduction to a “difficult time for the Union in the Western Theatre:” the period from July 1862 (when Halleck’s force came to a premature halt at Corinth Mississippi; Halleck was called east to Washington to become General-in-Chief of the Union Armies; and the Rebel counter-offensive began) until January 1863 (when John McClernand’s efforts to take major command in the west were neutralized and U.S. Grant resumed “unchallenged” command in the West.)

In 1862, Cincinnati Ohio was one of the richest cities in America. A raid conducted by John Hunt Morgan in July 1862 reached Cynthiana Kentucky, only 57 miles south of Cincinnati; and it was increasingly believed that Cincinnati, with most of its eligible fighting men elsewhere, presented a tempting target of opportunity, with potential to be easily captured and held for ransom. Was Cincinnati really threatened? The people of Cincinnati believed they were; Lew Wallace believed they were. We will never know, for certain. But the rapidly constructed and sound defences ensured that the city would not become “easy pickin’s.” And the defensive works proved a source of pride for Cincinnati’s Black community, which contributed necessary manpower to their construction.

As regards “reporting of the news,” local newspapers during the Civil War mostly did commendable work with written reports; some provided maps on the front page; almost none provided sketches or other news-related images. Three national “illustrated magazines” provided sketches, maps and written reports – for the Union audience: Harper’s Weekly; Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper; and the New York Illustrated News. And for the Rebels: Southern Illustrated News, published from September 1862 in Richmond. Many of these are available online…

Great Post, Pat. You are correct about the anxiety and uncertainty of the Rebel intent in Ohio and specifically Cincinnati during their march north. Interesting the pictures from Harper’s.

I’m wondering how they got that first sketch from Sept. 1862 showing a bridge that wasn’t there at the time. The Roebling Suspension Bridge was started before the war, but construction was suspended during the war and not finished until 1867. Only the towers were built, as can be seen in the second sketch. Also, it’s in the wrong location…it should be about the center of the drawing. And it is the prototype for Roebling’s larger and better-known Brooklyn Bridge.

Online resources say that Harper’s Weekly had a circulation around 100,000 in 1861 and grew to 200,000 during the war. Cost six cents an issue.

Thanks for an interesting and thoughtful narrative about the important city of Cincinnati, which is another of the many Civil War places that played a part in the great struggle to preserve the union.