Interservice Transfers: James K. Langhorne

When thinking of combatants in the U.S. Civil War, it becomes natural to divide members of the armed forces into categories, first by service branch, then by different subdivisions (infantry vs. cavalry, ships assigned to, regiments a part of). However, thousands of combatants ended up serving in multiple service branches, such as a soldier transferring to the navy or a sailor transferring to the army. One such case involved Virginian James K. Langhorne, who found himself transferring from the Confederacy’s provisional army to its navy, before supposedly ending up back in the ranks at war’s end.

Born in 1839 and raised in Portsmouth, Virginia, James grew up with two other siblings. By 1860, he was a young machinist.[1] He enlisted for 12 months as a private in Col. Raleigh Colston’s 16th Virginia Infantry Regiment on April 20, 1861, just days after Virginia declared its secession.[2] Langhorne was with the regiment as it remained in the Norfolk area through 1861, and in May 1862 his enlistment was extended for two more years.

The 16th Virginia joined the Army of Northern Virginia, as part of Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s brigade, in time to participate in the Seven Days campaign. Langhorne was present throughout and emerged unscathed, though the regiment suffered 91 casualties of the approximately 500 men present at the battle of Malvern Hill.

From there, Mahone’s brigade marched north, participating in the battle of Second Bull Run. It proved another costly engagement, with the regiment losing 154 men, including Col. Charles A. Crump, who was killed. Private Langhorne was “slightly wounded” that August 28 and spent the next several months in the hospital recuperating.[3]

While in the hospital, he applied to be appointed an engineer in the Confederate Navy. With his antebellum experience as a machinist, Langhorne’s skills were certainly in demand. He received an official appointment as a third assistant engineer on January 19, 1863, receiving an official discharge from his regiment that same day. It was a significant rise in position, for third assistant engineers were warrant officers who ranked “with midshipmen,” meaning they held an equivalent grade as an army second lieutenant.[4]

Now under naval jurisdiction, Langhorne was ordered to Charleston, where he joined the crew of the ironclad Chicora. Whether he made it to the ironclad in time to participate in its January 31, 1863, sortie out of Charleston, where Chicora attacked USS Keystone State and forced the blockader to strike its colors, is not known.[5] Regardless, by the time Langhorne was on the ironclad, the battle was the only thing the remainder of the crew could talk about.

Langhorne remained on Chicora through 1863 and into 1864, guarding Charleston harbor and striving to help keep the ship’s engines operating through the active summer 1863 operations in the city.[6] Each evening, either Chicora or its sister ship Palmetto State alternated as the designated guard ship near Fort Sumter, ready to strike Federal ships should they launch a surprise night assault.[7] Chicora also helped transport soldiers to Morris Island, allowing rotation of soldiers in Battery Wagner as Maj. Gen. Quincy Gillmore’s siege of the position developed.

In early September the ironclad covered sailors as they manned boats to effect a near-flawless withdrawal of Battery Wagner’s personnel.[8] On September 9, 1863, Chicora “had a good chance to work her guns” against Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren’s landing force in their failed amphibious assault against Fort Sumter.[9]

In 1864, Chicora continued patrols and acting as a guard ship, even as operations against Charleston waned. That year, Langhorne received an appointment as a third assistant engineer in the Confederacy’s provisional navy, which was created as an avenue to allow for faster temporary promotions of officers for the war’s duration for merit and combat performance, supplanting the traditional naval promotion system through seniority of rank in each grade.[10]

Around November 1864, Langhorne was transferred from Charleston north to Richmond. Once there, Captain John K. Mitchell, flag officer of the Confederacy’s James River Squadron, assigned Langhorne as one of the five engineers on CSS Virginia II, the squadron’s flagship.[11] He was present aboard the ironclad during the failed January 1865 Rebel naval advance towards City Point that became the battle of Trent’s Reach.

When Richmond was evacuated in April, Rear Admiral Raphael Semmes ordered the James River Squadron scuttled. Confederate sailors on the squadron’s ships boarded trains and ended up acting as an improvised artillery brigade that surrendered with Joseph Johnston in North Carolina. Other sailors manning fortifications and entrenchments around Richmond ended up joining Robert E. Lee’s withdrawal, surrendering to Federals at the battle of Sailor’s Creek.

Engineer Langhorne did not join either group however. With his ironclad scuttled and the Army of Northern Virginia on the march, Langhorne supposedly found his old regiment, the 16th Virginia, and rejoined its ranks. Langhorne’s obituary from 1910 claims he did so “to the end of the war,” – as does Confederate Veteran magazine – though his name is not among the 124 officers and men of the 16th Virginia who surrendered at Appomattox Court House, or among any of the names compiled from Appomattox surrenders.[12]

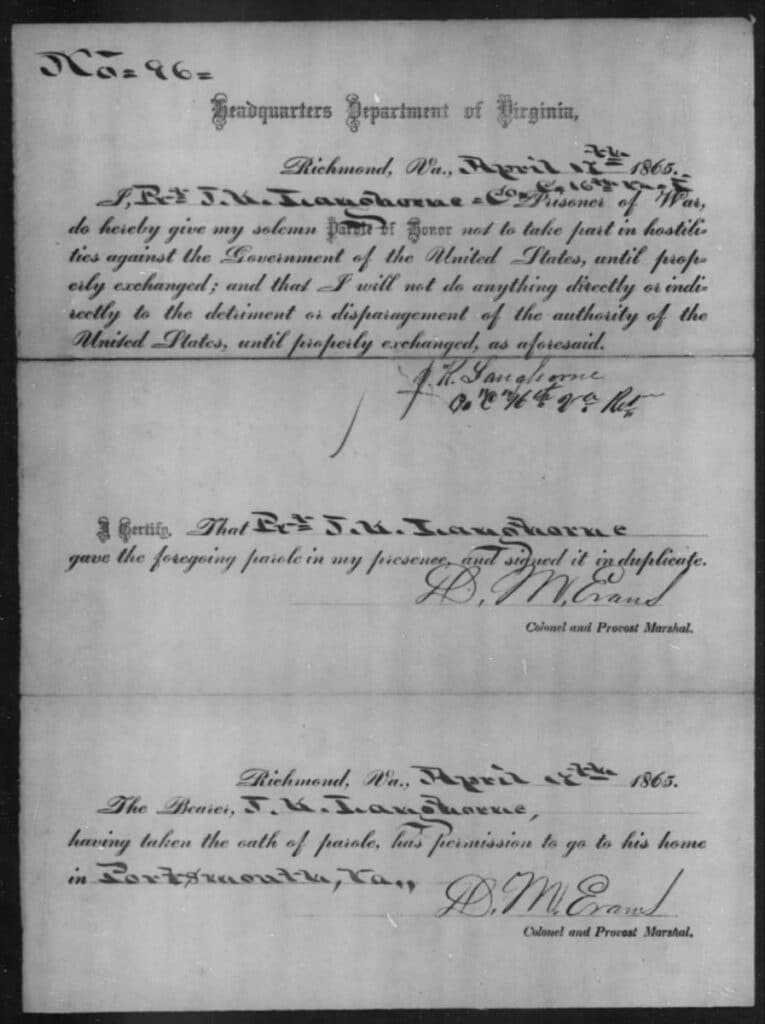

Despite that, there is some evidence that Langhorne indeed rejoined the ranks of his old 16th. His army service record does contain a parole, dated April 17, 1865. The parole document lists Langhorne as a private in the 16th Virginia. It was issued in Richmond.[13] So, if Langhorne indeed rejoined his regiment, he must have straggled from it during the march, for he ended up returning to Richmond after the Appomattox surrender to get his own parole issued. Either that, or he never rejoined his old regiment, became a naval engineer trapped in Richmond as the city evacuated, and when he surrendered to Federal troops he felt it better to claim being a soldier instead of a sailor.

After the war, Langhorne returned to Portsmouth, Virginia. He married Fannie Hill in 1873. Together they had five children, two boys (Eugine and John) who each died before their second birthdays, one girl who also died young (Mary), and two girls (Frances and Julia) who lived well into the second half of the 20th century.

With ties in location and wartime experience to the navy, James Langhorne found work postwar as a machinist working at the Norfolk Navy Yard. He also became the first commander of the Stonewall Camp, United Confederate Veterans chapter in Portsmouth and Norfolk.[14] Langhorne died in 1910, one of the few Civil War participants who joined the army, then transferred to the navy, before supposedly picking up a musket and rejoining the army’s ranks once again.

Endnotes:

[1] Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, Portsmouth, Virginia, for James K. Langhorne, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[2] Service Record of James K. Langhorne, 16th Virginia, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia, M324, Records Group 109, U.S. National Archives.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Regulations for the Navy of the Confederate States. 1862 (Richmond, VA: MacFarlane & Fergusson, 1862), 9.

[5] R. Thomas Campbell, ed., Engineer in Gray: Memoirs of Chief Engineer James H. Tomb, CSN (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2005), 58-59.

[6] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 2, Vol. 1, 283.

[7] John M. Stickney, Promotion or the bottom of the River: The Blue and Gray Naval Careers of Alexander F. Warley, South Carolina (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), 140.

[8] J. Thomas Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy (New York: Roger and Sherwood, 1887), 698-699.

[9] Campbell, Engineer in Gray, 63.

[10] Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the Navy of the Confederate States to January 1, 1864 (Richmond, VA: MacFarlane & Fergusson, 1864), 50.

[11] ORN, Series 2, Vol. 1, 311.

[12] “James King Langhorne,” Virginian-Pilot, Norfolk, VA, April 13, 1910; “James K. Langhorne,” Confederate Veteran, Vol. 19, No. 9, September 1911, 437; The Appomattox Roster: A list of the paroles of the Army of Northern Virginia issued at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865 (New York: Antiquarian Press, 1962 edition), 347-348, 352-354.

[13] James Langhorne parole, Service Record of James K. Langhorne.

[14] “James King Langhorne Dead,” The Ledger-Dispatch, Norfolk, VA, April 12, 1910.

I enjoyed this intriguing tale! What inspired you?

I just stumbled on the parole document while searching for other things, set it aside, and looked up more when I found the time. Just one of those records you run into while looking through the archives.

Wasn’t the first skipper of the Hunley — the one they lost with almost all hands — an officer from CSS Chicora … and then his relief was an Army Lieutenant who “transferred” to the CSN?.