Echoes of Reconstruction: Best Books of 2025

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back Patrick Young, author of The Reconstruction Era blog.

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back Patrick Young, author of The Reconstruction Era blog.

Every year I have observed October as National Book Month by telling you which volumes published over the previous twelve months are the best books on Reconstruction that I have read. I usually look forward to posting the list, but this year I have a strange foreboding as I write this. Newspaper literary supplements have been axed, or maybe the entire newspaper has gone out of business. For those following Civil War histories, several of the magazines dealing with the subject, like the Civil War Times, have ceased publishing altogether.

In August, we found out that the Associated Press (AP), America’s largest news agency, has stopped publishing all book reviews. Ron Charles, the book review writer for the Washington Post, devoted a column to this extinction of the book review. Charles writes: “The death of book reviews is not greatly exaggerated, but it is greatly protracted. This time, the bell tolls for book reviews from the Associated Press.” I still read books, so I will keep reviewing, as will the other book reviewers at Emerging Civil War. If you like book reviews, keep reading and sharing them.

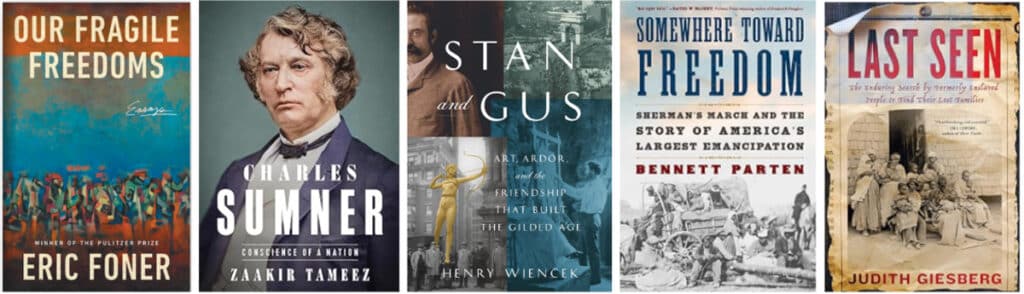

Here are this year’s best. These five new books cover the interplay between the military conquests of the Civil War and the start of Reconstruction, the search by freed slaves for their families, a collection of essays by one of the greatest historians of Reconstruction, and a biography of an outstanding legislator fighting for human rights for African Americans. I supply a link for each title where you can find my full review.

Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families by Judith Giesberg published by Simon & Schuster 336 pages (2025) is the culmination of a long project by Professor Judith Giesberg and her students at Villanova University. They searched for “Want Ads” published from the days of slavery and the Civil War onward placed by African Americans looking for their family members from whom they had been forcibly separated by slave sales. From these short advertisements Giesberg’s new book tells you where the person placing the ad lived, when and where their families had been broken up by a white society that often ignored family attachments among People of Color, and whether the families were reunited. While there are some searches with happy results, others end in heartbreak.

Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation by Zaakir Tameez published by Henry Holt 640 pages (2025) was a surprising book for me. I had read Harvard Professor David Donald’s Pulitzer Prize-winning two-volume biography of the Massachusetts senator, and I felt that I knew Sumner’s life, but I was struck by Tameez’s new interpretation.

Zaakir Tameez started writing this book while he was in Yale Law School. I can’t understand how he could pursue this academic target while working 60 to 70 hours a week to get through law school! I learned a lot from this biography that showed an interplay between the life that Sumner lived and his outstanding advocacy for human rights (and yes, Sumner used the term “human rights” more than three hundred times in his writings). Sumner grew up around Black people and made his home as an adult in Boston’s only Black neighborhood.

He joined in a lawsuit to end segregation with one of the few admitted Black lawyers in the United States, and he helped another Black attorney become the first Person of Color admitted to the Supreme Court Bar. In addition to his work to free the slaves and provide Constitutional protections for Blacks at the end of the Civil War, Sumner also formed alliances with many Blacks at a personal and professional level.

Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman’s March and the Story of America’s Largest Emancipation by Bennett Parten published by Simon & Schuster 272 pages (2025) is an outstanding work combining a history of the 1864 March to the Sea and the freeing of tens of thousands of slaves in Georgia. The March presented enslaved people with the sudden end of slavery if they followed the soldiers. The incorporation of tens of thousands of Black refugees into the train following Sherman presented to the Federal government an opportunity to begin establishing clear lines of protection to African Americans. Sherman’s men sometimes sheltered the escapees, and sometimes abused them, but the overall effect was to hasten the end of slavery a year later.

Sherman did see the liberationary impact of his armies marching through Georgia. Parten says that:

“Despite his tough talk about the folly of emancipation and its impact on the army, Sherman’s record while commanding…is mixed. On the one hand, he abided by the terms of the Second Confiscation Act, which went into effect as he began his governorship. When enslaved people came into the city seeking refuge, he refused to send them away or return them to their masters, as the law prescribed, despite countless numbers of local slave owners writing him for help. To his credit, he remained resolute on that score and relished writing back to planters, rebuking them for having the nerve to ask such a thing in a time of war.”

Stan and Gus: Art, Ardor, and the Friendship That Built the Gilded Age by Henry Wiencek Farrar, Straus and Giroux pages 320 (2025) is an intriguing portrait of two artists who helped construct the post-war monuments that helped shape how Americans saw the war. Stanford White, America’s most well-known architect, and Agustus St. Gaudens, an Irish-born sculptor, were responsible for New York’s mounted golden statue of William T. Sherman outside the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan, Admiral David Farragut’s statue on display in Madison Square Park in Midtown, the Robert Gould Shaw 54th Massachusetts monument on Boston Common, and dozens of other well known memorials. The book examines the historical sculptures they created, the friendship of the two men, and the likely predation of Stanford White on girls and his death in Madison Square Garden. Together, the men made some of the most outstanding works of historical statuary that told the history of that war to the general public and that heroicized the warriors and battles of the War of the Rebellion.

While the artistry of the two men is widely recognized, Stanford White’s end was even more famous than his architecture. White was murdered in front of a large audience by the husband of Evelin Nesbit, the original “Gibson Girl.” According to Nesbit, she had been raped at only sixteen years of age by a man nearly three decades older than she. While White’s friends disbelieved her story because the two maintained a relationship for several years after the alleged rape, as a poverty-stricken teenager she had little recourse for protection.

The final book is Our Fragile Freedoms: Essays by Eric Foner published by Norton, 466 pp. (2025). Eric Foner is the most recognized modern historian of Reconstruction. Over the years, Foner has won the Bancroft Prize, the Lincoln Prize, and the Pulitzer. His most famous book is Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 put out in 1988. It set the standard for histories of Reconstruction.

The new volume is a collection of essays by Foner from popular sources on Reconstruction, the Civil War, slavery, and the politics of memory after those great events of the second half of the 19th century. The sixty essays in the 466-page book cover the lead up to the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln’s views on slavery both before the war and his changing position during the conflict, and the effort of Black abolitionists to transform a struggle over “states rights” to one in which human rights took precedence. Normally I don’t review collections of essays from academics since they often leave the lay reader behind, but Foner’s new book is an accessible introduction to the latest thinking on the overthrown revolution in America’s attempt to bring racial equality.

Thank you for this! I agree with the continued importance of book reviews. (I write and read them.) This is a good list of books.

Thanks very much.

I’m currently reading The Great Dissenter, a marvelously written biography about John Marshall Harlan. Last week, while I was at my 50th reunion at Centre College, we dedicated a statue to him as one of our famous alumni. Great posting!

Thanks, I do talk about Harlan for a little while in my course at Hofstra Law School, as well as Frank Murphy for offering a different path in U.S. law. I must read that book!

I have read quite a few Civil War era books but I have a limited knowledge about the Reconstruction era, except for the standard narrative that the failure of Reconstruction led to Jim Crow and 100 years of segregation.

I’m wondering, however, could Reconstruction have been structured and implemented better than it was, possibly resulting in a better relationship – sooner – between whites and blacks? Would Lincoln have found a way to achieve that goal? Did the Radical Republicans, in their desire to “teach the Confederates a lesson”, help create an environment, which precipitated the violence and discrimination that followed?

As a Northerner, I don’t have the family history that connects me to the South and as a result I don’t feel the need to defend the actions of those, which led to the segregated South of the last half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th. But I wonder if both sides were responsible – maybe not equally – for the lost opportunity to create an environment conducive to racial harmony, over time, which would have avoided what occurred for 100 years.

As I said, I haven’t read much about Reconstruction. I am interested in doing so, if the publications are objective and balanced. I’m less interested in reading anything that lays the full blame, at one side or the other.

I just got a copy of Tameez’s biography of Sumner. How does it compare to Donald’s two volumes?

I liked the new volume better.

Typically when there is an established biography of a figure and a new bio comes out many years later, after reading them both I often wonder why the new book came out. With Tamees’s book I did not have to wonder at all. Very good bio.

I just completed my first biography of Grant, Soldier of Destiny, which forced me to reevaluate my thoughts on Grant. The books mentioned above will give me a window into the reconstruction period, which is one of the most understudied periods in American history, as I believe it’s the foundation of the problems with race relations we see today.

I’m really interested in Tameez’s book on Sumner, who, as I learn more about him, is becoming a “politician of interest” for me in the antebellum and Reconstruction eras. Is there a review of that book yet?

Here is my review of the Sumner book:

https://thereconstructionera.com/charles-sumner-conscience-of-a-nation-by-zaakir-tameez/