“A life already protracted much beyond the usual span of man”: Winfield Scott’s Retirement

164 years ago today, Brevet Lieutenant General Winfield Scott withdrew from active service and relinquished his role as the commanding general of the United States Army. Formally accepted a day later, this ended his career as the longest-serving general in American history.

Born near Petersburg, Virginia in 1786, Scott fought in the War of 1812. He’s perhaps best-known for his Mexican War exploits, leading an American army at the siege of Vera Cruz, before going on to capture Mexico City. He remained a significant figure in U.S. public life through the 1850s, and rose to become the commanding general of the United States Army.

Despite his record, more than a decade of desk duty made “Old Fuss and Feathers” something of an easy punching bag by the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. His preferred strategies were viewed as too cautious and slow, and his inability to serve actively in the field didn’t match the public’s expectations of a 19th-century military commander.

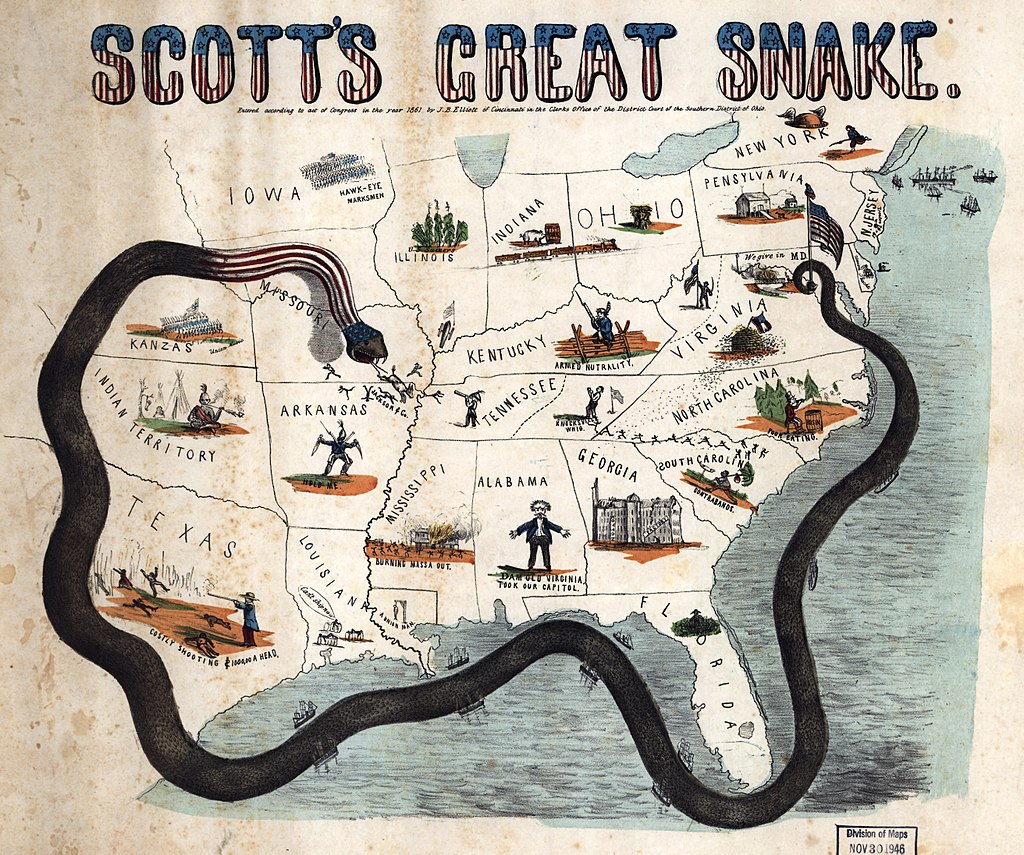

History has been somewhat kinder to Scott. His “Anaconda Plan” was widely derided at the time, but proved to be fairly forward-looking. The eventual Union grand strategy shared many of the same elements. Perhaps most critically, he recognized the importance of securing the nation’s capital, badly exposed as it was, during the earliest days of the rebellion.

In his retirement letter to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, the 75-year-old Scott cited a wide range of ailments that precluded continued active duty: an inability to mount a horse or walk any meaningful distance, dropsy, vertigo, and more. This was at a time when generals were expected to live in the field, and at times lead from the front. Many of the war’s successful, high-ranking generals were in their 30s and 40s: When the Confederacy fired on Fort Sumter, Grant was 38, Sherman was 41, Stonewall Jackson was 37, and Meade was 45.

In his retirement letter to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, the 75-year-old Scott cited a wide range of ailments that precluded continued active duty: an inability to mount a horse or walk any meaningful distance, dropsy, vertigo, and more. This was at a time when generals were expected to live in the field, and at times lead from the front. Many of the war’s successful, high-ranking generals were in their 30s and 40s: When the Confederacy fired on Fort Sumter, Grant was 38, Sherman was 41, Stonewall Jackson was 37, and Meade was 45.

Even Robert E. Lee, whose relatively advanced age and health conditions are often highlighted as impacting his ability to command the Army of Northern Virginia – possibly at Gettysburg, and certainly along the North Anna River in 1864 – was a full 20 years younger than Scott.

After his retirement, Winfield Scott was replaced by George B. McClellan – a much younger replacement, but no more active in the field for his youth. He retired to West Point, and was buried there after his death in 1866. Here’s the full text of his retirement letter:

Head Quarters of the Army

Washington Oct 31, 1861Hon. S. Cameron,

Secretary of War:Sir:

For more than three years I have been unable, from a hurt, to mount a horse, or to walk more than a few paces at a time, and that with much pain. Other and new infirmities — dropsy and vertigo — admonish me that the repose of mind and body, with the appliances of surgery and medicine, are necessary to add a little more to a life already protracted much beyond the usual span of man.

It is under such circumstances, made doubly painful by the unnatural and unjust rebellion now raging in the Southern States of our so lately prosperous and happy Union, that I am compelled to request that my name be placed on the list of army officers retired from active service.

As this request is founded on an absolute right, granted by a recent act of Congress, I am entirely at liberty to say it is with deep regret that I withdraw myself in these momentous times from the orders of a President who has treated me with much distinguished kindness and courtesy; whom I know, upon much personal intercourse, to be patriotic, without sectional partialities or prejudices; to be highly conscientious in the performance of every duty, and of unrivaled activity and perseverance.

And to you, Mr. Secretary, whom I now officially address for the last time, beg to to acknowledge my many obligations for the uniform high considerations I have received at your hands, and

Have the honor to remain,

Sir,

With high respect,Your obedient servant,

Winfield Scott

His age and multiple illnesses explain his uncertain mood swings during the Sumter crisis. That being acknowledged, it is beyond comprehension why a man so consumed by vanity allowed himself to bloat into a human approximation of Jaba the Hutt.

There’s a humorous anecdote of Scott in retirement. He was voted a pension for life by Congress that could never be reduced, but complained in 1862 that the new income tax to which he was subject was “reducing” his salary. Revenue Commissioner George Boutwell said no, the income tax was a “tax,” not a reduction in salary. Frederick Douglass got wind of the story and wrote in his newspaper that it “was very small business” for a former commanding general to complain about new taxes that had been instituted in 1862 to help pay for the Union war effort, and Douglass “agreed with Boutwell that exempting Scott would set a poor example for other US military officers.” !

Great post, Pat. It is interesting that in Scott’s letter that he thanks the President for his kindnesses and praises him. Directly opposite of what his successor will do.

Thanks for remembering General Scott … it must have been a tough decision for the old general to resign on the eve of this looming conflict … but instead hanging around and kibitzing from the sidelines, Scott stepped down gracefully to make way for the next generation … good for him.