A Black Sailor’s Oral History Found!: Alex Huggins Wilson’s Experiences Convoying Treasure Steamers

Every time an author writes a book, there are a few inevitabilities. After opening your first copy of a new book, you could turn to almost any page at random and find a misspelled word or some other error. It is also inevitable that after publishing a book, authors always find another resource that they would have loved to have included in their work. This is just such a find tied to my 2024 book Treasure and Empire in the Civil War: The Panamá Route, the West and the Campaigns to Control America’s Mineral Wealth.

I have spent the last month or so diving into the WPA Slave Narrative archives housed at the Library of Congress. These are thousands of oral histories collected by employees of the Works Progress Administration as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Most of the people interviewed were aged 80-110, and almost all were born enslaved before or during the Civil War. The collection has its flaws. There are always inconsistencies when interviewing someone decades after an event, and many formerly enslaved people had good reason to tell stories that interviewers wanted to hear instead of a complete and full truth. However, these narratives also offer a rare lens into what life as an enslaved person was like, straight from the voices of those very people.

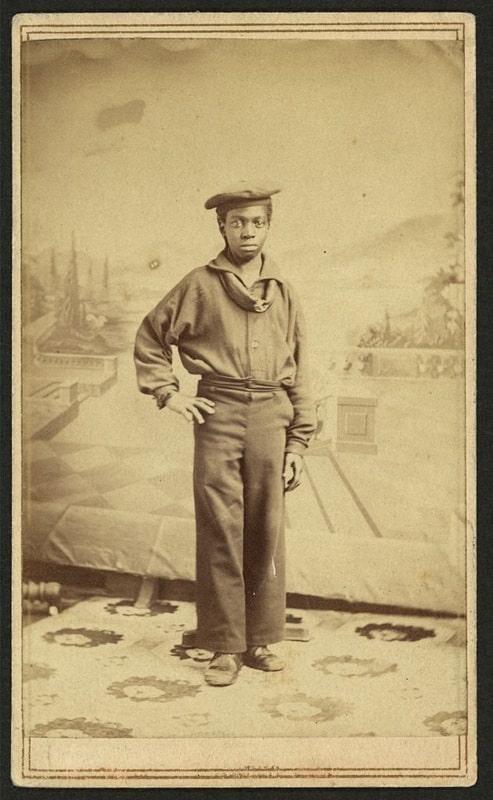

One of the men interviewed in Wilmington, North Carolina, was Alex Huggins Wilson, and his story was heavily linked to the Panamá steamer convoys protecting wartime shipments of gold from California to New York. Born in 1850, Alex was originally enslaved by L.B. Huggins. Alex escaped in 1863, noting in his interview, “Twa’nt anythin’ wrong about home that made me run away. I’d heard so much talk ’bout freedom I reckon I just wanted to try it, an’ I thought I had to get away from home to have it.”[1]

Alex ended up on a rowboat with a couple of other men seeking liberation. They were picked up off the coast by the Atlantic and Pacific Mail Steamer North Star, which spent that year traversing the shipping lanes between New York and the isthmus then part of the United States of Colombia. For example, in one trip, North Star departed New York City on April 1, 1863, was escorted through the Windward Passage between Cuba and Haiti by USS Santiago de Cuba, reached Colón, Colombia, on April 13, departed on April 17 loaded with $256,504 in gold, was escorted by USS Connecticut back up the coast, and returned to New York City unscathed on April 25, 1863.[2] It was just one of 29 similar journeys North Star made carrying bullion during the war.

Alex ended up signing on as part of the treasure steamer’s crew. He knew North Star’s mission well, conveying in his interview the steamer was “of the Aspinwal[l] Line, a mail an’ freighter runnin’ between Aspinwal[l] near the Isthmus of Panama and New York.”[3] That proved not enough to stave off boredom, and in 1864, at just 13-14 years old, Alex enlisted in the United States Navy.

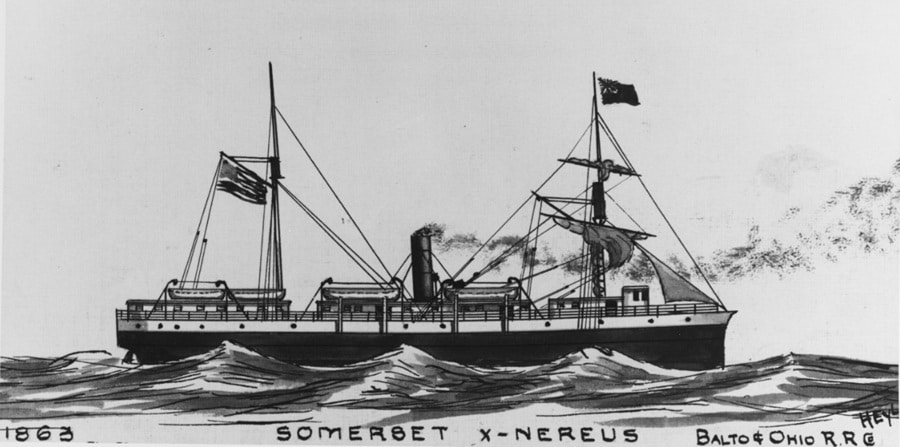

He was assigned to USS Nereus, a small converted screw steamer mounting 11 naval guns. While aboard, Alex claimed he was assigned as a steward to Nereus’s captain. He described the ship’s captain, John Cummings Howell, and the duties performed as his steward: “When the Captain wanted somethin’ good to eat he used to send me ashore for provisions. He liked me.”[4]

There is some corroborating evidence to support this enlistment. A man named Alexander Bender is listed in Nereus’s muster book. The record lists this Alexander rated as a third class boy who joined the navy on June 4, 1864 off the coast of Wilmington, North Carolina. The muster listed Alexander as a 4’7” 13-year-old whose job before enlistment was “servant negro.”[5] It is likely that this Alexander Bender is the same Alex Huggins Wilson recorded in the interview decades later.

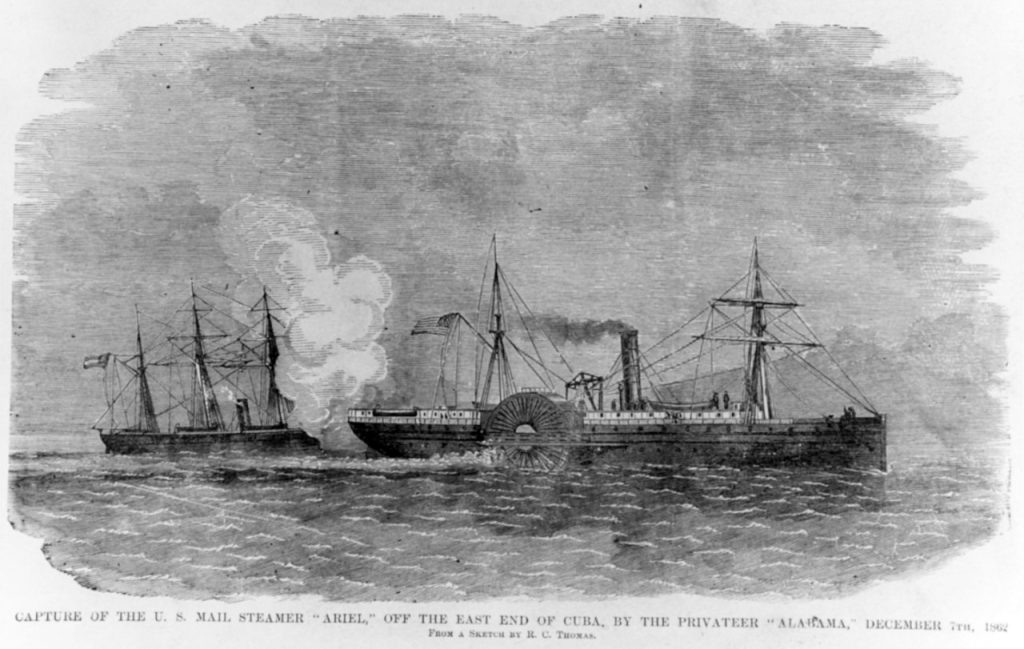

After spending time blockading Wilmington, Nereus spent part of 1864 convoying the very treasure steamer Alex previously worked on. Again, his interview provided insight onto both the overall mission and the specifics. Alex noted the reason for such convoys was “to keep the Alabama, a Confederate privateer, away.”[6] He was correct that the Confederate commerce raider Alabama prowled the Caribbean during the war in search of treasure steamers. The Confederate ship even captured one in December 1862, while the raider Florida captured another ship transporting silver in 1863.

In September 1864, Nereus was assigned to convoy the treasure steamer North Star for its journey from New York to Colón and back. The ships departed New York on September 3, 1864. While approaching Mayaguana Island, they encountered USS Powhatan. Sailors on Powhatan saw the treasure steamer, with “another steamer” close by, and assumed Nereus was a chasing Confederate.[7] Alex and the other Nereus sailors ironically thought Powhatan was also a Confederate ship: “The Mast Head [lookout] reported a strange sail,” Wilson recalled. “’Where away?’ ‘Just ahead’. She seems to be a three mast steamer!’ ‘Which way headed?’ We decided it was the Alabama.”[8]

The two Federal warships collided, causing damage to both. They briefly made port at Mole Saint-Nicolas, on Haiti’s northwestern coast, to assess damage. Alex Huggins Wilson thought Nereus was there to blockade the ship he still believed in his old age to be a Confederate. Nereus then continued its convoy to Colón, where North Star picked up $465,565 in treasure.

The collision’s damage, however soon took its toll, and in a heavy gale on the return convoy to New York, Nereus was “unable to keep up” and was left behind.[9] It was just one of the many sea stories that every sailor endured in the war, but that rarely make it into the history books.

I would have loved to include Alex Huggins Wilson’s story in my book Treasure and Empire in the Civil War, but alas, the book is already in print, and I unfortunately did not find his oral history until recently. Even though that is not possible, thankfully his story can be shared here.

Endnotes:

[1] Interview of Alex Huggins Wilson, Page 450, Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 11, North Carolina, Part 1, Adams-Hunter. 1936, MSS55715, Manuscript/Mixed Material, Library of Congress.

[2] April 13, 17, 1863, USS Falmouth Logbook, April 1, 1863 – October 28, 1863, Logbooks of US Naval Ships, 1801-1940, Record Group 24: Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798 – 2007. US National Archives; “Marine Intelligence,” New York Times (New York, NY), April 2, 1863; “From the Pacific Coast,” New York Times (New York, NY), April 26, 1863; At the bottom of this link is a paper documenting every single shipment of gold made during the Civil War, what ships carried them, and what Federal naval convoys were offered as protection.

[3] Aspinwall was the name Americans gave to the city of Colón, honoring how ship tycoon William H. Aspinwall was instrumental in helping grow the city. Interview of Alex Huggins Wilson, Page 451.

[4] Interview of Alex Huggins Wilson, Page 451.

[5] Complete Descriptive List of Muster Roll of U.S. Ship Nereus, for quarter ending 30 September, 1864, Muster Rolls of U.S.S. Nereus 1864-1865 and U.S.S. New Era 1863-1865. Muster Rolls of Naval Ships, 1/1/1860 – 6/9/1900. Record Group 24: Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798 – 2007. US National Archives.

[6] Interview of Alex Huggins Wilson, Page 451.

[7] Rinckendorff to Lardner, Sept 12 1864, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Commanding Officers of Squadrons, 1841-1886” Year Range 25 May 1863-3 Oct 1864, West India Squadron, M89, Records Group 45, US National Archives.

[8] Interview of Alex Huggins Wilson, Page 451.

[9] Howell to Welles, September 26, 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 3, 225.

Neil, neat story. For your book’s second edition, perhaps? Or the movie.

The WPA projects can be an amazing source of historical gems. Just last year, in going through hundreds of pages of WPA-funded interviews of residents of Newton County, Mississippi, I found a 1937 interview of a homeowner who described how much she enjoyed the shade of eight oak trees that had been planted 75 years before by a prior owner of the house. That prior owner, M.J.L. Hoye, is my spouse’s Confederate officer ancestor.