A Tea Party at Kernstown: Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Clark on Hunger

ECW welcomes back guest author Danny Brennan.

It was a bright, cool day on March 22, 1862, as the men of the 29th Ohio Infantry rested at Camp Shields, just north of Winchester, Virginia. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Clark spent the day attending to duties, including throwing out a sutler for selling butter that he considered no better than “second rate lard from home.”[1]

His concern with sustenance persisted into the evening as he spoke with Col. Lewis Buckley and Adjutant Comfort Chaffee about “a nice bowl of bread & milk at a farmhouse nearby.”[2] The chat ended abruptly when orders came to move toward the sound of artillery. Combat did not begin for them until the next day, but after the First Battle of Kernstown ended, Clark continued framing his experiences in terms of hunger—for food and for fame.

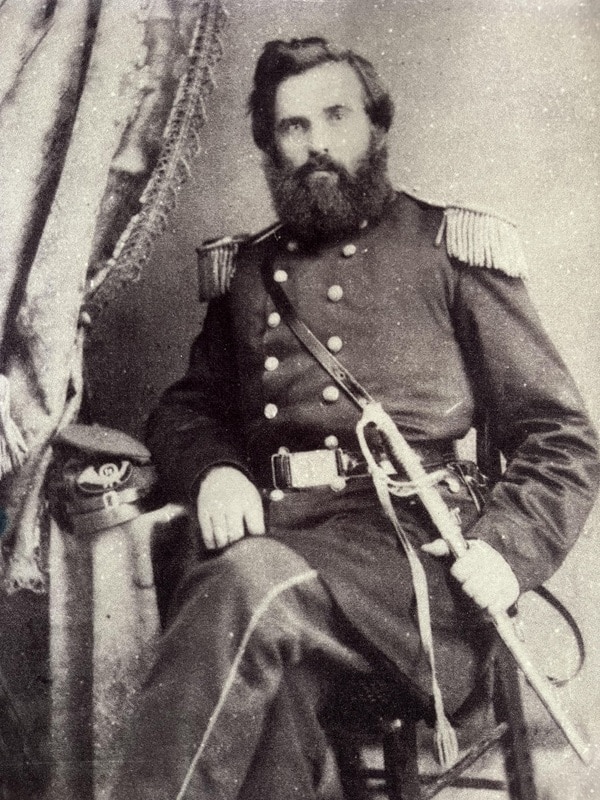

Born in New Hampshire on December 4, 1821, Clark was 40 years old when he fought in the Shenandoah Valley. He and his wife Cordelia “Corrie” Richardson moved to Cleveland, Ohio in 1857. It was there that he joined the 19th Ohio Infantry on a three-month enlistment in 1861, campaigning in what is now West Virginia. His experience led to his appointment as lieutenant colonel of the 29th Ohio in late summer 1861.

I came to know Clark while completing a research fellowship with the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation (SVBF). This opportunity allowed me to use their extensive library filled with valuable sources, including Clark’s letters. A recent addition to the SVBF’s collection, they have been consulted by only a few historians. His correspondence offers valuable insight into the experience of a volunteer officer and survivor of Kernstown, Port Republic, Chancellorsville, and Confederate captivity.

Clark was a prolific writer during his service from May 1861 to July 1863. His letters to Corrie blended diary-style reflection with traditional letter writing, a hybrid form he called “slips.” His system was not intuitive, but it reflected the importance that he gave to writing. Indeed, in his March 22, 1862, entry for Slip 6, Army Services 18, he noted how “my slips of paper & pencil are always handy” from morning to night.[3] His writings frequently referenced hunger; not only physical, but also emotional and psychological.

Clark often expressed a hunger for action. Illness had kept him from fighting at Rich Mountain with the 19th Ohio, and the 29th Ohio had initially only seen minor skirmishes. When comrades of Nathaniel Banks’s army first reached Winchester in early March 1862, he regretted that his men did not play a part in the action, saying, “I feel a little blue over it.”[4] He spent most time idly, and the monotony of army life weighed heavily. “This laying around camp with nothing to do is just killing me,” he remarked.[5]

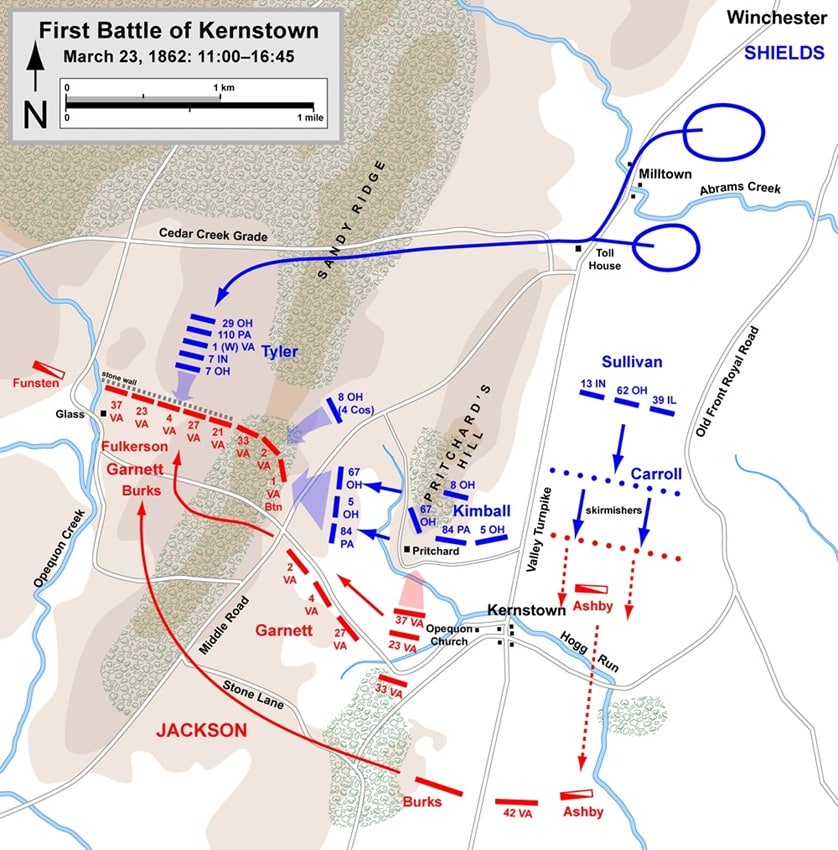

As Clark waited, Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson decided to feed his own appetite for action. His goal was to keep Federal troops away from Gen. Joseph Johnston’s main Confederate force further east. When he learned that Banks might send two divisions away, Jackson seized the opportunity. Faulty intelligence convinced him he was facing only a small force near Winchester as he advanced north to strike Brig. Gen. James Shields’s Federal division.

As a regiment in Shields’s division, the 29th Ohio was in Jackson’s crosshairs. They, along with most of their divisional comrades, missed the first skirmishes on March 22. One person who did experience the oncoming rebel force was the Irish-born Shields, whose arm was broken by an enemy shell. Senior brigade commander Col. Nathan Kimball took over command.

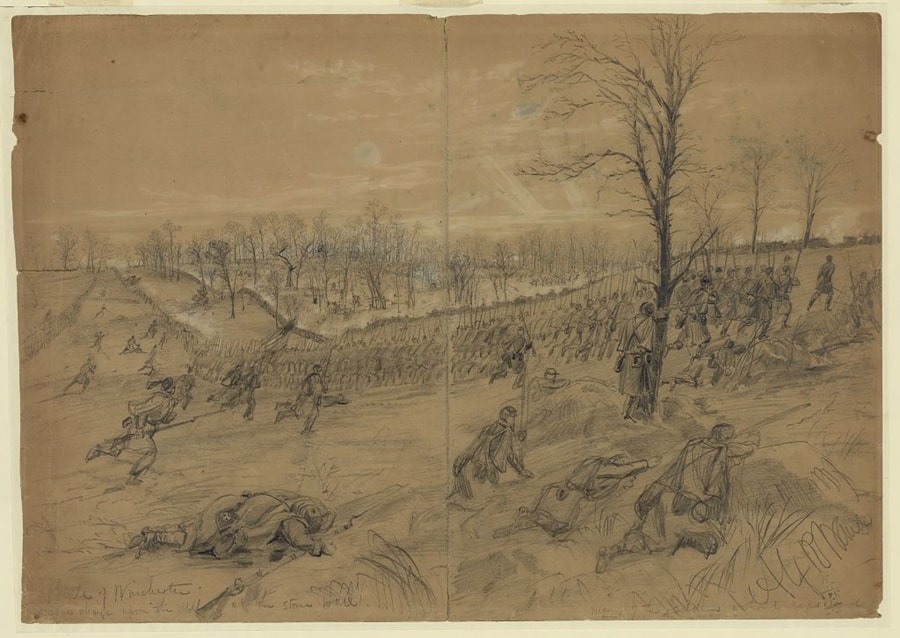

Fighting began in earnest early on the 23rd, forcing most Union soldiers to miss breakfast. Confederates battled Kimball’s troops around Kernstown, a suburb south of Winchester, throughout the morning. As more grayclad soldiers entered the fight, they moved west toward a rise known as Sandy Ridge, attempting to outflank the Union troops. They bolstered their commanding position with a strong artillery presence. Kimball called on Col. Erastus Tyler’s brigade to take the enemy battery and ridge.[6] Around 4 p.m. Tyler sent his men forward, each regiment forming in five compact lines.

The 29th Ohio was the last regiment in line. Still, their experience was harrowing. Jackson’s forces, including the famed Stonewall Brigade, resisted each Federal push. The fighting reached a stalemate. Tyler’s five regiments—in a field and woods—fired against the Virginians behind a stone wall. Clark recalled the terrifying sensory details, including “a good many whizzing sensations in rather close proximity to my head & thug, thug, thug, of the bullets striking against the trees, just as we were emerging from the woods.”[7] Fortunately, none struck him.

As with earlier moments, Clark described the battle through the language of food. His lack of breakfast and lunch, coupled with the hunger that adrenaline rushes tend to bring on, made him sensitive to stories of sustenance.

As he entered the fight, he remembered seeing a member of the 110th Pennsylvania “moving along the column with an old hen in his hand, that he had stolen and killed on the route.” With a curious mix of admiration and disgust, he asked about the man for several days after the action. Once the 29th Ohio began receiving fire, one officer “with a Haversack full of crackers” fell victim to a Confederate shot. The next day, Clark recalled how the man complained about “the rebels careless shooting, that…had made his crackers small as powder.”[8]

Though Jackson’s men were “careless” with crackers, they fought fiercely. Eventually, Kimball’s forces pushed the Confederates away and pursued them for several miles. Clark called the advance “the hardest march we’ve ever had.”[9] To make matters worse, it took two days before provision trains arrived. Once they did, however, the men had “plenty to eat.”[10] In this moment, Clark satisfied both his hunger for food and for action.

Jackson lost the battle, but succeeded in his larger objective: delaying Union forces in the Valley. His appetite for victory was appeased in the months that followed. For the moment, however, Federal forces fought each other to claim credit for the tactical success.

Clark described even these squabbles in culinary terms. When a reporter praised the 110th Pennsylvania for their efforts, many Ohioans expressed their frustration. Their lieutenant colonel challenged them with a metaphor about “the old Lady at a Tea party who has some very poor cake, which she praised highly. On being asked why she praised that and didn’t mention the other, which was decidedly better, she answered, that [the poor cake] needed it the most, [for] the other would recommend itself.” In other words, the actions of the regiment, like the quality of the good cake, spoke for itself. Clark and his men “did not come here for that purpose to make ourselves heroes, but simply to contribute our mite to put down the rebellion.”[11]

Despite his claims otherwise, Clark hungered for some measure of attention. He was disappointed to read a story in the Cleveland Leader that gave “credit…to every Regt of Tyler’s Bridge but the 29th, which was not mentioned at all.”[12] This was Clark’s hometown paper, one that family and friends read. He may not have sought national renown, but local recognition mattered. Until his resignation in July 1863, he paid close attention to the local press, hoping his men would receive their due at the “tea party” of public opinion.

The rich writings of Thomas Clark attest to the fact that hunger was a major part of soldiers’ lives. He felt a psychological appetite for action and attention, particularly in the Ohio press. He also diligently recorded what he ate and described the monotony of camp as well as the horrors of battle in gastronomic terms. His words suggest that, in the chaos of war, soldiers thought as much with their stomachs as with their heads.

Danny Brennan is a PhD student at West Virginia University who works as a seasonal ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park. He is interested in exploring the culture and experience of Union soldiers in war and memory.

Endnotes:

[1] Thomas Clark to Cordelia Clark, March 22, 1862, Slip 6, Army Services 18, Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation (SVBF).

[2] Thomas Clark to Cordelia Clark, March 22, 1862, Slip 7, Army Services 18, SVBF.

[3] March 22, 1862, Slip 6, Army Services 18.

[4] Thomas Clark to Cordelia Clark, March 12, 1862, Slip 5, Army Services 17, SVBF.

[5] Thomas Clark to Cordelia Clark, March 12, 1862, Slip 6, Army Services 17, SVBF.

[6] Gary Ecelbarger, “We Are In For It!”: The First Battle of Kernstown March 23, 1862 (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 1997), 125.

[7] Thomas Clark to Cordelia Clark, April 22, 1862, Slip 1, Army Services 24, SVBF.

[8] March 29, 1862, Slip 1, Army Services 20.

[9] March 22, 1862, Slip 7, Army Services 18.

[10] March 29, 1862, Slip 1, Army Services 20.

[11] April 22, 1862, Slip 1, Army Services 24.

[12] Thomas Clark to Cordelia Clark, April 8, 1862, Slip 1 Army Services 22., SVBF.

This post is making me hungry.

Well written and enlightening. Thanks for sharing!

Nice article! I am just wondering if you are the “Danny” that my Son and I met at Burnside’s Bridge a couple weeks ago? He said he was a Student at WVU and Seasonal Ranger ay Gettysburg. Couldn’t be a coincidence.