Chinese American Civil War Soldiers in Pennsylvania

ECW welcomes guest author Kenny Lin.

For nearly a quarter of a century, I have participated in Civil War battlefield tours from Gettysburg to Shiloh led by various historians and professional guides. In all of that time, I’ve only seen a handful of other Asian faces.

On the surface, that shouldn’t be surprising: Many Civil War enthusiasts have ancestors who served in the Union or Confederate armies, who were overwhelmingly White prior to 1863, when large numbers of United States Colored Troops began fighting for the Union. A few hundred Chinese immigrants were living in the U.S. outside of California at the start of the war, and around fifty are believed to have served.[1] I can’t claim descent from any of them, as my mother and father immigrated from Taiwan in the 1950s and 1960s, respectively. But I suspect that few of my fellow 5.5 million Chinese Americans are aware of their contributions.

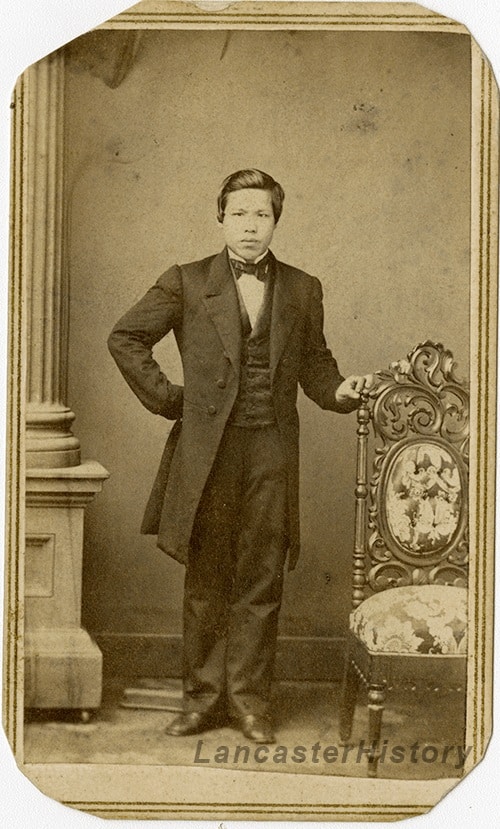

The 2014 National Park Service publication “Asians and Pacific Islanders in the Civil War” highlighted the lives of 16 Chinese Americans who served.[2] One of them, Hong Neok Woo, immigrated from China to Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1855 and became a naturalized American citizen in 1860 (Figure). When the Army of Northern Virginia invaded Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863, Woo enlisted as a private in Co. I, 50th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Emergency Militia. His unit was deployed in Harrisburg and Chambersburg and performed picket duty near Williamsport, Maryland before being mustered out of service on August 15, 1863.[3]

Although Woo emerged from the Civil War unscathed, returning to China in 1864 and living for another 55 years as a priest in Shanghai[4], another Chinese soldier who fought in Pennsylvania was not so lucky. John Tommy, a private in Co. D of the 70th New York Infantry (part of the famed “Excelsior Brigade”), enlisted in the Army of the Potomac in 1861 and was twice captured during the Peninsula Campaign.[5] According to the New York Times, when Tommy was brought as a prisoner before a puzzled Confederate Maj. Gen. John Magruder, the general asked if he was “a mulatto, Indian, or what?”[6] After being exchanged, Tommy was promoted to corporal and participated in the battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville before being killed in action at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863.

Magruder’s confusion reflected a general uncertainty around how to classify Chinese immigrants in an era when the U.S. census had only three racial categories: “Black,” “White,” and “Mulatto.”[7] Joseph Pierce, a Chinese soldier in Co. F of the 14th Connecticut Infantry, manned a skirmish line in Gettysburg on July 2 and defended the Bliss farm on July 3.[8] Unlike Tommy, Pierce was apparently classified and treated as White throughout the war, later participating in the siege of Petersburg and the Appomattox campaign before mustering out after the Grand Review in May 1865. Pierce’s biographer and reenactor, Irving Moy, eventually tracked down Pierce’s five great-granddaughters, who had been unaware of their Chinese ancestry.[9]

At least two soldiers of Chinese descent fought for the Confederacy. Christopher and Stephen Bunker, cousins and members of the 37th Virginia Cavalry Battalion, were the sons of conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker, who traveled with the entertainer P.T. Barnum before marrying two White sisters and settling on a slave plantation in North Carolina.[10] Under Brig. Gen. John McCausland, Christopher participated in the burning of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania on July 30, 1864. He was wounded by Union cavalry one week later and spent the rest of the war imprisoned in Camp Chase near Columbus, Ohio.

Frederick Douglass famously said of African American Union soldiers: “Once let the Black man put upon his person the brass letters ‘US,’ let him get an eagle on his button and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket and there is no power on earth that can deny that he earned the right to citizenship in the United States.” Although they had varied reasons for volunteering for military service, some Chinese Americans were doubtless motivated by the Militia Act of July 1862, which promised citizenship to anyone who served in the Union Army and was honorably discharged.[11] Unfortunately, for Chinese veterans that promise was not fulfilled, as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act blocked them from becoming naturalized citizens[12], and some previously naturalized veterans were later stripped of their citizenship.[13]

The voluminous academic and popular Civil War literature is just beginning to acknowledge the contributions of Chinese and other Asian Americans to the great conflict. Though delayed for several decades, the sacrifices of Chinese American veterans paved the way for the repeal of the Exclusion Act in 1943 and the loosening of restrictions that eventually allowed my parents to immigrate to the U.S. and for their American-born son to develop a lifelong fascination with the battlefields of the Civil War.

Kenny Lin is a family physician, associate program director of the Lancaster General Hospital (Pennsylvania) Family Medicine residency, and deputy editor of American Family Physician. He teaches an elective in Civil War Medicine for medical students at Georgetown University and serves on the Board of Directors of the Lancaster Medical Heritage Museum.

Endnotes:

[1] American Battlefield Trust. Chinese-Americans in the Civil War. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/chinese-americans-civil-war. Accessed 25 October 2025.

[2] Shivley, Carol A., ed. Asians and Pacific Islanders and the Civil War. National Park Service, 2014. https://americasnationalparks.org/asians-and-pacific-islanders-in-the-civil-war/

[3] Worner, William F. A Chinese Soldier in the Civil War. Journal of the Lancaster Country Historical Society 1921;25(3):52-55.

[4] Miller, Emily. The life and accomplishments of Hong Neok Woo. LancasterHistory Blog 26 April 2023. https://www.lancasterhistory.org/hong-neok-woo/. Accessed 25 October 2025.

[5] Ralph, Daniel. A Chinese soldier killed at the Battle of Gettysburg. Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 2 February 2012. https://hsp.org/blogs/hidden-histories/a-chinese-soldier-killed-at-the-battle-of-gettysburg. Accessed 31 October 2025.

[6] China at Gettysburg. The New York Times, 12 July 1863. https://www.nytimes.com/1863/07/12/archives/china-at-gettysburg.html. Accessed 31 October 2025.

[7] He, Angela. “Mulatto, Indian, Or What”: The Racialization of Chinese Soldiers and The American Civil War. The Gettysburg College Journal of the Civil War Era 2019(9):53-75.

[8] McCunn, Ruthanne L. Chinese in the Civil War: ten who served. https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.pdf

[9] Moy, Irving D. An American journey: my father, Lincoln, Joseph Pierce and me. Lulu.com, 2010.

[10] Chew, Roberta. Chinese in the South and in the Confederacy. 1882 Foundation Blog, 29 September 2015. https://1882foundation.org/curriculum-corner/chinese-in-the-south-and-in-the-confederacy/. Accessed 25 October 2025.

[11] Ford’s Theatre Blog. Those who served: AAPIs in the Civil War. 1 May 2023. https://fords.org/aapis-in-the-civil-war/. Accessed 25 October 2025.

[12] National Park Service, Fort Union National Monument. The Chinese patriot. https://www.nps.gov/foun/learn/historyculture/edward-day-cohota.htm. Accessed 25 October 2025.

[13] Choo, Kristin. Tong Kee Hang: a Chinese American Civil War veteran who was stripped of his citizenship. The Gotham Center for New York City History 31 May 2022. https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/tong-kee-hang-a-chinese-american-civil-war-veteran-who-was-stripped-of-his-citizenship. Accessed 25 October 2025.

What a fascinating and under-researched topic. Thank you for highlighting it!