Book Review: The Road was Full of Thorns: Running toward Freedom in the American Civil War

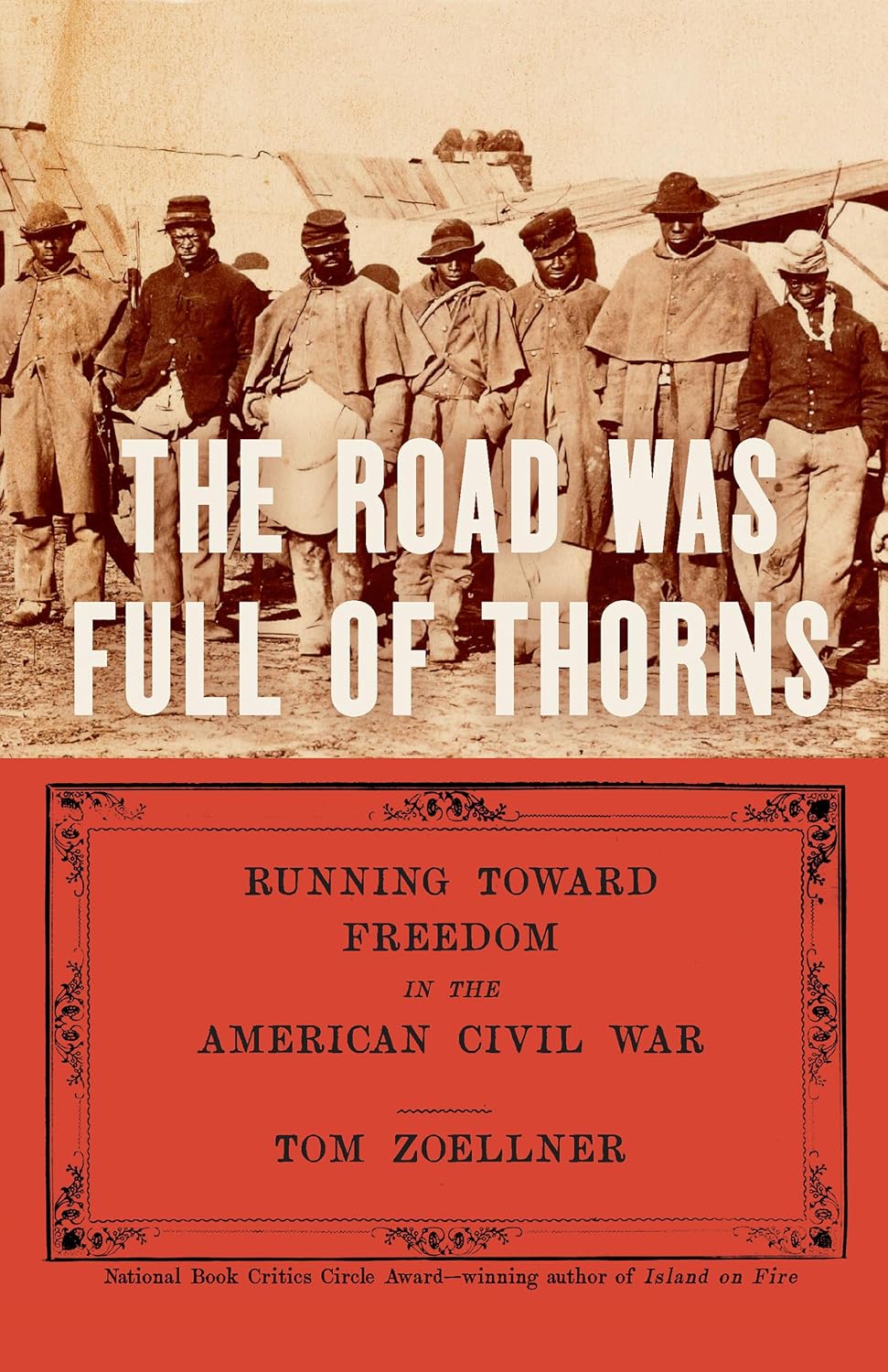

The Road was Full of Thorns: Running toward Freedom in the American Civil War. By Tom Zoellner. New York, NY: The New Press, 2025. Hardcover, 336 pp., $34.99.

Reviewed by Tim Talbott

By the time of the American Civil War enslaved people had been making decisions and taking actions to break the bonds of slavery for over 200 years. However, a pivotal moment occurred on May 24, 1861, when Frank Baker, Shephard Mallory, and James Townsend appropriated a rowboat and set off for Fort Monroe, a Federal-held installation on the tip of the York and James River peninsula. Their agency, and the unwillingness of their enslaver to just let them go, in turn demanded a response from Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, who at the time commanded Fort Monroe.

As most Civil War enthusiasts know, Butler refused the request to return the three on the grounds that the Fugitive Slave Law was now null and void since Virginia has just seceded. Butler instead determined that the men, who had previously been engaged in working on Confederate fortifications, were contraband of war and that he would keep them so that they could not aid the enemy’s cause.

Through the word-of-mouth network that the enslaved referred to as the “grapevine telegraph,” this incident spread across the region and encouraged thousands to make their way to Fort Monroe, or as they came to call it “Freedom’s Fortress,” seeking their permanent liberation.

In his most recent book, The Road was Full of Thorns: Running toward Freedom in the American Civil War, Professor Tom Zoellner details these events and others to highlight the agency that African Americans exhibited during the upheaval of war.

This study joins a growing body of recent scholarship on formerly enslaved refugees, the federal government’s reactions to them, and how their decisions and actions changed not only the policy and course of the war, but also national politics and society.[1]

Along with an introduction and epilogue, Zoellner organizes the book into ten chapters. About one-third of the book discusses the Fort Monroe incident, including a full chapter that covers the long history of slavery in that particular part of Virginia. Ironically, it was at Point Comfort, the future site of Fort Monroe that Europeans landed the first Africans in 1619, and as readers will see, it was at Fort Monroe where American slavery truly began to unravel. While some readers may find this chapter perhaps a bit labored, the significance of the place where this part of the story plays out will be quite intriguing to others.

As one might image, President Abraham Lincoln also makes up a significant part of the book. Zoellner uses Lincoln’s flatboat river pilot analogy to good effect in showing that, as Lincoln himself admitted, events shaped him as much as he shaped events in relation to his efforts to end slavery. Lincoln commented that “The pilots on our Western rivers steer from ‘point to point’ as they call it—setting the course of the boat no farther than they can see, and that is all I propose to myself in this great problem.” (128) The efforts of formerly enslaved people like Frank Baker, Shephard Mallory, and James Townsend changed the minds of people like Gen. Butler, who in turn changed the minds of senators and congressmen who passed the First Confiscation Act in 1861, and the Second Confiscation Act and Militia Act of 1862—the latter of which authorized the president to enlist African Americans—that in turn changed the mind of Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation as a war necessity.

However, as Zoellner persuasively argues: “Without the eighteen-month pilot program of the contraband camps, an emancipation order would have been too frightening for most Northerners to accept. Even with its tangled wording, the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation is even more remarkable for recognizing those efforts of the freed people, which in practical terms meant chancy midnight escapes and potentially fatal disobedience to their masters. Without these uncounted and largely unapplauded efforts, emancipation would never have happened on an accelerated timetable.” (175-176)

While Zoeller makes some factual errors throughout the book as far as a few names, dates, and geography, these are minor quibbles in comparison to the book’s valuable argument and its admirable readability.

The names of Frank Baker, Shephard Mallory, and James Townsend are ones that all Americans should know. The Road was Full of Thorns gives those men and the estimated 800,000 others who took a chance and voted with their feet for freedom their long due proper place in history.

[1] Some other key studies on this subject include: John Cimprich’s Navigating Liberty: Black Refugees and Antislavery Reformers in the Civil War South (Louisiana State University Press, 2022); Chandra Manning’s Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War (Knopf, 2016); and Amy Murrell Taylor’s Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps (University of North Carolina Press, 2018).