“I have always been fond of pies”– Morgan’s Raiders in Clermont County, Ohio

This post is part of a series; check out the previous entry here.

Once General John Morgan and Colonel Basil Duke reunited just after crossing the Little Miami River, they continued southeast on the afternoon of July 14, 1863. In the hot summer sun, most of Morgan’s men rode toward Owensville, Ohio (previously known as Boston, Ohio). The raiders were exhausted, unable to navigate to the small farms they passed—too tired to leave the road, even for food or water. The roads to Owensville were winding and hilly, though the high tree cover offered some reprieve from the blazing sun. No fight occurred while passing through the area, and the cavalry men happily noted that the roads leading away from the small village were straight and flat.

Many of the local women in the area had begun leaving food on tables for the hungry rebels in hopes of keeping them out of their homes. Duke, riding along with the rear guard, spotted some of his men standing near a table that had been placed outside one of the homes. Approaching, he saw fresh pies sitting out, but his men hesitated to eat any, afraid they may be poisoned. Duke reaching down, snagged a piece, and said, “I’ve always been fond of pie.” After realizing Duke had not taken ill from the sweet dessert, his men dug in.

Many of the local women in the area had begun leaving food on tables for the hungry rebels in hopes of keeping them out of their homes. Duke, riding along with the rear guard, spotted some of his men standing near a table that had been placed outside one of the homes. Approaching, he saw fresh pies sitting out, but his men hesitated to eat any, afraid they may be poisoned. Duke reaching down, snagged a piece, and said, “I’ve always been fond of pie.” After realizing Duke had not taken ill from the sweet dessert, his men dug in.

Continuing with his past tendencies, General Morgan once again split his forces. He sent a company southwest towards Batavia while his main column continued towards Williamsburg. Splitting his troops gave better opportunities when foraging for food. The groups covered more ground, creating a larger swath of destruction to northern supply lines in their wake.

Many of the northern civilians kept to themselves with the raiders approaching, only taking time to hide valuable goods that could be easily concealed, content that the Union would make amends for any losses they suffered. Others were not so inclined. For instance, when Solomon Mershon, a resident near Batavia, found that two of his horses had been stolen by the raiders, he went into town to search for the missing animals. After finding one, he challenged the soldier riding upon it to a fair and honorable fist fight. The soldier, weary from his travels, fell easily to the farmer and quitted. Mershon mounted the horse and rode away, listening to the sound of rebel yells in the distance. Whether because of honor or perhaps even humor, the Confederates let Mershon leave unscathed with his steed.

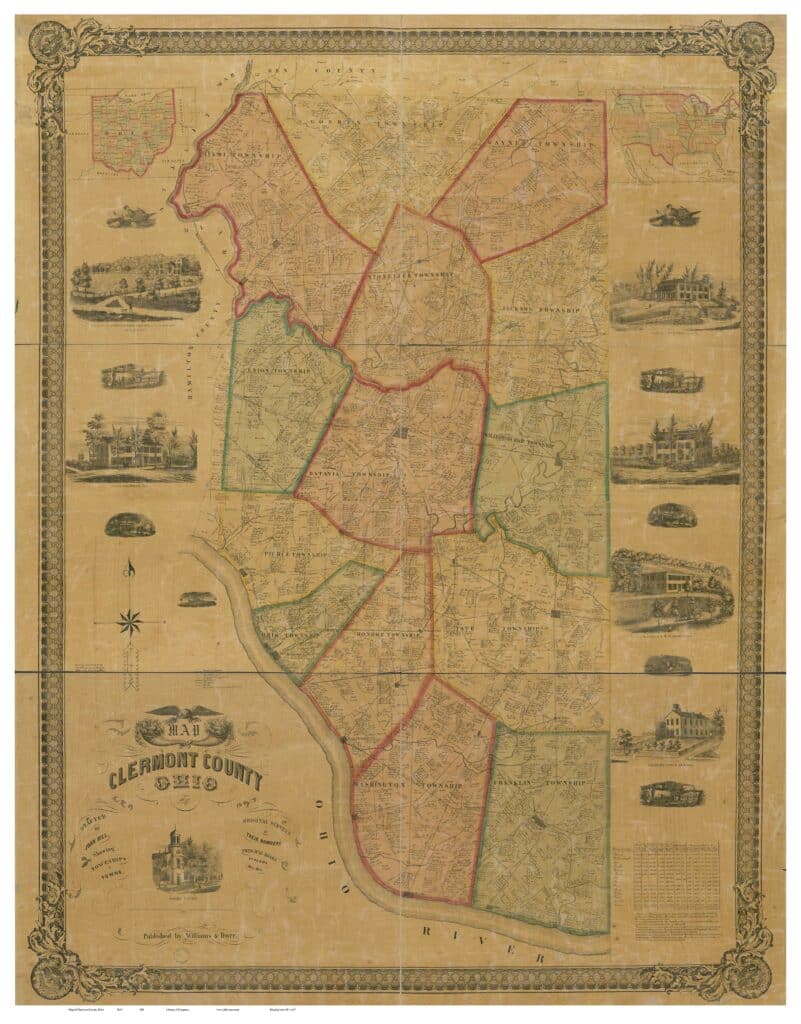

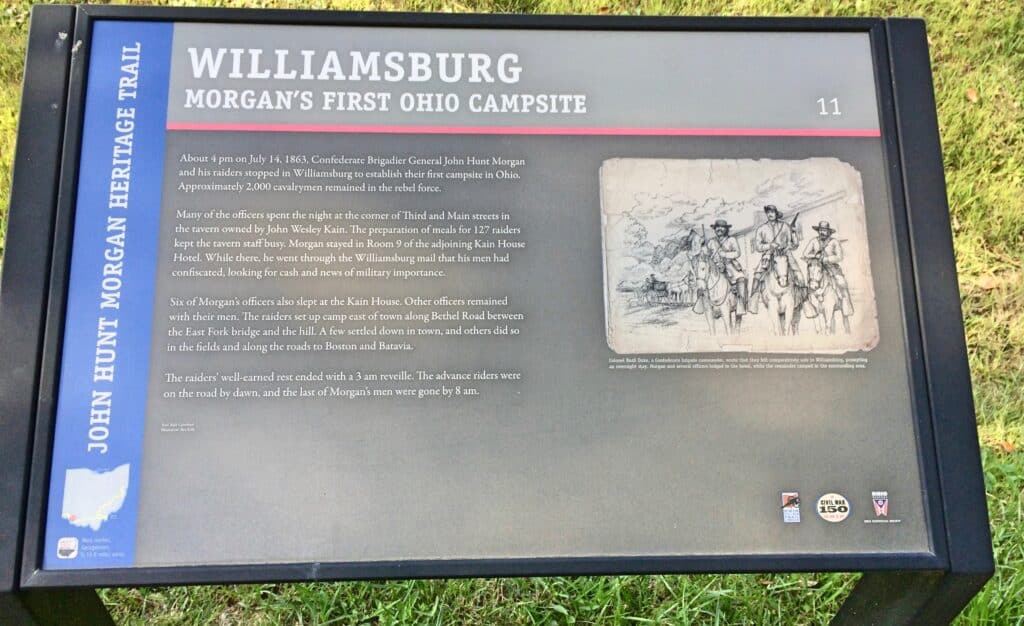

By 4 PM, Morgan’s advance guard rode into Williamsburg. A moderate size town with near 2,000 residents,

Williamsburg was the largest settlement in Clermont County. Here, the raiders got their first full nights’ rest since leaving Tennessee. They had gone from Sunmansville, Indiana to Williamsburg, a 95-mile ride in just over 35 hours. In Williamsburg, General Morgan set up his headquarters and called on the local townspeople to supply his army with food. One of the town’s residents was John Lytle, the brother of Union General William Lytle. Morgan, seeing an opportunity, carved in Lytle’s doorstep: “John Morgan, July 14, 1863, 3,000 men.” Perhaps it was boasting on Morgan’s part, however, since at no time during the raid, did he have 3,000 men with him. By the time he reached Williamsburg, his men numbered around 1,900.

By nightfall on the 14th, all of Morgan’s men were encamped in and around Williamsburg. Though taking the time to rest was imperative for the raiders, the enemy still hovered nearby. Hobson’s troops pursued the Rebel Raiders from Indiana Cincinnati and camped a mere 15 miles away at Newberry.

Before first light dawned on the 15th, both Morgan’s and Hobson’s forces were on the move. Hobson, not knowing the area, requested the help of a local guide, knowing that his proximity to Morgan could be an opportunity to strike and stop the raiders. In a stroke of bad luck, however, Hobson’s guide took him to Batavia first, nearly five miles out of the way and delaying his troops. The Union forces finally arrived in Williamsburg around 1 P.M., 5 hours after the last of Morgan’s men had left.

Back in Cincinnati, the citizens and General Ambrose Burnside still worked towards a way to stop the raiders. The Mayor of Cincinnati, Colonel Leonard Harris, offered his services. Harris had valiantly fought at the Battle of Perryville in Kentucky. However, the battle left Harris weakened and unfit for field service. During his leave, he was seriously injured when bucked from his carriage and broke his hip, forcing him to resign from the army in December 1862. The Daily Cincinnati Enquirer ran the following ad during the morning of July 14, 1863:

CITIZENS: I have said to the General Commanding this department that 3000 mounted men could be obtained in this county to pursue Morgan. … Will you respond to the call? If so, let all who join in the undertaking and can procure a horse, report to my office this morning with two day’s rations. You will be organized and armed at once and will march today. I will go with you. Experienced officers are ready to lead you. Officers not now in service who have a fancy to take the trip after Morgan, will please report to my office, at eight o’clock this morning.

Reportedly, just under 500 “calvary troops” with only 120 horses reported to the mayor’s call, along with 1000 infantry. The Cincinnati Cavalry never left the city. General Henry Judah arrived in the city just before they were to set out. Judah, in his haste to reach Cincinnati from Louisville, had left many of the force’s horses behind. Upon his arrival, he requested from General Burnside the use of any available horses. Burnside accommodated him, ordering the Cincinnati Cavalry, relinquish their horses to General Judah. Still, the people of Cincinnati were invigorated to fight, and soon many volunteer regiments formed to aid in the pursuit of Morgan and his men.

The Governor of Indiana, Oliver P. Morton wrote to Burnside on July 15 requesting that the Indiana troops now in Ohio be sent home.

“The Indiana troops now in Ohio are composed almost entirely of farmers and businessmen, and their presence at home is much needed. I hope you will relieve them from duty as soon as it is consistent with public safety.”

Burnside complied and set word to all commanders that they were to relieve any Indiana Militia of their duty so that they could return home. He stated, “I am satisfied that their services will no longer be needed in this emergency, and their interests at home need looking after.”

From this point forward with Morgan’s forces wholly in the Buckeye State, it would be up to those in Ohio to give chase and stop the raiders. Morgan, for his part, was making a bee line for Buffington Island, which sat along the Ohio and West Virginia border. For the next 12 days Morgan and his men would ride through Ohio’s Appalachian country, trying to reach the relative safety of the south once again.

Great series! What an epic run – I hope you’re working on a book.

Thanks Michael. And I am not currently working on a book, but am hopefully once I finish this series I can pivot it into a book! 🙂

Enjoyable read.

Thanks David! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

This whole foray is an amazing story: 2000 rebel horsemen on a 1000 mile ride in Indiana and Ohio … thanks for the details about pies and fist-fights over stolen horses … they make the story … only in our civil war would that happen … thanks for telling this terrific tale!

You are very welcome! This whole story is very near and dear to me as I grew up in Southeastern Indiana. My grandparents are buried on the same land that Morgan and his men stopped at outside of Sunman (Sunmansville as it was called in 1863), IN.

Great article and thanks for sharing it! I discuss Morgan’s (well, really Duke’s) fight against Col. Neff’s small number of Union volunteers and invalids from Camp Denison at Miamiville, Ohio as part of a chapter in my upcoming book on the Invalid Corps/Veteran Reserve Corps. You might find that interesting, too.

I will definitely have to check that out!! Thanks for letting me know. I believe it was 1 or 2 posts ago that I covered Camp Denison, but I didn’t go into too much detail. 🙂

Caroline, agree with the prior poster – a very enjoyable read, filled with human interest aspects. I look forward to future installments on Morgan’s journey.