Ulysses S. Grant, from Semicentennial to Semiquincentennial

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back our friend Ben Kemp. Ben is the operations director at Ulysses S. Grant Cottage National Historic Landmark atop Mt. McGregor in Wilton, NY. The following article appears courtesy of the Friends of Grant Cottage, which originally published the article in its end-of-year newsletter. It appears here by invitation from our editor in chief.

————

1892)

In the summer of 1885, as a dying Ulysses S. Grant sat at the Eastern Lookout on Mt. McGregor in his final days, he looked out on a landscape where the United States was forged. Within the expanse of valley, hills, and mountains in view were pivotal sites of the American War for Independence with names like Hubbardton, Bennington, and Saratoga. Grant took pride in the role his own grandfather Noah had played in the struggle of the previous century. A reminder rising just barely visible ten miles to the east was a 155-foot-tall stone obelisk near the Hudson River. The Saratoga Battle Monument was completed just two years prior to commemorate the pivotal victory over the British there in 1777.

Grant, as general two decades before, had joined the struggle to maintain that union during the Civil War. Grant would state that he was “resolved to perform my part in a struggle threatening the very existence of the nation. I performed a conscientious duty, without asking promotion or command, and without a revengeful feeling toward any section or individual.” On August 4th, 1885, the sound of cannons was heard in the valley, just as they were back in 1777; this time, however, it was not the patriots establishing a fledgling nation, but the servicemembers tasked with protecting it and honoring the life of one who dedicated so much of his life to his nation.

When Grant was just a young boy in Georgetown, OH in 1826, two of the three remaining signers of the Declaration of Independence died simultaneously on the 50th anniversary. Thomas Jefferson, who penned the famous document, wrote confidently shortly before his death, “In short, the flames kindled on the 4th of July 1776 have spread over too much of the globe to be extinguished by the feeble engines of despotism. On the contrary they will consume these engines, and all who work them.” The nation celebrated “America’s Jubilee” with parades and ceremonies awakening an appreciation for their national heritage and inheritance.

While navigating the difficult years after the Civil War when divisions still lingered, President Grant took part in commemorating the centennial of the re-united nation. In 1870 the U.S. Congress established Independence Day (July 4th) as a federal holiday, though it had been celebrated in a somewhat partisan manner for decades. That year, as the nation began to coalesce around its founding, President Grant attended one of the largest Independence Day celebrations in the U.S. held at Woodstock, CT.

Understanding that not all Americans were easily enjoying the privileges of citizenship due to prejudice, President Grant committed that the federal government would put “forth all its energies for the protection of its citizens of every race and color.” He noted that “The present difficulty, in bringing all parts of the United States to a happy unity and love of country grows out of the prejudice to color. The prejudice is a senseless one, but it exists.”

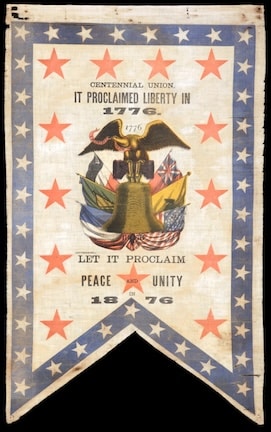

As preparations began for the centennial in 1872, newly re-elected President Grant wrote: “This celebration will be looked forward to by American citizens with great interest, as marking a century of greater progress and prosperity than is recorded in the history of any other nation…”

In April 1875 the President attended the centennial ceremonies at Lexington and Concord, MA where the first shots of the Revolution rang out. Later in the year he spoke to a veteran’s reunion Des Moines, IA imploring his fellow citizens to continue to safeguard their inheritance:

“Now, in this Centennial year of our national existence, I believe it a good time to begin the work of strengthening the foundation of the house commenced by our patriotic forefathers one hundred years ago at Concord and Lexington. Let us all labor to add all needful guarantees for the more perfect security of free thought, free speech and a free press, pure morals, unfettered religious sentiments and of equal rights and privileges to all men, irrespective of nationality, color or religion.”

In early May 1876, President Grant opened the sprawling Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia which he had supported the funding of. In his remarks to a crowd of more than 100,000, Grant expressed pride in the achievements of the country, but also “an earnest desire to cultivate the friendship of our fellow members of the great family of nations,” who were invited to take part in the exposition. The event, featuring 200 buildings, showcased the incredible progress the nation had made in its first century with technological marvels like the Corliss Steam Engine, which the President started along with Emperor Pedro II of Brazil. With 10 million visitors and 35 countries participating, the event was truly a coming together in recognition of American independence and ingenuity.

Although the event was geared toward instilling fresh civic pride and patriotism, it nonetheless showcased the social and economic divides of the era. Grant acknowledged the challenges of extreme wealth inequality stating that “Money . . . not held in as few hands . . . is what we want to see in a republic.” To make sure everyone had an opportunity to take part in observing the centennial, President Grant encouraged all communities throughout the nation to compile their own local histories.

It would be Grant’s decision to have the original Declaration of Independence displayed at the exposition in its deteriorated condition along with efforts by the Sons of the American Revolution that would help spur the creation of the National Archives to help preserve the history of the nation. Grant reflected on the cornerstone of a functioning system of democratic government in 1875 stating that “the education of the masses becomes of the first necessity for the preservation of our institutions. They are worth preserving, because they have secured the greatest good to the greatest proportion of the population of any form of government yet devised.”

As the July 4th observance of the Declaration of Independence drew near, President Grant issued a proclamation that “the Centennial Anniversary of the day on which the people of the United States declared their right to a separate and equal station among the Powers of the Earth seems to demand an exceptional observance.” The proclamation took on a religious tone as he acknowledged the vital role of “Almighty God” in the establishment, preservation, and progress of the nation. The President also had personal family connections to the date as his daughter Nellie was born on the patriotic date in 1855. Grant is said to have playfully convinced his little girl that the observances, including fireworks, were in celebration of her birth.

The need for national unity was never more apparent then just after President Grant closed the Centennial Exposition in November. The contested 1876 election between Rutherford Hayes and Samuel Tilden devolved into a bitter partisan mess which laid bare the prejudices and divisions that still lingered. The compromise which was struck may have preserved order at the time, but would prevent many citizens from exercising their constitutional rights for generations, effectively preventing them from being full participants in the union.

When the sesquicentennial (150th) anniversary of the Revolution came around in 1926, West Point graduate and grandson of Ulysses Grant, Lt. Col. Ulysses Grant III oversaw the parks in Washington DC where observances would be held. Oddly enough President Calvin Coolidge was depicted alongside George Washington on a coin minted by the U.S. Treasury to raise funds for the Sesquicentennial Exposition in Philadelphia, despite a tradition of not featuring living politicians on American currency. The Treasury grossly overestimated demand for the coin and more than 850,000 of the one million produced were melted down afterwards, perhaps symbolic of the distaste for what some Americans perceived as monarchical imagery.

As a young child, Grant III had been with his grandfather during those fateful days on Mt. McGregor some four decades before and was the second family member to be born on the 4th of July (1881). A proponent of historical preservation, Grant III was a member of The Order of the Founders and Patriots of America and the Sons of the American Revolution from which he received the Gold Good Citizenship Medal for “Outstanding and unusual patriotic achievement and service of national or international importance.” The medal depicted a Revolutionary War Minuteman on the front and the following on the reverse:

“Our inspiration is from the past,

Our duty is in the present,

Our hope is in the future.”

At Mt. McGregor in May 1926, American veterans and others gathered near Grant Cottage to sing patriotic songs and give stirring speeches. The following year a massive 70ft high flagpole and oversized flag were dedicated at the Eastern Overlook on the mountain, a symbol of pride and unity to be seen for miles by residents and travelers in the valley below.

In 1976, the United States was once again commemorating its past and those who had helped achieve and preserve the nation. George Washington was posthumously promoted to General of the Armies (a rank later posthumously awarded to Ulysses Grant in 2022). In the light of expanded interest in the nation’s history, Grant’s Boyhood Home in Georgetown, OH was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

At the time of the centennial, Mt. McGregor was in a period of transition and uncertainty. At the same time, the legacy of U.S. Grant was slowly fading from American memory. Grant Cottage was closed briefly in the early 1970’s (though the resident caretaker continued to provide tours to visitors) but was back open to the public seasonally in time for the Bicentennial. The neighboring facility built as a sanitorium on the mountain was slated to be demolished to become state park land only to instead be controversially repurposed as a state correctional facility by the end of the year.

The last surviving member of the Grant family member that was present in 1885, Julia Grant Cantacuzene (born 1876), died the previous October, marking the transition from living memory to memory. Despite hardships over the ensuing decades, Grant Cottage would prevail and remain open into the 21st century.

As the nation now looks to its 250th Anniversary in 2026, Grant Cottage Historic Site is preparing to honor the founding of the nation and help engender historic appreciation, civic pride, and perhaps most importantly, recapture a sense of unified purpose. Through special programs and new interpretive experiences Grant Cottage seeks to connect visitors with a national identity forged two and a half centuries before. Just as the flag and the Declaration of Independence are considered symbols of national pride and unification, so is the figure who spent his career up to his final days trying to encourage national unity. As visitors gaze out over the view from the Eastern Outlook, just as Grant did 140 years ago, they can reflect upon, just as he did, the privileges and progress that were achieved through patriotism and unity of purpose. In his first annual message, President Grant evoked the words of George Washington in his farewell address that we must remember, honor, and support all those who have been part of maintaining “that unity of government which makes us one people.”