Solferino: A Not Well-Known Rehearsal for Our Civil War

ECW welcomes back guest author Joseph Casino.

In the summer of 1859 while John Brown was at home in North Elba, New York, plotting his seizure of the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry and Capt. George Pickett was becoming involved in a possible war with Great Britain over a murdered pig on San Juan Island, momentous events were occurring in Europe which prefigured some of what was to come a few months later in the United States.

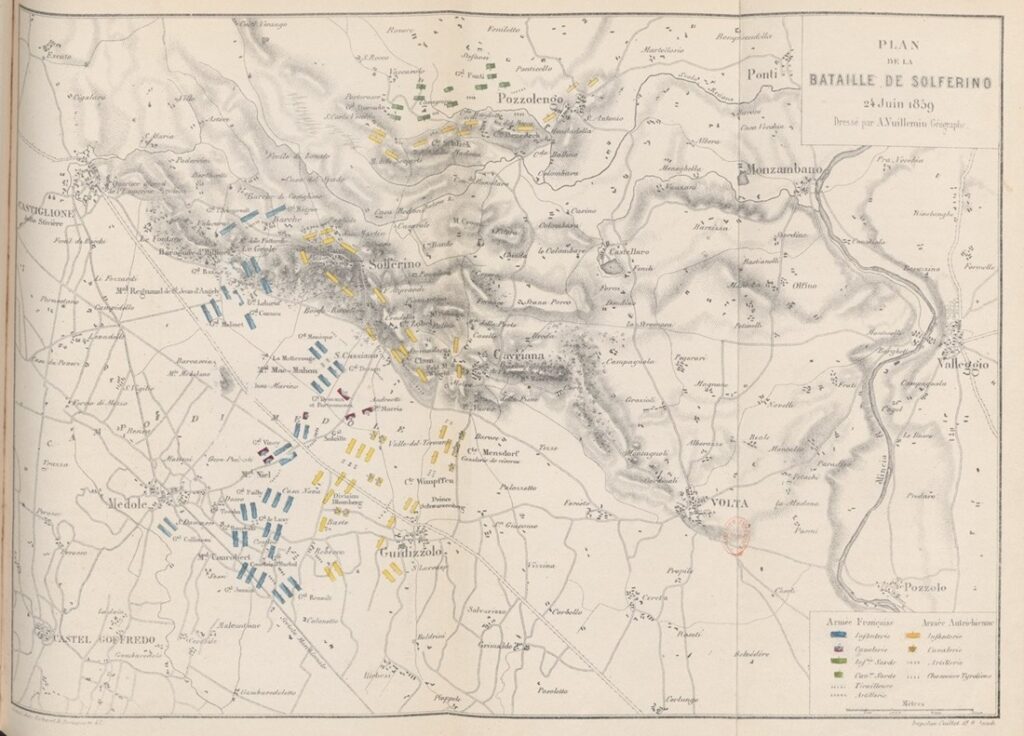

One of the largest and bloodiest battles in modern history, the battle of Solferino, was fought in the Lombardy region of northern Italy on June 24, 1859, as part of the Second Italian War for Independence. In a single day, about 263,000 soldiers from three armies (French, Piedmontese, Austrian) suffered nearly 39,000 total casualties. That would make Solferino bigger than the three-day battle of Gettysburg (165,000 engaged), and more costly in human life than the one-day battle of Antietam (22,700 casualties).[1] However, scant attention has been paid to this battle, except in statements that express horror at its monumental brutality, or as a prelude to Henri Dunant’s campaign leading to the creation of the International Red Cross.[2]

Solferino’s relative invisibility is understandable, sandwiched as it is between much better advertised and photographed fights. As Sonya de Laat observed, “Solferino has not had the same lasting impact on popular memory as the Crimean War that preceded it or the American Civil War that would shortly follow. The dearth of Solferino photographs compared to the wealth of those produced in the other two battles [wars] is a likely contributing factor to Solferino’s conflict being all but forgotten outside of Italy or humanitarian action circles.”[3]

While the Second Italian War for Independence lasted only eight weeks, its significance for the American Civil War far outweighed its temporal brevity. It saw the French Emperor, Napoleon III, rise to the height of prominence by his presence on the battlefield of Solferino, leading to his desire to restore French power in North America (Mexico) while the Americans were busy killing each other in their civil war.[4] The battles of the Italian War of 1859 were the first where rifled artillery were used on a large scale. At Solferino, the French 4-pounder rifled cannon had an accurate range of more than 3,000 yards, nearly twice the range of the Austrian smoothbores. Both armies were also equipped with new rifled muskets, the French Minié and the Austrian Lorenz, similar to those which would cause such enormous casualties a few months later in the United States.

The war in Italy also saw an early use of balloons for aerial reconnaissance and French use of railroads to execute a wide flanking assault on the Austrian right flank, both of which would see increased employment in the American Civil War.[5] Solferino was the first battle reported on by the newly created New York Times.[6] And, despite general ignorance of Solferino in the United States, the unique uniforms and the assault tactics of the French Zouaves were already familiar among American military men. The French at Solferino relied on aggressive infantry columns to break Austrian defensive lines.[7] Future Civil War general, Maj. Philip Kearny, participated in one assault on those lines.[8] The Austrians kept to defensive positions at Solferino’s heights, but it was really their lack of training that caused them to ignore the defensive potential of their rifled muskets against French assaults.[9]

Much of the fighting was uncoordinated and bloody.[10] Prefiguring the actions of Jackson’s men at Second Manassas, Henry Dunant described “The fury of the battle was such that in some places, when ammunition was exhausted and muskets broken, the men went on fighting with stones and fists.”[11]

However, the multi-ethnic character of the armies and intense nationalistic hatreds meant it was fought with a viciousness rarely witnessed in Civil War battles. Dunant added, “The Croats finished off every man they encountered; they killed the Allied wounded with the butts of their muskets; the Algerian sharpshooters too, despite all their leaders could do to keep their savagery within bounds, gave no quarter to wounded Austrian officers and men, and charged the enemy ranks with beast-like roars and hideous cries.”[12]

The battle lasted over sixteen grueling hours in intense heat, ending when the Austrians were forced to yield their strong defensive positions and retreat to the even more formidable fortresses of the Quadrilateral.[13] The Austrian army suffered 21,737 in killed, wounded, and missing. The French-Piedmont armies won a tactical, but costly victory. They lost 17,191 in killed, wounded, and missing.[14]

How does Solferino measure up in terms of casualties when compared to major Civil War battles? We may never know precisely. Reports of numbers engaged and losses suffered vary widely. For a one-day battle, Solferino’s reported casualties certainly outweigh those at Antietam, the single bloodiest day in American military history. However, a rough estimate places Solferino casualties at 14.7 percent of those engaged, compared to 21.4 percent for Antietam.

What is even more surprising is that the force that did most of the attacking at Antietam (Union) seems to have suffered 20 percent casualties while the defending force (Confederate) suffered 23 percent casualties.[15] The same is true for Solferino. The attacking force (France-Piedmont) suffered 10 percent casualties, while the defending force (Austrian) suffered 11.5 percent casualties. To the Austrians, and to many American military leaders, offensive shock tactics seemed to prevail over defensive fire power. That assumption would lead to the stiff casualties in several battles of the Civil War and in the Austro-Prussian War that followed in 1866.[16]

Joseph J. Casino has been an adjunct professor of history at Villanova University since 1978 and serves on the Board of Governors of the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia.

Endnotes:

[1] H. C. Wylly, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino, 1859 (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1907), 148. There were bigger and/or bloodier battles during the Napoleonic Wars (Waterloo, Borodino, Leipzig).

[2] It was the size of the destruction of human life at Solferino, and the abysmal state of care for the wounded and dying soldiers after the battle that has attracted the most attention. Henri Dunant would write after the battle: “When the sun came up on the twenty-fifth, it disclosed the most dreadful sights imaginable. Bodies of men and horses covered the battlefield; corpses were strewn over roads, ditches, ravines, thickets and fields; the approaches of Solferino were literally thick with dead. The fields were devastated, wheat and corn lying flat on the ground, fences broken, orchards ruined; here and there were pools of blood.” Henri Dunant, A Memory of Solferino (Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross, 1986), 11.

[3] Sonya De Laat, “The Camera and the Red Cross: ‘Lamentable pictures’ and Conflict Photography Bring into Focus an International Movement, 1855-1865,” International Review of the Red Cross 102, no. 913 (2020): 432. The only two surviving photographs which portray the carnage that occurred during the Solferino campaign are one stereograph which shows a long line of wagons taking the Solferino wounded back to makeshift medical facilities in the town of Brescia and another which shows piles of bodies awaiting burial in the cemetery at Melegnano.

[4] Solferino was the last battle where the armies were led personally by the monarchs of their respective nations (Napoleon III, Victor Emmanuel II, and Franz Josef I).

[5] The balloon assent by Eugène Godard (1827-1890), however, conveyed the mistaken impression to the French that there were no considerable organized Austrian troops to be encountered between Magenta and Solferino. Patrick Turnbull, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985), 119; Richard Holmes, Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 2013), 98, 233.

[6] Jonathan Marwil, “The New York Times Goes to War,” History Today 55, no. 6 (June 2005): 47.

[7] Wylly, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino, 1859, 220-23.

[8] Kearny served on the staff of French General Louis-Michel Morris. Robert R. Laven, Major Geneal Philip Kearny: A Soldier and His Time in the American Civil War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2020), 46-47; William B. Styple, “Philip Kearny: An American soldier’s gallant fight in the Battle of Solferino,” https://dragoon1st.tripod.com/cw/files/kearny_solferino.html.

[9] Austrian grand strategy had emphasized strong fortified defensive positions and fire power over mobility and communications. Ignoring the poor leadership and weak training of its troops at Solferino, their defeat in 1859 caused a major Austrian reversal in that doctrine that served them equally unwell in the next war with Prussia in 1866. Geoffrey Wawro, The Austro-Prussian War: Austria’s War with Prussia and Italy in 1866 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 30-32.

[10] Arnold Blumberg has described the war of 1859 as “a carefully planned accident,” and so were battles like Solferino where the contending armies did not know of the other’s whereabouts until the evening before. Arnold Blumberg, A Carefully Planned Accident: The Italian War of 1859 (Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press. 1990), 25, 83.

[11] Dunant, A Memory of Solferino, 6.

[12] Dunant, A Memory of Solferino, 6.

[13] aroldCarmicahel Wylly’s verdict on the Austrian defeat was thatCThe Quadrilateral was a square-shaped territory eastward of the Mincio River, bounded by the heavily-fortified towns of Peschiera, Verona, Legnano, and Mantua.

[14] Wylly, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino, 1859, 166-67. Reinterments in 1870 suggest that deaths were actually double the official reports of the time. Simon Bradley, “Solferino: The Bloody Birth of a Nation,” (2009), https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/demographics/solferino-the-bloody-birth-of-a-nation/3664.

[15] Only 61,000 of the total Union forces of 80,000 were actually engaged at Antietam.

[16] Richard Brooks, Solferino 1859: The Battle for Italy’s Freedom (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2009), 89.

It’s hard not to conclude that Kearny was probably one of, if not the most, experienced officer in the Union Army. Certainly it’s hard to think of many others who’d experienced a battlefield containing hundreds of thousands. Kearny had seen Mexico, Indian-Fighting, Algeria and the Franco-Austrian War.

Glad to see these wars related given their proximity in time if not location

Very interesting! I was unaware of this battle. It’s incredible how many men were involved at the time. I was looking forward to hearing more about Pickett and the pig though

Being interested in both the American Civil War and the 19th century writ large, I like how this article incorporates the former into the broader context of the latter.

An excellent article. The only thing I really knew about this battle was Kearney’s participation.