Robbers Road and Sutlers’ Scrip: Shopping with the Soldier

ECW welcomes back guest author Mike Busovicki.

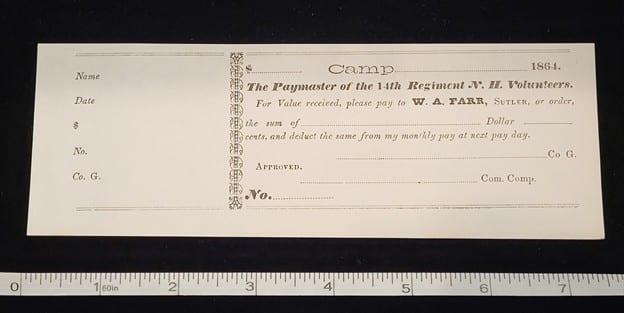

Sutlers–private operators of the Army’s version of a travelling general store–operated in their own realm separate from the military supply chain. Catering to the soldier, they aimed to add some comforts to camp life – at a price. The sutler offered non-regulation items the quartermaster could not, or would not, provide. These products included razors, tobacco, watches, sewing kits, stamps, ink, boot polish, brushes, newspapers, envelopes, books, canned food and more. When available, they offered fresh fish, oysters, fruit, vegetables, and dairy. Pies were very popular, even if their content was sometimes suspect. Most desirable was coffee, though if regimental leadership had a lax enough policy about it, alcohol could be had as well.

While sutlers had a reputation for price-gouging, prices reflected the risk of bringing the goods (and themselves) to the front lines in addition to scarcity. Complain as they might, a soldier knew if they refused to pay the inflated costs, someone else would.[1]

Army regulations allowed sutlers to be appointed at the rate of one for every regiment, corps, or separate detachment by the commanding officer. Sutlery expanded exponentially along with the growing armies. State militias allowed commanders considerable leeway in appointing (or at least permitting) merchants to sell goods to the men. Mustered in with their own uniforms and weapons, sundry goods were never a priority or logistical reality. Unfortunately, if officer appointments were politically or financially connected, then those commanders were more likely to be similarly motivated when approving sutler and other contracts.[2]

To say there was friction between sutlers and the military is an understatement. The sutler, who was a civilian and not an officer, held no authority over soldiers. They bristled at regulations and the possibility of military punishment. Some officers viewed sutlers as another opportunity to leak military secrets or movements, degrade combat readiness, and spread rumors. Still, the demand for convenient goods, a lack of alternatives, and overtaxed quartermasters meant no real competition for the sutler. While often painted as parasitic, the incentive to maintain lucrative appointments and keep their captive market satisfied probably self-regulated sutlery more than the army would admit. Their individual legacies deserve better than being known simply as con artists.

The sutler obtained goods from a variety of contractors and local markets, but if he sold substandard product, it was the sutler and not the manufacturer who was the target of soldiers’ ire and retaliation. Meanwhile, the officers overseeing sutlery operations could be equally unscrupulous, manipulative, or even complicit in price-fixing. The sutler compensated by adjusting prices due to spoilage, loss, or theft, an endless cycle of everyone seeking advantage where they could.

The navy didn’t fare much better. While there was better access to goods in port, long stretches of blockade time or riverine warfare deep in enemy territory along the Mississippi, Cumberland, and Tennessee rivers did not allow for frequent resupply. Ships could be visited by “bumboats,” or merchants that might row up to a ship or even be allowed on board to offer their wares. Various sutler ships also operated on the rivers as a more expedient means of transport. But this system was unreliable and suffered the same criticism about substandard quality and overcharges.[3]

Because unregulated prices were the focus of most complaints, on March 20, 1862 Congress implemented legislation on two significant aspects: First, the sutler could collect no more than one-sixth of the soldier’s monthly pay to settle accounts (the issue of junior enlisted getting into credit debt is not a new concern). Second, though sutlers were still appointed by the regimental staff, prices were approved by a panel of brigade-level officers. Both measures, accompanied by regular inspections, decreased exploitation. Improving troop welfare was essential as calls for a negotiated peace rose in the north, and abuses of the fighting men would no longer be tolerated.[4]

Though non-combatants, sutlers still risked capture, and both sides took sutlers and their clerks as prisoners. While wagon-trains of supplies had obvious value, depriving the enemy of logistical support reduced combat effectiveness and morale. Initially, prisoner exchanges also included a swap for sutlers or others in similar positions. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton produced an agreement dated September 25, 1862, that sutlers would be exchanged in accordance with existing standards. But this broke down for two reasons: the north’s attritional policy of limiting manpower returning to the south and disagreement over which personnel constituted “similar positions.” The Confederates demanded various agents in return, while those in the same occupation appeared to be Stanton’s original intent. The south unsuccessfully argued that these non-combatants had equal status. Eventually, with fewer sutlers to exchange directly, the requisite personnel to continue the process didn’t exist.[5]

The most under-reported aspect of sutlery was that even the most infamous prison camps, including Andersonville and Elmira, were intermittently serviced by sutlers. As both sides adopted increasingly cruel and retaliatory punishment, Stanton ultimately prohibited trade with prisoners in December 1863. He later relented somewhat when it was clear the harsh winters exacerbated the need for basic clothing and hygiene needs, and the federal government could benefit from the commercial venture. In the south, Confederate guards were willing to trade food for manufactured goods, jewelry, and greenbacks. The Federal prisoners used Confederate dollars to purchase whatever was available from the sutler.[6]

The sutler’s government-sanctioned monopoly didn’t last. By 1866, enough complaints of exorbitant charges and predatory dealers led to the abolition of the sutler system. The Army’s far-flung outposts still faced procurement challenges and authorized “post traders” were operating by 1867 on a similar basis.[7] Amazingly, the post-trader system was a step in the wrong direction. This motley assortment of retailers was not subject to the Civil War era congressional regulations, and traders did considerably more business (and damage) through alcohol sales.[8] In 1876, Secretary of War William Belknap resigned ahead of his certain impeachment for bribery involving the appointment of post traders, and traders were forced to pack up shop by 1893.

Assistant Adjutant General Theodore Schwan, tasked by the army to improve non-regulation commerce in camps while reducing carousing and other troubles, established co-operative base canteens. These were more likely to encourage recreation (billiards, cards, and other games), provide necessary goods at reasonable prices, and were co-located with the base library or another administrative building.[9]

Based on the success of Schwan’s model, in 1895, General Order Number 46 created the “Post Exchanges”: stores operated under War Department oversight. The post or base exchange (commonly referred to as the “PX”, “NEX”, or “BX” in modern times) also provided access to sports or exercise facilities and gymnasiums.

Over the last 131 years, the exchange system has evolved into the modern comprehensive on-base shopping and customer-focused benefit enjoyed by Active and Reserve personnel, Veterans, and their families. In addition to discounted or tax-free shopping, today’s exchange system also supports community and MWR (Morale, Welfare, and Recreation) programs, wherever our military serves.[10]

Mike Busovicki is an Iraq War Infantry Veteran. He evaluates disability claims for the Department of Veterans Affairs and holds a master’s degree in public and international affairs.

Endnotes:

[1] John D. Billings, Hardtack & Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life (University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 217-230; Alfred J. Tapson, “The Sutler and the Soldier,” Military Affairs Vol. XXI, No. 4 (Winter 1957): 175-180.

[2] Francis A. Lord, Civil War Sutlers and Their Wares (Thomas Yoseloff Ltd., 1969), 17.

[3] The Navy and Marine Corps Exchange (NEX and MCX), “Our History”, https://www.mynavyexchange.com/nex/enterprise-info/our-history?srsltid=AfmBOooL0sddohTo3PCLhdgVZW9-5HY89WkVXBvDcGA4NL3W2u_IBNho; “NEXCOM Celebrates 70 Years of Serving the Navy Family”, Navy.mil, March 31, 2016, https://www.navy.mil/DesktopModules/ArticleCS/Print.aspx?PortalId=1&ModuleId=523&Article=2260735; Lord.

[4] Tapson.

[5] Lord.

[6] Billings; Lord.

[7] Philpot, Robert, “Evolution of the Exchange – Post Traders and Canteens”, The Exchange, https://www.theexchangepost.com/2025/07/18/flashbackfriday-evolution-of-the-exchange-post-traders-and-canteens/.

[8] David M.Delo, Peddlers and Post Traders: The Army Sutler on the Frontier (Helena: Kingfisher Books, 1998), 152; Megan M.S. Nishikawa, “Go, Then, to the Front as Temperate Men:” The U.S. Army, Temperance Advocacy, and Lessons Learned to 1873”, Doctoral Dissertation, Liberty University, Lynchburg, TN, 2023, https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5883&context=doctoral; Philpot.

[9] Delo; Frederick J. Hannah, “Army and Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES): Its Relevance”, Strategy Research Project, U.S. Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, PA, 2011, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA559976.pdf; Philpot.

[10] The Army and Air Force Exchange (AAFES), “The History of the Exchange”, https://www.aafes.com/TimeLine/#exchangetoday; Hannah; Philpot.

I always enjoy reading Mike’s articles. I find them informative, interesting as they expand my knowledge of areas of the Civil War I’m not familiar with.