“A Continuous Ovation”: Pea Ridge Veterans and the Response to Bragg’s Kentucky Campaign

Uncertainty and fear gripped the Ohio River valley in the late summer of 1862. Confederate armies under Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith were advancing north, marching ever deeper into the border state of Kentucky, towards the Ohio River and the Federal heartland beyond.

Many Kentucky civilians enthusiastically welcomed the Confederate armies. Such sentiment was strongest in the Bluegrass region, the prosperous agricultural heartland of Central Kentucky, anchored by the state capital at Frankfort and the bustling town of Lexington. Captain E. J. Ellis of the 16th Louisiana observed that “the people of this section are nearly all secessionists – They received us with the wildest demonstration of delight.”[1] Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee recollected with some nostalgic flourish “how gladly the citizens of Kentucky received us…They could not do too much for us. They had heaps and stacks of cooked rations along our route…and the glad shouts of ‘Hurrah for our Southern boys,” greeted and welcomed us at every house.”[2]

By contrast, alarm was the prevalent attitude along the Ohio River. Confusion reigned between the cities of Louisville and Cincinnati, displaying both hysterical fear and genuine concerns about the cities’ defense.[3] While the number of Federal soldiers in the region grew rapidly, few had seen significant service. Many regiments were entirely green, raised only weeks earlier in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 300,000 volunteers. Ohio Governor David Tod assessed that the Northern forces in the region, “both officers and men, are extremely raw.”[4]

There were widespread doubts as to whether these inexperienced troops could successfully confront Bragg’s veterans. These concerns were soon validated. On August 29-30, a scratch Federal force under Maj. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson was decisively crushed by an equal-sized army of Confederate veterans under Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith at the battle of Richmond. Nearly the entire Federal force of over 6,000 troops was killed, wounded or captured, with the remaining survivors retreating in disarray.

The need for experienced troops was acute. The day after the Richmond disaster, Brig. Gen. Jeremiah Boyle, the military governor of Kentucky and commander at Louisville, shared his concerns by telegraph directly with Washington. To President Lincoln, a political and personal acquaintance, he implored that they “must have help of drilled troops unless you intend to turn us over to the devil and his imps,” further expressing his fear to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck that “the new troops will not stand before drilled rebels.”[5] A group of leading Louisville citizens, led by Thomas Hart Clay – the son of the late Kentucky Senator Henry Clay – wired Lincoln on September 3 to express that “unless the state is re-enforced with veteran troops Kentucky will be overrun.”[6]

Veterans were not readily available. Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s experienced Army of the Ohio was shadowing Bragg’s main army, undertaking a ponderous march through Kentucky. Such reinforcements would have to come from another theater.

Major General Horatio Wright, whom Halleck had appointed to the command of the reorganized Department of the Ohio on August 19, had a particular solution in mind. As he continued to press midwestern governors for new levies, he cast an eye towards Maj. Gen. Ulysses Grant’s forces spread throughout West Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama.[7] Wright cited to Halleck the example of Richmond as evidence “that newly raised troops are not reliable, even with largely superior numbers, and I desire to suggest that a force of disciplined troops, who have seen service, be sent to this department.”[8]

Halleck confirmed to Wright on September 2 that reinforcements would be forthcoming from Grant; a single division could be spared.[9] At its core were four veteran regiments – the 2nd and 15th Missouri and the 36th and 44th Illinois – with the experience and mettle needed to help steel the new recruits. All four earned a deserved reputation for their role in the Union victory at the battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas that past March. Having only recently crossed the Mississippi River to reinforce Grant, the Trans-Mississippi veterans would soon find themselves moving rapidly further east.

Reminiscences suggest that the move towards the Ohio River was well-received. Among the 36th Illinois it was later recalled that “never was a summons to march more welcome. Tired of serving the country in camp under the shadow of Mississippi oaks, any change was hailed with delight.”[10] Contemporary accounts note that the trip was one of many lengthy travels that the footsore veterans had made since the beginning of the year. “I like that map that you sent,” wrote James Watson of the 25th Illinois, another Pea Ridge veteran whose regiment would shortly join the others in Kentucky, “it is very useful sometimes to find where we are.”[11]

Their journey to Kentucky was remarkable for its speed and distance, even for veterans used to the hard-marching campaigns of the Trans-Mississippi. The regiments broke camp on September 7 and marched to the rail depot at Corinth, Mississippi, where they departed the following morning by train for the river port of Columbus, Kentucky. “Every car was packed, and numbers climbing upon top,” the regimental historian of the 36th Illinois described, “while bayonets, protruding from doors and windows, made the car resemble huge porcupines.”[12]

Detraining in Columbus that evening and spending a wet night sleeping in buildings and sheds, they would board steamships on September 9 that traveled to Cairo, Illinois. Equipment and baggage was transferred to the railcars of the Illinois Central Railroad, during which time the savvy veterans were able to purloin some poorly attended commissary stores, “whisky, ice, eggs and commissary sugar, thoroughly mixed, circulated freely, and as a natural consequence the boys were unusually smiling and happy.”[13]

The reaction among Northern civilians along the route was electric. When the trains reached Seymour, Indiana on September 10, “tables were already spread and laden with all the delicacies as well as substantials which the country afforded, to which the soldiers were heartily welcomed.” The boisterous reception carried on throughout Indiana and Ohio. “Their progress from Vincennes to Cincinnati was a continuous ovation,” and veterans described that, “roads were lined and the stations thronged with enthusiastic and excited multitudes.”[14]

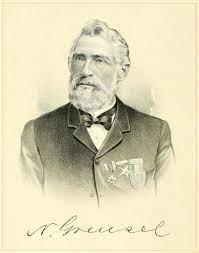

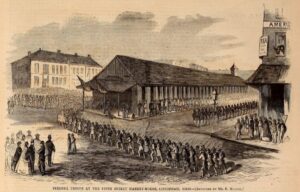

The first train arrived in Cincinnati two hours after midnight on September 11, to little fanfare and reception. The veterans were forced to spend several hours dawdling on the sidewalk until Col. Nicholas Greusel, their esteemed brigade commander, delivered a sharp parade ground drill that emphatically announced their arrival. A joyful and appreciative citizenry sprung into action. Anticipating their arrival, a banquet was prepared at the City Market Hall, with tables “loaded with viands as toothsome as manna, and presided over by little less than a brigade of ladies, the beauty and worth of Cincinnati.”[15]

The soldiers were deeply appreciative of this rapturous reception after a year of hard campaigning. Many were German-Americans, which made them particularly celebrated in Cincinnati, which boasted one of the largest German immigrant communities in the country. An unnamed soldier of the 44th Illinois, writing to the readers of the Illinois Staats-Zeitung, shared “how agreeable it is for a soldier from the army in Missouri to come out of enemy country after one year into a land of friends. What an affectionate reception we received. What jubilation along the road!” The same correspondent noted that as “these well-meaning mothers heard there would be even more regiments of old soldiers, nothing but Pea Ridgers, they did not remain there…There was cooking and baking to do for those still to come. ‘You fought with Sigel at Pea Ridge?’ was the question asked a hundred times.”[16]

The presence of these veteran regiments was a powerful tonic to the morale of the anxious citizenry. The chronicle of the 36th Illinois declared, “Never was there such a revulsion of feeling from despondency to confidence, as was experienced by the citizens of Cincinnati on the arrival of the ‘Pea Ridge Brigade’.”[17] Contemporary accounts affirm this recollection. “These are Pea Ridge veterans,” noted the Fremont, Ohio Weekly Journal at the time, “and in marching through Cincinnati pointed to their bullet-pierced flag, and cheered when they heard the rebels were only seven miles from the river.”[18] The Cincinnati Daily Commercial reassured its readers that “these regiments formed part of Gen. Sigel’s division at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, last spring – and there, by their cool, determined valor, steadiness under fire, and great powers of endurance…have won world-wide encomiums.”[19]

The regiments had traveled nearly 600 miles – by foot, river and rail – in a mere five days. They were soon joined by another four regiments of Pea Ridge veterans at Louisville, who were attached to Buell’s army a couple of weeks prior and endured a grueling march from Florence, Alabama, arriving “without shoes, ragged and dirty…contrasting beautifully with the nearly uniformed recruits about the city.”[20]

The arrival of the Pea Ridge veterans, as Halleck surmised, would successfully “give confidence to the new levies.”[21] They certainly made a strong impression. “Such jaded men!” exclaimed a recruit in the 21st Wisconsin to his parents, “The pleasure of a bath I am sure they have not known these weary months.”[22] The veterans recalled that the “first day or two after leaving the city these green soldiers looked upon the war-worn veterans as dirty, lousy fellows,” but after several days of hard field service, “they looked upon the old regiments with some degree of reverence and a considerable amount of awe.”[23]

Buell would use the Pea Ridge veterans as the backbone of two new divisions, blending veteran and inexperienced troops together to improve their efficiency. For this new task, he was well served by Maj. Gen. Wright’s initiative. Telegraphing Halleck on September 12, he bemoaned that “we have no good generals here and are badly in want of them.” Wright had a solution in mind. “Sheridan is worth his weight in gold,” Wright suggested, eyeing the young regular army officer, who was well-known to Halleck from his staff in Missouri, “Will you not try to have him made a brigadier at once? It will put us in good shape.”[24] It was done the following day, and a newly minted Brig. Gen. Phillip Sheridan took his first step into the front rank of the Federal pantheon.

Sheridan and the other soldiers of the Trans-Mississippi cohort would serve in Buell’s army at the battle of Perryville. Thereafter, they lost much of their distinctiveness amid an army of experienced troops. They instead became charter members of another esteemed military family, the soon-to-be-anointed Army of the Cumberland. with which many would serve until the closing days of the war. Yet even after many campaigns and decades later, these Pea Ridge veterans still recalled with great fondness the exciting days when they were the deliverers of Cincinnati, Louisville and the Union.

Endnotes:

[1] E.J. Ellis, October 2, 1862, Ellis and Family Papers, LSU.

[2] Sam Watkins. Company Aytch: Or a Side Show of the Big Show. (New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc., 1999), 42.

[3] Kenneth Noe. Perryville: This Grand Havoc of Battle. (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 82-84.

[4] The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 16, Part 2, 511.

[5] OR, Series 1, Vol. 16, Part 2, 465-466.

[6] OR, Series 1, Vol. 16, Part 2, 479.

[7] OR, Series 1, Vol. 16, Part 2, 459, 475.

[8] OR, Series 1, Vol. 16, Part 2, 472.

[9] OR, Series 1, Vol. 16, Part 2, 472.

[10] Lyman G. Bennett and William F. Haigh. History of the Thirty-sixth regiment Illinois volunteers during the war of the rebellion. (Aurora, Ill., Knickerbocker & Hodder, 1876), 227.

[11] James G. Watson. “James Watson’s Letters: Journey to War and Back”. (National Park Service) October 16, 1862. Accessed from: https://www.nps.gov/stri/learn/historyculture/upload/Watson_James_G_Middleton_Journey_Trnascription_508.pdf.

[12] Bennett and Haigh, 227-228.

[13] Ibid, 229.

[14] Ibid, 280.

[15] Ibid, 281.

[16] Illinois Staats-Zeitung, September 16, 1862. Translation accessed from: https://82ndillinoisinfantry.yolasite.com/44th-illinois-letters.php.

[17] Ibid, 282.

[18] Fremont (OH) Weekly Journal, September 19, 1862.

[19] Cincinnati Daily Commercial, September 18, 1862.

[20] David Lathrop. History of the Fifty-ninth regiment Illinois volunteers. (Indianapolis: Hall & Hutchinson, 1865), 155.

[21] OR, Series 1, Vol. 16, Part 1, 6.

[22] Mead Holmes. Soldier of the Cumberland: Memoir of Mead Holmes, Jr., Sergeant of Company K, 21st Wisconsin Volunteers. (Boston: American Tract Society, 1864), 87.

[23] Lathrop, 163.

[24] OR, Series 1, Vol. 16, Part 2, 510.