The Downfall of a Federal Corps Commander: Warren-Sheridan and the Five Forks Controversy: Part Two

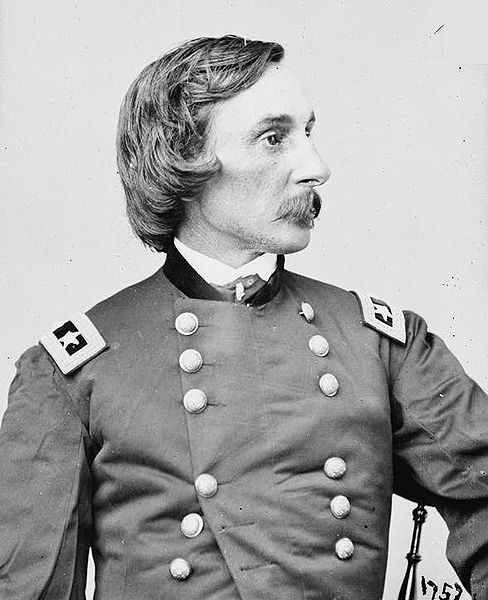

It was actually an amazing feat that Gouverneur K. Warren still retained a corps command at the start of 1865. His wartime record was solid, but far from stellar. As I mentioned earlier, Warren was an odd duck. His wartime photographs show a confident and somewhat dashing officer. Upon closer examination, the pictures of the time reveal a beady eyed man, dripping with a combination of confidence, and arrogance. There is no doubt that Warren was cocksure of his abilities. Warren had a brilliant mind for mathematics, cartography, and tactics. These traits allowed him to excel in the classroom and on a number of battlefields. Though there were underlying problems. Like many book-smart people, Warren at times lacked both tact and social graces. He also carried himself as if he was always right, no matter what the situation. He was essentially the smartest person in any room, just ask him. Combining all of these traits with his youth made for volatile situation’s between he and other officers.

By my estimation, G. K. Warren became too big for his britches right about the time of the Chancellorsville Campaign. While he took his duties as the Chief Topographical Engineer of the army seriously, he also showed his first real bouts of self-indulgent blathering to higher ranking officers, while also showing a propensity for being a know it all.

During the Second Fredericksburg phase of the Chancellorsville Campaign, Warren was dispatched to hurry along John Sedgwick, who was commanding the Left Wing of the army. Sedgwick was preparing to push west towards the main army, which was near the Chancellorsville Crossroads, when the 33 year old Warren arrived on the scene, and made a general nuisance of himself. John Sedgwick was many things, but quick, he was not. This did not sit well with the obnoxious junior officer playing back seat driver. Warren reported to Joe Hooker that, “General Sedgwick would not have moved at all but for his [Warren’s] presence, and that when he did move, it was not with sufficient confidence or ability.” This was totally unfair to Sedgwick while also being patently false. Sedgwick was massing for a major assault on the Confederate lines, which resulted in not one, but two battles on May 3rd, 1863.

Warren’s report of the Battle of Chancellorsville sheds some light on the man himself. The report as a whole is fully 12 pages long. Extraordinarily long for a battle report, which often are less than 3 or 4 pages, at best! In the report, Warren looked to make the report both “easily understood and interesting….” He pontificates about the fighting prowess of each army; “We should not wonder that such battles often terminated from mutual exhaustion of both contending forces, but rather that in all these struggles of Americans against Americans no panic on either side gave victory to the other like that which the French, under Moreau, gained over the Austrians in the Black Forest.” He also goes on to toot his own horn about the work he had performed in the campaign, although this was not wholly uncommon.

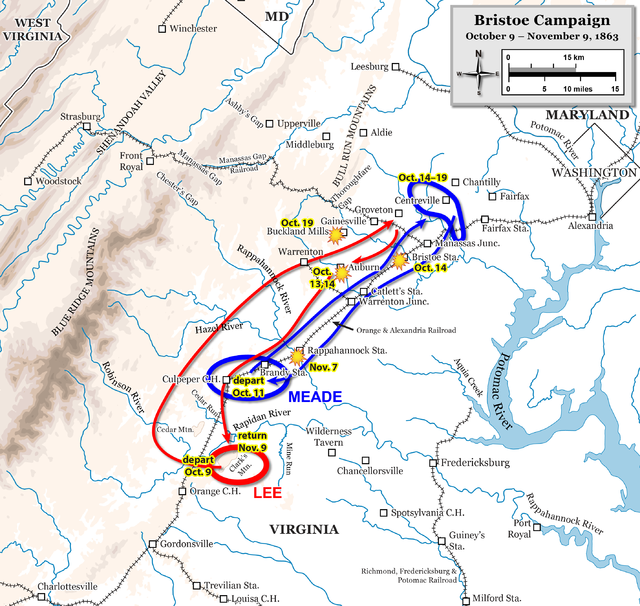

Warren’s elevation to corps command, in the late summer of 1863, brought with it an inflated sense of ego. He was then 33 and at the head of arguably Meade’s finest corps. Meade had even gone as far too shake up the command structure of the army to place Warren at the head of 2nd Corps.

After the Battle of Bristoe Station, where Warren and 2nd Corps were lauded for their “skill…..and gallantry…” Warren took it upon himself to spar with his former commanding officer, and current 5th Corps commander George Sykes. In Warren’s estimation, Sykes and his corps left Warren out to dry, and Warren felt that 2nd Corps could have been destroyed by Lee’s army. It was clear that Warren would take the fight to friend and foe alike.

A different side of Gouverneur K. Warren began to show at the time of Mine Run. As I mentioned earlier, Warren was tasked with assaulting the right of Lee’s line, with nearly one half of the Army of the Potomac. Lee had ensconced his army behind heavy earthen fortifications. Although Warren had orders from Meade to attack, he refused to move forward. Meade was incensed. Warren was the rising star in the army. The night before the attack he had argued with Meade that he should lead the attack over the senior corps leader John Sedgwick. Yet, when push came to shove, Warren would not budge (ironic since Warren had bashed Sedgwick for his supposed inactions at Second Fredericksburg).

The 3rd Corps commander, William French, who did not care for Warren, heckled Meade by saying “Where are your young Napoleon’s guns? Why doesn’t he open?” When informed by Warren’s aide, and future brother in law Washington Robeling, that Warren would not go forward into battle, Meade exclaimed, “My God! General Warren has half my army at his disposal!” Meade rode to Warren. Upon finding his subordinate Meade said, “What does this mean Gen. Warren? Why have you done this? You have ruined me.” Warren explained that “The enemy knows of our plans. I saw from a tree top that they had concentrated 40 guns on our position, and that not a man could reach them alive.”

Warren was correct in the assessment of the situation at Mine Run. In all likelihood the battle would have been a slaughter. But, Warren had shown that he could not be trusted to fully carry out an order. He should have followed proper protocol and allowed Meade to make the call, instead of making the call to cease offensive operation in the face of the enemy. This was a bad habit that reared its ugly head one more than one battlefield in 1864.

Following Mine Run, Provost Marshal Marsena Patrick felt that “…Warren has been so puffed & elated & swelled up, that his arrogance and insolence are intolerable.” The young corps commander even went so far as to write an extended 12 pages letter to his friend Humphreys telling him how he would run a campaign, and how the Army of the Potomac was being held back by certain officers.

It is clear that Warren was forthright with officers above and below him. It was also abundantly clear that his ego was becoming a problem.

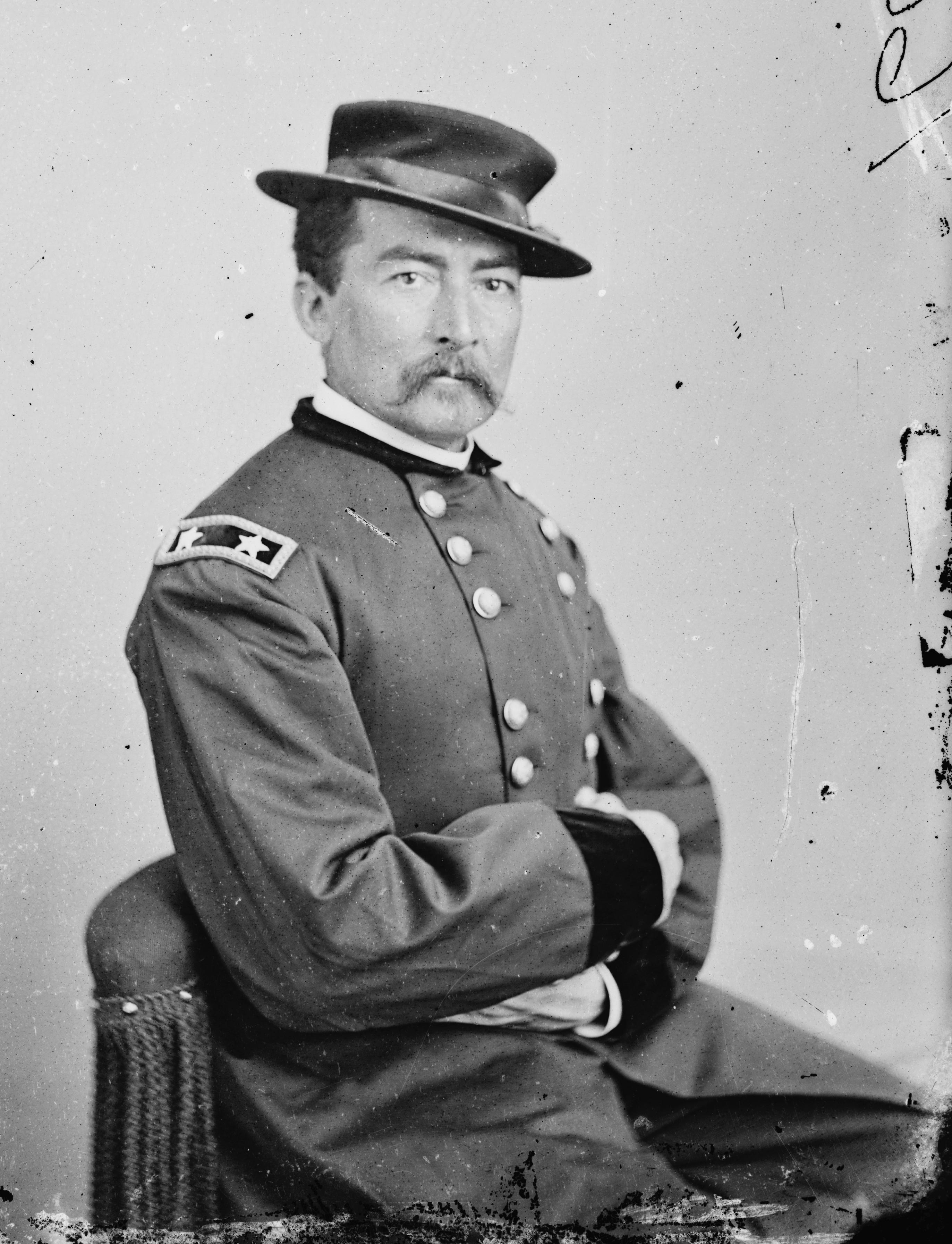

By the opening of the 1864 campaign’s Ulysses S. Grant had traveled east, bringing along with him Philip H. Sheridan, who was entrusted with the mounted wing of the Army of the Potomac. Early on Grant had seriously considered Warren “the man I would suggest to succeed Meade,” if it came to that. All of that changed on May 5th, 1864 in the Wilderness.

Warren’s corps was the first to make contact with the enemy. Wanting to impress his new boss, Meade ordered Warren forward into battle. The choking Wilderness coupled with the Federal cavalry’s failure to accurately locate the enemy weighed heavily on Meade and Warren. It took hours for Warren to shake out his corps in a line of battle and engage the enemy. In the meantime, Warren sparred via courier with Meade over his orders. By the time 5th Corps went forward the enemy was entrenched, and the assaults met with disastrous results. It was both a black eye for Warren and the army. Warren had given the impression of dragging his feet. Though he was combative with Meade he did bring up a salient point in that striking the enemy in the Wilderness was easier said than done.

At Spotsylvania, Warren had his first run in with Phil Sheridan. Sheridan’s cavalry had failed to clear the road south to Spotsylvania Court House of Confederates, and by doing so he cost the army thousands of casualties, as well as the inside track to Richmond. Warren’s corps was leading Meade’s infantry south when he was called upon to do what the cavalry could not, clear the road. Warren, like Sheridan, failed to clear the pathway of rebels and in the interim was caught in a fight between Meade and Sheridan.

For days Warren’s corps sat outside of Spotsylvania Court House, in an area known as Laurel Hill. He and his men failed to take the hill time and again. Warren’s Frustration grew. At one point he was ordered to cooperate with John Sedgwick in an assault. “I’ll be damned if I’ll cooperate with Sedgwick or anybody else,” Warren seethed in his letter back to Meade. “You are the commander of this army and can give the orders and I will obey them; or you can put Sedgwick in command and he can give the orders and I will obey them; or you can put me in command and I will give the orders and Sedgwick will obey them; but I’ll be God Damned if I will cooperate with General Sedgwick or anybody else.” Warren was known for snapping at subordinates, but his attitude toward his commanding officer was walking a thin line.

Unbeknownst to Warren he was on thin ice. During the fight for the Bloody Angle on May 12th, Warren was to make coordinating assaults with Hancock’s force attacking the Mule Shoe. Warren did not budge. He felt the position in his front was too strong. A week into the campaign Grant had had enough of the haughty New Yorker. He told Meade to send his chief-of-staff Andrew Humphreys to Warren. Perhaps an old friend could goad him into action. If he could not, Humphreys was authorized to relieve Warren and assume command of 5th Corps. In the end Warren convinced his old friend of the futility of striking the rebel line where it stood, he retained command, but it was only a matter of time before Grant’s ire turned on the once rising star.

At the outset of the Siege of Petersburg, a series of command failures in the Union Army plagued the early efforts to take the “Cockade City”. Warren was one of the culprits during the June 18th assaults. Warren seemingly could never attack on time. Meade thought that Warren had a “defect” in him. According to Meade “he cannot execute and order without modifying it…Such a defect strikes at the root of all military subordination, and it is entirely out of the question that I can command this army if each corps commander is to exercise a similar independence of action.” Meade drafted a letter to remove Warren from command, though he retracted the letter shortly thereafter.

The “defect” that Meade alludes to is something that stands out in many of Warren’s actions and letters. While I have mentioned that Warren was peevish at times, and was one to openly speak his mind, he also was quite candid in his letters home, which reveal a different side of Warren.

In one letter to his then fiancée, Emily Chase, following the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, Warren demonstrates both his confidence and need to brag :

“Oh I wish you could have seen that fight on the 27th of June when our regiment rushed against a South Carolina one that charged us. It was the opening of bitter fighting. Nothing you ever saw in the pictures of battles excelled it. The artillery which had been firing stopped on both sides, and the whole armies were spectators. In less than five minutes 140 of my men were killed or wounded and the other regiment completely destroyed.”

Other letters home show a completely different side of the general. He lamented in one letter that “happiness is not my companion…” (Which is subsequently the title of David M. Jordan’s outstanding biography on Warren.)

In another letter, written in the fall of 1863 he told Emily:

“I repine a good deal. I begin to feel myself give out in spirit. I need to rest where I could be contented. So long now my life has been one continued worry or excitement that, I am losing my elasticity and I am getting almost afraid of myself for I am apprehensive I cannot hold my position. ….Every day shows me more and more how this war is serving my old afflictions and making me lonely….here I sit alone in this great camp (or so I feel) and the memory of my dear absent friends comes over me and I am morbidly depressed.”

Warren’s personal correspondence is peppered with both boastful proclamations and long lines of his melancholy. Getting to know Warren as I have, and seeing his thoughts, and the thoughts of his contemporaries, much of the prevailing evidence points to the fact that he was possibly manic-depressive. There are descriptions of him being on very high highs, then dipping into a deep depression. Charles Wainwright, Warren’s chief of artillery, claimed that he was “more than ever convinced that he [Warren] has a screw loose, and is not quite accountable for all of his little freaks.” Perhaps these “little freaks” are the explanations for Warren snappish manner, haughty attitude, and downright loathsome personality that cost the New Yorker his beloved 5th Corps.

Reblogged this on stormylntz and stuff.